It has been 33 years since my first visit to the country then known as Czechoslovakia. There were many more stays to follow, and a consistent theme dominates the narrative.

Yes, it’s beer.

Škodas have their merits as conveyance, and I genuinely adore Smetana’s and Dvořák’s music, but let’s keep the focus on liquidity.

To understand what it was like for a beer drinker to be traveling in a place like Czechoslovakia in the 1980s, we must begin by forgetting almost everything we’ve learned during our contemporary “craft” beer era.

Prior to the arrival of the pandemic in 2020, there were more than 8,000 operational breweries in the United States. In 1987, approximately 150 were in existence in America. That’s all. Roughly half of them had come into existence during the preceding decade.

It isn’t a misprint. When I started college in 1978, there weren’t 100 breweries in our whole country. Conversely, in 1987 there were around 70 breweries in Czechoslovakia, at the time a country of a mere 15,000,000 inhabitants, as opposed to 242,000,000 in America. The per capita rate of beer consumption was far higher in Czechoslovakia than in the USA, especially in the Czech lands of Bohemia and Moravia, although not as much in Slovakia, which later became independent, thus rendering the Czech Republic’s statistical consumption to an even higher level.

Just as much as in Germany, beer and brewing culture were omnipresent in Czechoslovakia, although comparatively limited in terms of stylistic diversity. On the other hand, back then we’d yet to be conditioned to expect dozens of styles from which to choose whenever going out for a pint.

In Belgium, maybe, but in Czechoslovakia, one made do and happily endured numerous hop-accented golden variations on a theme of Pilsner Urquell. Notably, no other Czechoslovak brand referred to itself as a “Pilsner” – this honor and appellation was reserved for the Plzeň-brewed original – and yet the majority were similar, brewed to varying strengths in the 4% to 6% abv range, albeit referred to confusingly (to our eyes) by degrees of original gravity prior to fermentation. 12 degrees worked out to 5% or thereabouts.

The British traveler and beer writer Ronald Pattinson explains a key point.

In 1988 many Czech breweries were almost unchanged from the 1930’s. While productivity may have been low, there was no argument about the quality of the beers brewed. Open fermenters, long lagering times and absence of pasteurisation produced distinctive and flavoursome beers. No other country came even vaguely close to the general high standard of Czech lager. It was impossible to find bad beer.

The larger regional breweries – Staropramen, Gambrinus, Velké Popovice and, of course, Pilsner Urquell – had national distribution. Even in a town like Prague, where there were several large local breweries, there was a good choice of beer from the whole of Czechoslovakia.

There also were a few dark lagers, which tended to be of lower gravity, and exhibiting a pronounced malty sweetness, as well as the occasional “black” lager of better balance and increased potency. Even an old-fashioned, bottom-fermented porter might pop up out of nowhere to surprise you.

Still, drinking beer in Czechoslovakia in 1987 usually meant sampling the same basic style brewed by different breweries. The fun part was roaming cities like Prague in search of the pub on the back street that served one you hadn’t seen previously.

My friend and travel mate Barrie and I dropped into several of the more famous Prague taverns during our brief stay in 1987: U Dvou Koček, U Pinkasů and U Fleků among them. The latter was (and remains) a brewery, and in case you were wondering, it helps to know that in Czech, “U” means “at” and often is incorporated as a sort of metaphysical prefix to the pub’s name.

Communism was all about investing in selected economic goals, and disinvesting in others. As Pattinson observes, this actually had the curious effect of helping to maintain overall beer quality in Czechoslovakia, in the sense that in the absence of abundant capital for modernization, the older and slower ways persisted.

“Old school” wasn’t a beer cliché. It was every damn day.

As economics pertained to taverns and watering holes, it was a mixed bag. Even the venerable beer shrines reflected the realities of their time, and some were in better repair than others. In most cases, you’d find an abundance of wood, plaster and cigarette smoke. The vibe tended to be relaxed and quiet, and inexpensive beer prices were somewhat uniform everywhere you went.

Granted, waiters were notoriously prone to padding checks with hidden cover charges, but the prices were so low you seldom noticed – and as noted above, the beer was unfailingly wonderful.

If I’m to be honest about our time in Prague in July, 1987, it’s highly doubtful we dropped into the drinking establishment that subsequently became a great personal favorite of mine, the Automat Koruna (1931 – 1990s). However, after three weeks in Prague in 1989, the workers there probably knew me by sight, if not by name.

Prague’s famous Wenceslas Square (Václavské náměstí) was the city’s original horse market, and it isn’t a square at all. It’s a rectangular boulevard, originating atop a gentle rise in front of the Czech National Museum, then descending to where the Old Town begins. At this intersection (Václavské náměstí 1), just a few feet from the subway stop, is a sizable Art Nouveau building called the Koruna Palace, which opened in 1914.

Photo credit: Koruna Palace

Strictly speaking, an “automat” is a vending machine. The first such automat for food and drink was introduced in Berlin in 1895. From what I can tell, the Automat Koruna followed suit from its inception in 1931, though the Koruna Palace was such a large building that there were other food service businesses situated inside it. It’s never been clear to me where originally one of them ended, and the next began.

Whatever the ultimate disposition of the vending machines and the date of their removal, by the time I experienced the Automat Koruna (sometimes referred to as the Buffet Koruna), it was a high volume, self-service, cafeteria-style eatery with multiple counters, where customers could buy nibbles, full meals, sweets, coffee and the Koruna’s famous strawberry milkshakes.

Or, in Czech, a jídelna — a canteen, cafeteria or snack bar.

The most famous jídelna was Automat Koruna, opened in 1931 in the Koruna Palace, on Wenceslas Square — it was even frequented by President Antonín Zápotocký. The spot served a whopping 5,000 chlebíčky (open-faced sandwiches) and 1,800 liters of beer daily. Eating Prague tour guide Eva Brejlová remembers how busy jídelny would get in the 1980s. “If you left your sausage for even just a moment, someone would be there asking if it was free,” she says. Automat Koruna shut down in the 1990s in the shadow of fast-food franchises like McDonald’s, but there has been talk of reopening it.

Indeed, it’s a model still popular to this day. It’s the “egality” of the jídelna that “speaks so powerfully” to Czechs, according to Honza Valenta of food tours company the Taste of Prague. “It doesn’t matter who you are outside of the jídelna, you get the same food, same drinks and same treatment as everybody else. And we, just like the rest of Central and Eastern Europe, kinda like that.”

In case you’re wondering, 1,800 liters works out to 30 standard half-barrel American kegs.

A day.

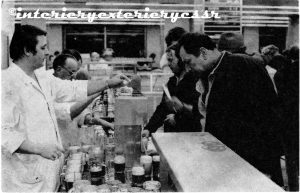

You told the cashier what you wanted, paid, and were handed a receipt. Then came a sociable wait in the customarily long line, enough to be amazed by the perpetual motion of the white-smocked beer men, who’d constantly have a couple dozen foamy beers waiting to be topped off to the half-liter pour line. Eventually one of them took the ticket and slid a cool, golden mug across the counter.

It was Pražan beer, brewed a few miles away in Holešovice district of Prague. I’d say Pražan was comparable to Pabst Blue Ribbon in pre-hipster days of yore in the sense of being a blue-collar lager, but we must recall that in theory there were no such distinctions in a communist country.

It was Pražan beer, brewed a few miles away in Holešovice district of Prague. I’d say Pražan was comparable to Pabst Blue Ribbon in pre-hipster days of yore in the sense of being a blue-collar lager, but we must recall that in theory there were no such distinctions in a communist country.

Wink wink, nudge nudge.

You consumed your Pražan and also dined while standing at a stainless steel table. There may have been chairs at the Automat Koruna, but if so, I can’t remember ever seeing them; at any rate, I never sat. Crowds were a constant, and stand-up space sometimes at a premium.

The ambiance at Automat Koruna was urban, frenetic and often claustrophobic – but I loved it, and what a place to drink beer and people-watch! The clientele reflected an indisputably egalitarian ideal, although for communism’s usual litany of wrong reasons.

Military men with medal-filled chests jostled for space with long-haired students. Backpacking tourists and shop clerks with fashion model looks stood side by side. Brown-suited functionaries left scraps on their plates, and people obviously down on their luck, even in the worker’s paradise, scooped them up before the workers came to tidy up. It was ill-advised to step away from your beer, because they’d drain unguarded remnants in milliseconds.

In closing, it’s worth noting that these perfectly presentable half-liter local draft beers were three to a dollar.

Cheap beer hasn’t ever been this good, or more indicative of real life in real time.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with more than 35 years of hands-on experience and expertise as a beer seller, restaurateur, and commentator. As the co-founder of New Albany’s Sportstime Pizza/Rich O’s Public House (which later became New Albanian Brewing Company) in the 1990s and early 2000s, Baylor played a seminal role in Louisville’s craft beer renaissance. Currently he is the beer director at Pints&union in New Albany. Baylor’s “Hip Hops” columns on beer-related subjects have been a fixture in F&D since 2005, and he was named the magazine’s digital editor in 2019.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with more than 35 years of hands-on experience and expertise as a beer seller, restaurateur, and commentator. As the co-founder of New Albany’s Sportstime Pizza/Rich O’s Public House (which later became New Albanian Brewing Company) in the 1990s and early 2000s, Baylor played a seminal role in Louisville’s craft beer renaissance. Currently he is the beer director at Pints&union in New Albany. Baylor’s “Hip Hops” columns on beer-related subjects have been a fixture in F&D since 2005, and he was named the magazine’s digital editor in 2019.