“The term ‘NULU’ is a portmanteau meaning ‘New Louisville’. As home to the greenest commercial building in Kentucky, many historic restoration projects, as well as several restaurants offering organic and locally sourced ingredients, NULU has emerged with a culture of sustainability.”

“The term ‘NULU’ is a portmanteau meaning ‘New Louisville’. As home to the greenest commercial building in Kentucky, many historic restoration projects, as well as several restaurants offering organic and locally sourced ingredients, NULU has emerged with a culture of sustainability.”

Kudos to the NULU Neighborhood Association, because after two years in the COVID-19 deep freeze (see “Eisbock” below), NULU Bock Fest is returning on Saturday, March 26 from 12 noon to 6:00 p.m., to unfold in the 600 and 700 blocks of East Market Street.

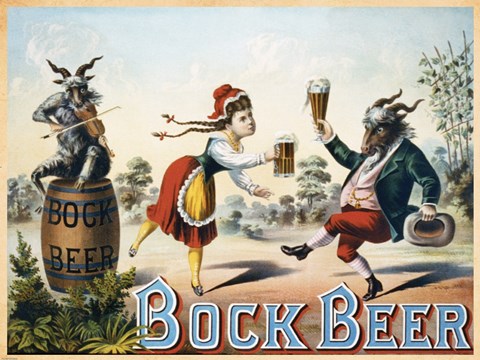

NULU Bock Fest is the modern reanimation of a springtime festival tradition dating to 19th-century German-American communities across the United States, rather like St. Patrick’s Day among Irish immigrants, but unlike the Hibernian fete, destined to fall out of favor following the twin whammies of the Great War and Prohibition.

Here’s the prospectus, courtesy of an information release.

NULU’s Bock Fest returns in person after two years off with safe and fun goat racing, local Bock Beer, and the annual Wurst Fest. This year will welcome several local breweries including Akasha Brewing Co., Against The Grain, Falls City Beer, Goodwood, Gravely Brewing, Mile Wide Brewing, Monnik Beer Co., West Sixth Brewing, and Ten20 Craft Brewery with more to be announced. Each brewery will serve its 2022 Bock Beer, along with other selections, at the event. Beer is available for purchase at booths along the 600 and 700 blocks of East Market Street.

Goat racing is a nice touch, indeed.

Goat races are traditionally associated with Bock Day, as “bock” means “goat” in German. The event will kick off with the ceremonial blessing of the goats at Noon, and the day will include seven races with separate divisions for kids (baby goats) and adults. The goats will race from Nanny Goat Strut Alley to Billy Goat Strut Alley on Clay Street.

There’ll be many activities at NULU Bock Fest, but for the sake of today’s teaser, let’s stick to the liquid side of the ledger, which I covered at some length just last year.

Hip Hops: The back story of Bock, because the time draws near

The basics of Bock in the context of Bavarian tradition, which to a large degree made the passage to America, come down to color, strength and season. Bock tends to be dark, stronger than everyday beer, and associated with late winter and early spring. There are exceptions, of course, and yet to know just this is sufficient to appreciate the style and occasion. From the preceding link to the 2021 essay:

As the final cold gusts of winter recede, and spring’s stirrings draw tantalizingly near, it is time for Bock: A rich, deep, chestnut-colored lager of higher than average strength, served in impossibly huge steins, designed to lure the timid from dens of placid hibernation beside fiery hearths, and back out into chilly outdoors beer gardens, all the better to prepare for days growing steadily longer and a new planting season just around the corner.

Delving slightly deeper, following are the stylistic variants, as based on the Beer Judge Certification Program parameters with the usual disclaimer: style is a negotiation and lasts a lifetime, just like one’s pursuit of the perfect pint.

Helles Bock (or Maibock): Strong, malty and usually tawny golden. Maybe it’s a beefed-up “Helles” (pale), or conversely a paler shade of “Dunkles” (dark) Bock. As the word “Mai” (May) suggests, Helles is often considered seasonal to late spring, but nowadays, who knows?

Dunkles Bock: “Dunkles” means dark, and for me this modifier is redundant, because darkness is understood, and Bock is dark unless it is additionally modified as Helles.

Doppelbock: “Doppel” means double, and while this is not to imply double the customary strength – think of it as a marketing term – Doppelbock traditionally were among the stronger lagers a Bavarian brewery produced. Munich’s “Starkbierzeit” (strong beer time) is the occasion for Doppelbock consumption.

Eisbock: “Eis” means ice, and quite literally the finished beer is frozen and the water removed, which concentrates the alcohol content as well as the Bock flavors and aromas.

Weizenbock: “Weizen” means wheat, and this is a wheat-based ale with certain Bock characteristics. Both dark and pale varieties exist, and in both you’ll find the enhanced presence of signifying Weizen esters (fruity flavors, like bananas) and phenols (clove-like spiciness).

Finally, another excerpt, this time from local writer Kevin Gibson, who tells one of the best Bock tales in his book, Louisville Beer: Derby City History on Draft. It recounts the pre-Prohibition Louisville institution of Bock Day, which was a much anticipated springtime revel.

Henry Caldwell and Mary Smith were drinking on March 18, 1894. The couple apparently enjoyed several bock beers that day, according to a police account, and decided to make a living, breathing bock beer sign to celebrate their enthusiasm for Bock Day. However, as they couldn’t find a goat, they instead stole a pig and apparently tried to paint the poor animal into a sign near the corner of Ninth and Walnut Streets.

“The beast objected loudly,” according to the report, “and disturbed the services of the church near by. Officers McPeak and Hessian arrested all three. The pig was sent to the West End pound, and the man and woman to the station house. They told different stories about how they came into possession of the pig.” One wonders if the police officers themselves had hoisted a few bocks that day, given that they arrested a pig.

But these sorts of stories were common finds in my research into Bock Day in Louisville. From mudball fights to broken windows and hatchet attacks, it seems that the long winter of drinking lighter beers and lingering indoors left many Louisvillians unprepared for the punch in the brain that the bock brought with it.

Let’s hope that hastily drafted porcine imposters do not factor into NULU Bock Fest in 2022, although greased hogs might well preface the run-up to Oktoberfest.

Reed Johnson, are you listening?