In 1988, I was fortunate (?) to land my first and only “real” corporate job abstracting periodicals at the now long-defunct UMI Data-Courier on 5th Street in Louisville, across the alley from Standard Gravure. I lived off my evening Scoreboard Liquors package store pay and bankrolled as much as I could to make what eventually became a six-month stay in Europe in 1989.

During my tenure at UMI Data Courier, it transpired that our British publications (The Economist, The Spectator, New Statesman, even Punch) were increasingly shunted onto my stack of work by fellow staffers after it became known that the new guy rather enjoyed reading them, and more importantly, wasn’t troubled by the English essayist’s general habit of hiding the topic sentence somewhere other than the opening paragraph.

We had quotas, you know.

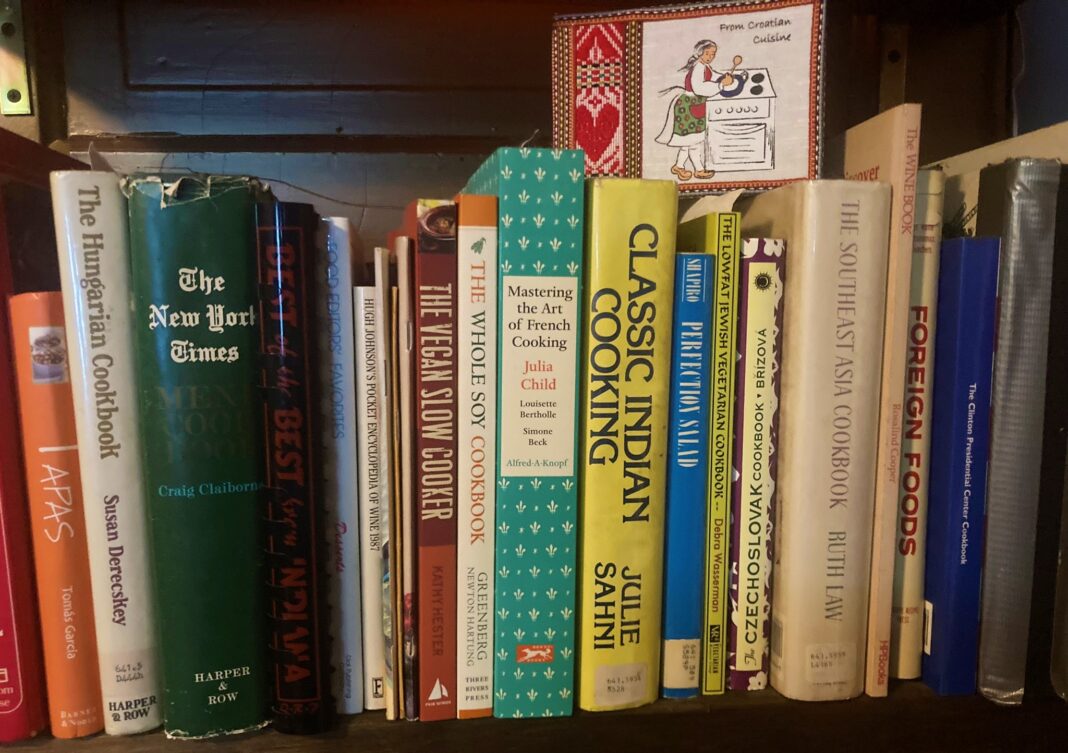

The experience greatly influenced my writing, and I’ve been subscribing to The Economist ever since. Brits call it a weekly newspaper, Americans would say “magazine,” but either way the contents include solid internationally-oriented news and analysis alongside lifestyle essays and guides like this: Our food columnist selects the seven essential cookbooks, “a tasteful tour around the cuisines of the world.”

What’s a cookbook for these days? Not just recipes: those are available online, in multiple versions, inevitably introduced by screens full of faux-chipper stories and browser-crashing pop-up ads. And not technique: again, anyone who wants to know how to clean a squid or spatchcock (a chicken) can head to YouTube. But while a single recipe or video may inform, neither can really tell a story of a person, place or cuisine. Any cookbook is only “a” story, not “the” story. Cuisines change; they bleed into each other; and they vary with each person who steps up to a stove and a chopping block. An instructional video or online recipe rarely delights, or bears revisiting just for pleasure. A good cookbook should do both. Here are the seven that most deserve a place on your shelf.

The descriptions have been truncated; visit The Economist for the full Monty.

- Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volumes I and II (1961 and 1970). By Julia Child, Louisette Bertholle and Simone Beck. Knopf; 1472 pages; $110 and £50

“Unlike her French predecessors, (Child) is an outstanding demystifier of kitchen technique, and can turn the most complex French dessert or sauce into a series of easily comprehensible steps.”

- The Silver Spoon (2005). By The Silver Spoon Kitchen. Phaidon Press; 1505 pages; $49.95 and £39.95

“If you’re used to red-sauce cooking and think Italian food begins with spaghetti, progresses to pizza and ends at lasagna, then this book, initially published by a Milanese architecture and design magazine in 1950, will surprise you with its breadth, and relative paucity of tomatoes.”

- The Food of Sichuan (2019). By Fuchsia Dunlop. W.W. Norton; 480 pages; $40 and £30

“In the West, Sichuanese cuisine has a reputation for being spicy, and it often is, but Ms Dunlop also includes the subtler dishes—the warming soups and invigoratingly sour cold dishes.”

- The Book of Jewish Food (1996). By Claudia Roden. Knopf; 688 pages; $50. Penguin; £26

“(Roden) has produced an ethnography of the world’s Jewish cultures, extant and vanished, told through food.”

- Jubilee: Recipes from Two Centuries of African American Cooking (2019). By Toni Tipton-Martin. Clarkson Potter; 320 pages; $35. Ballantine Books; £27.50

“(Tipton-Martin’s) book shows the breadth and sophistication of African-American contributions to the American table. Even American gourmets will learn as they read.”

- Made in India: Recipes from an Indian Family Kitchen (2014). By Meera Sodha. Flatiron Books; 320 pages; $35. Fig Tree; £20

“Aged 80, my grandma enjoys a bit of bingo, the occasional Bollywood film and properly slapping a millet bread about until it’s perfectly round.”

- Six Seasons: A New Way with Vegetables (2017). By Joshua McFadden. Artisan; 384 pages; $40 and £30

“It isn’t vegetarian; it just puts vegetables at the centre of the meal, and treats them not as something to eat because people must, but as something to happily prepare because, when properly grown and picked at the right time, they are delicious.”

Previously at Edibles & Potables, why I don’t consider myself to be a “foodie” as such. The essay predates a vast reduction in personal red meat and fowl consumption. Can a pescatarian be a trencherman, too? I think so, yes.