Dipping into the archive this morning, here’s a Hip Hops column I wrote in 2010, when craft beer in a can was both uncommon and subject to a good many knee-jerk reactions on the part of beer snobs. The Oskar Blues brewery wasn’t really the first craft brewer to embrace canning (in 2002), but centering its marketing on the novelty and utility of beer in cans was a “canny” strategy, indeed.

Canned beer in general dates to the 1930s, and All About Beer traces craft beer canning to 1991 and the long-forgotten Chief Oshkosh Red Lager brand out of Wisconsin. We called it “mircrobrewing” back then, but the lineage remains intact. A few other microbrewers tried cans during the 1990s, but it didn’t come to much.

Most importantly, Oskar Blues helped initiate a process that even the most reluctant capitalist (for instance, me) can grasp: economy of scale. As new craft breweries proliferated in the mid-2000s, and consumers signed on by accepting the idea of drinking IPAs, Stouts and Black Lager from cans, the demand was met through innovation and larger-scale production; canning lines got smaller and less expensive, mobile canning lines moved from brewery to brewery to fill gaps, and even the federal government chipped in by allowing the required labels for cans to be adhesive stickers rather than printed directly on the can itself.

Craft beer in cans is ubiquitous, which means we’ve arrived at the stage where the beer tastes fine, but the environmental cost of bauxite mining doesn’t.

Sun King Brewery in Indianapolis was the regional forerunner of craft canning, and my source for the 2010 column. It’s also one of the success stories of American craft brewing, possessing an incremental, no-unforced-errors business model that should be the subject of a book. Maybe some day I’ll write it. Until then, let’s consider just how much craft beer has evolved in the past decade.

—

You’ve likely never had great beer out of a can because so far, not much great beer has been put into a can. That’s changing, and fast.

-John Foyston, beer writer for The Oregonian

(Originally published in the Fall 2010 issue of Food & Dining)

Fermentation is nature’s way, brewing is mankind’s art and science, and the ultimate success of these interrelated endeavors is determined by the individual consumer reaction to the beer resting in his or her hand.

In turn, the consumer’s approval depends in large measure on the sort of container that has been designed to deliver the liquid to a set of waiting lips in a way that assures optimal freshness and quality. My own interest in beer containers admittedly is offbeat and selective, based less on scientific principle and technology and more on the attitude of the individual beer drinker, a state that reflects subconscious preferences, community psychologies and personal superstitions, all these combined into as many different forms as there are human beings to contrive and perpetuate them.

Many drinkers prefer draft beer, as dispensed into a glass or a cup. Others refer to themselves as “bottle babies,” refusing glassware and consuming beer directly from the bottle. In like fashion, millions of people drink directly from aluminum cans, simply popping the top, drinking the contents, feeling refreshed, and never thinking too much about it.

Perhaps owing to the expedience and informality of mass market bottled and canned beer, they have earned reproach from generations of radicalized beer aficionados, who have declared it utterly misguided to drink straight from a bottle or a can because from either, the aroma so integral to taste is largely undetectable.

I know. I’m one of them.

But these same enthusiasts have deemed it entirely suitable to enjoy the contents of a bottle or can if properly decanted into an appropriate glass. Moreover, sometimes the very fact of a beer being bottle conditioned, or naturally carbonated in the bottle, is exalted as ideal and preferred. Even so, apart from those with a nitro widget (Guinness, Boddington’s), generally most cans have remained objects of suspicion.

Is there a coherent basis for this attitude, or is it merely totemic?

Clay Robinson surveys this scene, and knows exactly where he stands.

“I’ve had a love affair with cans since I was a young boy,” says Robinson, the founder of Sun King Brewing Company, a 2009 microbrewery start-up in Indianapolis. “Dave Colt (Sun King’s brewer) and I both had beer can collections as kids.”

Canning has been part of Sun King’s business plan since its inception, and the brewery began releasing canned Sunlight Cream Ale and Osiris Pale Ale in the spring of 2010. Robinson’s favorable impression of cans goes beyond his boyhood collectibles, to reinforcement experienced during travels to the state where craft canning began.

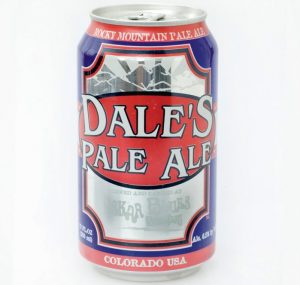

“I first had craft beer in a can six or seven years ago while visiting my sister in Colorado,” he explains. “Not surprisingly, it was Oskar Blues Dale’s Pale Ale. I remember thinking, ‘Pale Ale in a can?’ Then I bought some just to see what it was all about. I was amazed at its freshness and depth of flavor, so from that point I was hooked.”

It’s a familiar story. In craft canning circles, the Oskar Blues brewery in Lyons, Colorado, functions nowadays as a combination of Fenway Park as Mecca for Red Sox fans, Robert Johnson’s recordings as templates for blues guitarists, and the Library of Congress to document enthusiasts. In 2002, Oskar Blues became the first American microbrewery to can its ale, two units at a time to begin, and entirely by hand. The reason: Canning lines intended for small scale craft usage had yet to be produced.

Sleek and efficient smaller canning lines soon followed, thanks not only to the pioneering, niche-defining entrepreneurial efforts of Oskar Blues, but as importantly, to the active intervention of the Ball Corporation and Cask Brewing Systems.

These two far larger companies began scaling the existing canning technology to microbrewery production capacities, making it possible, albeit more expensive than bottling, to meet the demand of a restive market just awakening to the potential of canned craft beer in recyclable aluminum, which can be taken places where glass is prohibited, like beaches, outdoor preserves and sports venues.

“Save your money because it’s not cheap to get into,” is Robinson’s advice to aspiring craft beer canners, but he adds in definitive tone: “We believe that cans are a superior vessel for the transportation of craft beer.”

Robinson has a strong argument.

Aluminum itself is odorless, flavorless, pliable, lightweight and impermeable to light. Higher levels of damaging oxygen can be displaced from a can during the canning process.

According to Robinson, “The seam is a perfect seal, and the canning process functions in a cap-on-foam manner that allows for the least amount of dissolved oxygen in the finished product, and of course, light can’t get through aluminum.”

Yet acceptability still rests with the drinker. I asked Robinson how the cans have been received by the public, and his answer is emphatic.

“The response to our cans has been tremendous! We announced that we would be [canning] about six months before it actually happened, and so we spent a lot of time engaged in conversations about the virtues of cans with the people who love our beer. That, coupled with a lot of positive press for cans nationwide, has really paved the way. Plus, cans are the first time Sun King has been available in a small package.”

There is a dynamic not unlike a pendulum that keeps time during these considerations of beer packaging and containers, swinging back and forth through history as advancements are made and human cultural standards evolve. Beer has been stored inside, or been poured into, a dizzying array of man-made objects chosen from an equally wide range of materials.

Wood, stoneware, ceramic, glass, metal, and plastic; barrels, urns, vases, bottles, hogsheads, jugs and cans; and at each juncture, the objective has been the same: To maintain beer’s freshness during transport, and to see that it is consumed when freshest and best. Better ways come and go. At times, they return.

As Robinson implies, as the chosen container has become smaller, more easily reproduced and efficient, beer’s transportability has steadily been enhanced, and the experience of drinking beer inexorably removed from its point of origin in the brewery, far past a place where the brewer has control of his creation. For a brew — pub, where most house beer is enjoyed on the premises, this means less. For a brewery dependent on distribution, packaging decisions are life and death.

Impressively, for Sun King and other small craft breweries to invest in the emerging technology of micro-canning, as expressed in the currency of an aluminum container that once symbolized lesser quality beer in the minds of an earlier, more militant generation of craft consumers, is to trust resoundingly in the ongoing youthful democratization of craft beer.

The can as a container serves to widen the range of craft’s market, by taking it where it could not previously go. Micro-canning changes the game, both in terms of distribution logistics and perceptions. Beer drinkers will decant their cans into glassware when they are able, and drink straight from the can when they are not. Either way, they’ll be enjoying greater access to better beer. Let them decide.

As a romantic at heart, it is my preference to think of beer in terms both artistic and hedonistic, as liquid poetry and as metaphorical prose. Beer has been an integral part of human civilization from the very start, and its story fully justifies those flights of intoxicated fascination and smitten adoration that ensue when a few too many of the tale’s tasty chapters have been consumed in one sitting. The reality is that craft beer in cans alters none of this romance, and costs not a single intangible in return for an expansion of the perimeter.

Clay Robinson’s final thought is instructive, and brings us full circle, back to the beginning: “Regardless of the package, the beer that it carries has to be good.”

Indeed. Look for excellent canned craft beers brewed by Sun King and other trendsetters, already in stock or coming very soon, at a package store near you. F&D

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with more than 35 years of hands-on experience and expertise as a beer seller, restaurateur, and commentator. As the co-founder of New Albany’s Sportstime Pizza/Rich O’s Public House (which later became New Albanian Brewing Company) in the 1990s and early 2000s, Baylor played a seminal role in Louisville’s craft beer renaissance. Currently he is the beer director at Pints&union in New Albany. Baylor’s “Hip Hops” columns on beer-related subjects have been a fixture in F&D since 2005, and he was named the magazine’s digital editor in 2019.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with more than 35 years of hands-on experience and expertise as a beer seller, restaurateur, and commentator. As the co-founder of New Albany’s Sportstime Pizza/Rich O’s Public House (which later became New Albanian Brewing Company) in the 1990s and early 2000s, Baylor played a seminal role in Louisville’s craft beer renaissance. Currently he is the beer director at Pints&union in New Albany. Baylor’s “Hip Hops” columns on beer-related subjects have been a fixture in F&D since 2005, and he was named the magazine’s digital editor in 2019.