After all of these years traipsing around Europe—well, strictly speaking, I spent a few hours in Asia one day waiting for a ferry back to Istanbul, but otherwise the Europhilia is quite real—it annoys me to remain monolingual.

English is my first and only language, and although there’s no denying the efficacy of English given its undisputed status among the planet’s non-native speakers as being their most desired second tongue, I feel as if I’ve failed.

I’d have made a rotten expatriate in Trieste. Did James Joyce ever learn to speak Italian, Slovenian or Habsburg?

If given the chance for that rarest of human events, a do-over, I’d probably opt for a more sustained effort to speak at least some vaguely conversational German. As it stands, I know enough German to say hello and goodbye, count a bit, comprehend basic directions, and decipher restaurant menus and beer labels.

The latter gives rise to further reflection, because the notion of language, or those “words used in a structured and conventional way and conveyed by speech, writing, or gesture” as a shared system of communication, suggests I may be multilingual after all.

Does it count to speak Beer?

I offer “Beer” in a broad and vernacular sense, as with a regional dialect or street slang. Grammar is less a factor than passion and inflection. Speaking for myself, I lack the technical jargon and scientific background to speak Brewhouse Beer, which is like a formal academic language.

Naturally one might speak both.

A real-world linguistic example can be found in Greece, where Dimotiki (Demotic) Greek is the everyday language, while Katharevousa Greek is the formal, academic tongue. Assuming you are Greek and know both, Katharevousa isn’t the way to order food and drink at the waterfront café.

Speaking ordinary everyday Beer needn’t imply proficiency as a trained beer judge or cicerone. Rather, you’re able to look at the draft list at Pearl Street Taphouse or Holy Grale and grasp the stylistic intent and overall vibe even if you’ve never heard of the specific brewery.

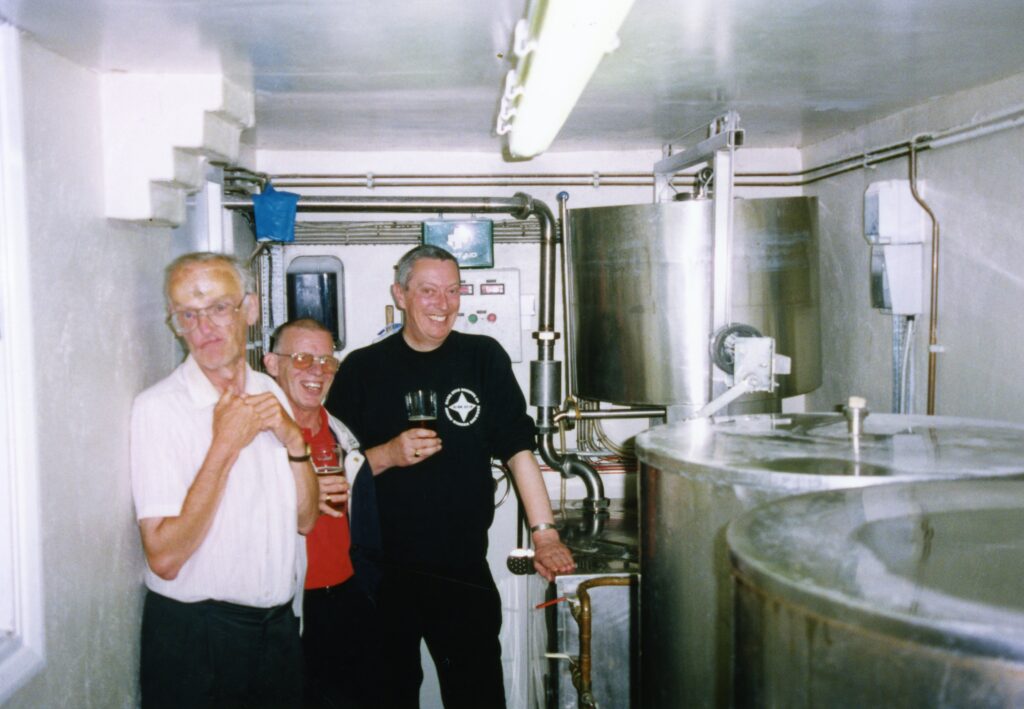

Beer-speak means being sufficiently worldly to wander into just about any on-premise bar, tavern, taproom, Gaststätte or cerveceria, anywhere in the world, and intuitively know how to get hold of a beer and a snack, and make oneself at home.

It means having a feel for the past and knowing the high points of beer history, as well as the basics of beer ingredients and processes. It’s a certain fluency in genre.

But more than anything, Beer as a language is a literal act. You must speak and write it, using real words. Furthermore—and this will shock some—you cannot resort to the kaleidoscope of beer porn images on your smart phone.

For quite some time I’ve been making the argument that the current state of beer appreciation is being cheapened, stunted, subverted, and occasionally crippled by the digital era of flash card visuals.

Beer hoarding, collecting, list making and various other forms of misplaced me-first fetishism are also taking their toll, but advancing one’s beer advocacy by sole use of photographs, as opposed to words, strikes me as a tacit embrace of illiteracy.

And: I worked too damn hard to become literate, whether in Beer or English, to tolerate the regression. Call me a Luddite, but I’m taking a stand for first causes and storytelling.

A noted Irish poet once said, “I’m just trying to find a decent melody, a song that I can sing in my own company.”

Conversely, I’m always searching for just such a beer, all tactile and real-world, echoing Michael “Beer Hunter” Jackson’s timeless observation that the pursuit of the perfect pint should last a lifetime, and if you ever find one, which isn’t the point, there’d be no way of photographing this ideal beer or reducing it to a numerical score. Spiritual matters defy easy categorization.

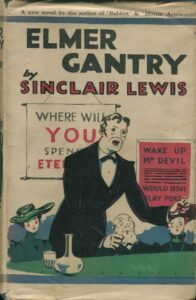

Music and literature always help calm the savage bile-ridden breast. There’s a pleasant Mendelssohn string quintet playing as I write these words in both Beer and English, and following is an excerpt from Elmer Gantry, a classic satirical novel.

Elmer Gantry, the traveling evangelist who loved whiskey, women and wealth, was conceived by Sinclair Lewis in a best-selling 1927 novel. Lewis went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, and Gantry went on to lofty-synonym status: Displays of hypocrisy and showmanship will often evoke his name, especially in reference to preachers — and, increasingly so, to politicians.

In this immortal passage, the garrulous charlatan Gantry converses with the humble true believer, Pastor Pengilly—and it happens in Indiana, of all places.

Even a pagan like me is capable of spotting the topic sentence, which I’ve highlighted in bold and provided with alternate wording.

—

(Gantry) came with a boom and a flash to the town of Blackfoot Creek, Indiana, and there the local committee permitted the Methodist minister, one Andrew Pengilly, to entertain his renowned brother priest…when he heard that the Reverend Elmer Gantry was coming, Mr. Pengilly murmured to the local committee that it would be a pleasure to put up Mr. Gantry and save him from the scurfy village hotel.

(Gantry) came with a boom and a flash to the town of Blackfoot Creek, Indiana, and there the local committee permitted the Methodist minister, one Andrew Pengilly, to entertain his renowned brother priest…when he heard that the Reverend Elmer Gantry was coming, Mr. Pengilly murmured to the local committee that it would be a pleasure to put up Mr. Gantry and save him from the scurfy village hotel.

He had read of Mr. Gantry as an impressive orator, a courageous fighter against Sin. Mr. Pengilly sighed. Himself, somehow, he had never been able to find so very much Sin about. His fault. A silly old dreamer. He rejoiced that he, the mousy village curé, was about to have here, glorifying his cottage, a St. Michael in dazzling armor.

After the evening Chautauqua Elmer sat in Mr. Pengilly’s hovel, and he was graciously condescending.

“You say, Brother Pengilly, that you’ve heard of our work at Wellspring? But do we get so near the hearts of the weak and unfortunate as you here? Oh, no; sometimes I think that my first pastorate, in a town smaller than this, was in many ways more blessed than our tremendous to-do in the great city. And what IS accomplished there is no credit to me. I have such splendid, such touchingly loyal assistants — Mr. Webster, the assistant pastor — such a consecrated worker, and yet right on the job — and Mr. Wink, and Miss Weezeger, the deaconess, and DEAR Miss Bundle, the secretary — SUCH a faithful soul, SO industrious. Oh, yes, I am singularly blessed! But, uh, but — Given these people, who really do the work, we’ve been able to put over some pretty good things — with God’s leading. Why, say, we’ve started the only class in show-window dressing in any church in the United States — and I should suppose England and France! We’ve already seen the most wonderful results, not only in raising the salary of several of the fine young men in our church, but in increasing business throughout the city and improving the appearance of show-windows, and you know how much that adds to the beauty of the down-town streets! And the crowds do seem to be increasing steadily. We had over eleven hundred present on my last Sunday evening in Zenith, and that in summer! And during the season we often have nearly eighteen hundred, in an auditorium that’s only supposed to seat sixteen hundred! And with all modesty — it’s not my doing but the methods we’re working up — I think I may say that every man, woman, and child goes away happy and yet with a message to sustain ’em through the week. You see — oh, of course I give ’em the straight old-time gospel in my sermon — I’m not the least bit afraid of talking right up to ’em and reminding them of the awful consequences of sin and ignorance and spiritual sloth. Yes, sir! No blinking the horrors of the old-time proven Hell, not in any church I’M running! But also we make ’em get together, and their pastor is just one of their own chums, and we sing cheerful, comforting songs, and do they like it? Say! It shows up in the collections!”

“Mr. Gantry,” said Andrew Pengilly, “why don’t you believe in God/Beer?”

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 40 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 40 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.