On Sunday we consider topics from the dusty “edibles and potables” three-ring binder, as existing outside the boundaries of our metropolitan Louisville coverage area.

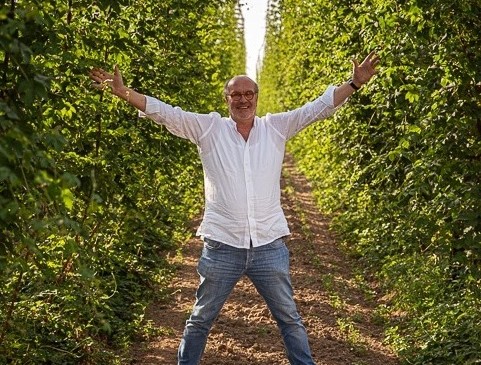

The large-scale cultivation of hops for commercial purposes tends to be concentrated in areas with specific climatic conditions: “Consistent, moderate temperature in spring, adequate moisture from irrigation or rain throughout season, and dry weather during harvest.”

Excessive heat and humidity in summer generally are deal-breakers, although nowadays progress is being made through hybridization and genetic engineering, and small-scale growers are popping up hereabouts.

In Belgium, ideal climatic conditions characterize the Westhoek (“west corner” in Dutch), a region in Flanders where hop growing is centered around the small city of Poperinge. Nearby Watou is nicknamed the “beer village” in honor of its traditional brewing prowess.

But we’re not here today to discuss hops in the context of brewing. Rather, it is to remind readers that hops can be eaten, after a fashion.

These Farmers Want You to Drink Your Hops and Eat Them Too, by Catie Joyce-Bulay (Gastro Obscura)

In Belgium’s hops-growing region of Poperinge, the tiny, tender shoots show up on menus from late February to early April. Thrown raw into salads, cooked in cream sauces, or baked, the shoots are harvested from underneath the soil and look like tiny white asparagus or bean sprouts…they are crisp and, when eaten raw, have an almost cucumber flavor.

The classic way to serve them is cooked with a poached egg and cream sauce, says Stefaan Couttenye, chef and owner of Restaurant ‘t Hommelhof in Poperinge, who has even turned them into ice cream. Couttenye says hop shoots have been found in ancient Roman cookbooks, but don’t appear to be widely used outside of Belgium.

It’s the perfect segue into an overall appreciation of beer cuisine, as pioneered in Belgium by the chef and restaurateur Couttenye at ‘t Hommelhof in Watou (he now operates a gourmet shop in Ostend, too).

It has been my good fortune to have enjoyed more than one fine meal at ‘t Hommelhof, founded more than 20 years ago by Couttenye and his wife, the late Sabine Dejonckheere. On one early springtime visit, hop shoots with poached egg and cream sauce was on the menu, and I could not resist. It wasn’t cheap; according to our guide, the price of hop shoots at the time was around $100 a pound. Otherwise the asparagus analogy is apt.

When Couttenye opened ‘t Hommelhof, the notion of beer cuisine in general, and local food sourcing in particular, remained a minority taste even in a place like Belgium. It is an understatement to suggest that he was far ahead of his time.

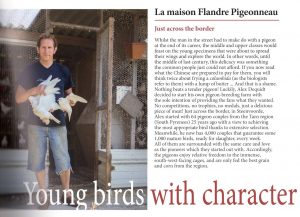

Couttenye’s 2014 book, Cooking with Belgian Beers: Great recipes flavoured with the famous ‘Westhoek’ beers, was co-written with his son Simon, who now runs the beer program at the restaurant. When it comes to local Westhoek foodstuffs, it’s best to keep an open mind, with an example being squab.

What Is Squab? (D’Artagnan)

Squab are young pigeons that have never flown. For thousands of years, they have been a favorite meal for every stratum of society throughout the world. They were unequivocally the first domesticated poultry, even preempting chicken.

This may surprise twenty-first century Americans. More often we think of pigeons as annoying denizens of city monuments and buildings. In fact, these are rock doves, a relative of pigeons, and far less edible. Yet squab is considered a most exquisite ingredient in cuisines as distinct as Cantonese, Moroccan and French. The simple reason for squab’s universal appeal is the delicate, succulent flesh, truly unlike that of any other bird. Squab is a dark-meat bird, like duck and goose, yet the meat is not nearly as fibrous, rendering it far more tender. Its flavor, when properly cooked, is a lush, rich essence, reminiscent of sautéed foie gras, albeit with more texture.

Or, “young birds with character.”

The exact details elude me, but I remember one time in Poperinge when a few of us wanted to air it out at ‘t Hommelhof. Watou is only a few miles away, but we didn’t have a way there and back for an evening of revelry. We were staying at the Hotel Palace, which at the time was owned by a wonderful couple, Guy and Beatrice.

Not only did Guy magnanimously volunteer to drive us to dinner; he also said he’d come back and fetch us later. It proved to be unnecessary, as a ride was hitched back to Poperinge with a friendly local couple who overheard us talking during the feast. They were excited about our excitement — and that’s why I return as often as possible to their “west corner” of Belgium.

(Photos in the text are from the book; featured photo is from the t’ Hommelhof page at Fb)