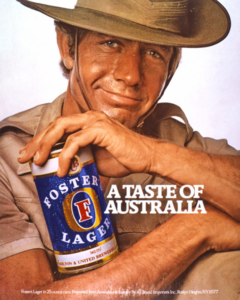

During the Stoned Age, when Crocodile Dundee and Outback Steakhouse roamed the earth with impunity (and nary a sliver of ironic detachment), so did a beer called Foster’s Lager.

During the Stoned Age, when Crocodile Dundee and Outback Steakhouse roamed the earth with impunity (and nary a sliver of ironic detachment), so did a beer called Foster’s Lager.

Foster’s Lager was created in 1887 at a brewery in Melbourne built by two Americans (but of course my countrymen were responsible) and it became available in America in 1972, as packaged in 750 ml heavy metal “oil” cans fabricated at the same plant where smokestacks for WWI dreadnoughts were turned out.

These oversized cans were considered the epitome of macho by any junior high school boy in Keokuk who could actually manage to lift one.

(Meanwhile, in Floyds Knobs, I managed; then again, those were the daze of my adolescent athletic pursuits — may they rest in peace.)

Australia was an exotic and elusive concept during Jimmy Carter’s presidency, but we had Foster’s Lager and AC-DC, often both at once, the combination of which occasionally produced hallucinations of Vegemite and kangaroos.

Consequently I learned a lot in 1985, when a well-traveled but still quite youthful Australian fellow named Mark Douglas took me under his wing during a brief group trip stay in Leningrad (St. Petersburg), USSR.

Mark learned that it was my birthday, vowing to find an appropriate eatery to host a typical Russian celebration. His choice was the excellent Baku Restaurant, and I was grateful for the food and drink; unfortunately, Mark missed much of the evening, having mistakenly imagining that Aussies are the equals of Russians when it comes to consuming vodka neat.

Then as now, attitudes like this can lead to heartache (and vague nausea).

Mark might have fared better had he stuck with mass consumption of beer, but the better Soviet restaurants seldom stocked it, and the price my new friend from Oz had negotiated for entry with the doorman (circa $20 cash for two persons) included not only all we could eat, but also unlimited vodka and champagne, as opposed to mere pivo.

The overarching point: I distinctly recall quizzing Mark about Foster’s Lager, and being told in no uncertain terms that just because unschooled Americans drink sh—y beer, don’t go imagining his countrymen would follow suit.

He must have been a Toohey’s man.

By the time I returned to Europe in 1987, Foster’s Lager in America remained a fast-selling “imported” beer, which is not to say that it was brewed in Australia. That’s because one of the enduring charms of a planetary economy controlled by multinational corporate robots is never having to open a dictionary so long as you’re properly capitalized.

As such, the marketing phrase “Foster’s is Australian for beer” actually was pronounced “Foster’s welcomes you to Ontario.”

Alas, the dreadnought smokestack factory Down Under had shuttered, and the oil cans were transformed into svelte aluminum, absent their previous rough-edged panache — and it made absolutely no difference to me because at this point I was drinking German, British or Belgian beers as actually brewed in those countries whenever I could afford the splurge, and if money was tight, there was always the Hudepohl-Schoenling iteration of Christian Moerlein, which was unexpectedly good.

Around this time I was working at Scoreboard Liquors in New Albany, and distinctly recall being told by the wholesaler sales rep that the advent of Canadian-brewed Foster’s Lager was calculated to make retailers very happy.

The rep outlined his case:

(a) Canada is a foreign country, too, therefore Foster’s is still “imported”

(b) Consequently the wholesale price will be less than when it was imported all the way from Australia, because trucks from Canada are cheaper than boats from Oceania

(c) Consumers will happily continue to pay the same inflated price as before so long as the package says “imported,” and so it will

(d) And Roger, my friend, you’ll want the 50-case volume discount and to floor-stack these bad boys

Grudgingly, I conceded that (a), (b) and (c) were true statements, but nonetheless, (d) didn’t happen. He wasn’t my friend (shed a tear), and strangely, the very idea of Canadian-brewed Foster’s Lager compelled cynicism to come bubbling up from deep inside my tortured conscience.

It’s tough being a purist in any human epoch, but neoliberalism just brings a guy all the way down.

—

Fast-forward a couple of decades (and only Jeeebus knows how many multinational brewing conglomerate acquisitions) and we find Foster’s no longer being brewed in Canada, but deep in the heart of Texas, specifically in Ft. Worth, at one of several MolsonCoors breweries, or maybe now it’s Asahi (Japanese for “buy up all the breweries”), and at this juncture in the Year of Our Elon 2024, it becomes clear that the precise locale where Foster’s Lager is being brewed does not matter in the least.

(I’d suggest that neoliberalism has a knack for erasing all notions of substance, which should be obvious, and yet some of you with bulging portfolios might become testy with me, so never mind.)

Verily, there was a time when Foster’s Lager was a beer that meant something, until it didn’t, and instead Foster’s became a mutable, hollow shell into which any number of sights, sounds and images could be grafted so as to achieve the highest aim of modern multinational breweries: higher value for shareholders.

The liquid in the can? It tastes no different than Pabst — and this is hardly a compliment.

Maintaining these random visions of “Australia-ness” among consumers who don’t know any better, won’t learn, and probably couldn’t locate the seventh continent on a globe, makes as much sense as other strategy amid a marketplace crowded with nonentities.

But at this point Foster’s phrase might as well be “Mongolian or Nigerian or Basque for Australian for beer,” or some other marketing campaign predicated on utter recurring nonsense.

Granted, Foster’s Lager might still pertain to localism coherently assuming one has the time and money to leave America on a jet plane, arriving at a coordinate somewhere around the corner from an Australian koala encampment — except with the brand having fallen well south of the “most popular Australian beers” list in its original home country, there’s no guarantee you’d find it even then.

And yet here’s the rub, massively strange but true: Whether Foster’s Lager is brewed in Australia, Canada, the United States or Bolivia, its aura of a requisite Australian pedigree lingers, as accrued by decades of deceptive marketing.

Beer drinkers still associate Foster’s with Australia, in spite of all evidence to the contrary.

Consider the concurrent image of an otherwise watery and insipid American legacy beer like Coors Banquet, now back in vogue because of enduringly clever product placement within modern-day boob-tube Westerns like Yellowstone. Coors as an indistinct product owned by a multinational corporation conjures the Rocky Mountain subsection of The Great American Outdoors, which is not to be confused with The Outback, Australia’s vast, mostly arid inland expanse.

Accordingly, maybe Coors should be the house beer for the Twin Peaks bar and restaurant chain.

—

I’m examining all these zombie Foster’s Lager factoids for an unexpectedly prosaic reason.

My daily posts at this portal concerning food and drink in Louisville require a featured photo, which then appears as enticement on F & D’s linked social media feeds. If we don’t have an image in the archive, or I haven’t been provided with one, I generally try to pull a usable photo from the establishment’s web site or social media pages.

Facing just such a contingency, my recent post announcing the imminent closure of Harvey’s (2011 Frankfort Ave.) — cheese shop by day and a unique Sydney, Australia-themed café by evening (the final business day will be July 20, 2024) — needed a featured photo, and I found a great one: gorgeously slathered burger, bottles of Lindemans wine from New South Wales (the winery was founded in 1843), and, incongruously, a stubby little Coors Banquet beer.

I scratched my head. Surely there must be some sort of Australian beer coming to America these days that would make a more suitable conceptual pairing, maybe a craft beer brewed with characteristic hops from Down Under.

Even the aforementioned, orphaned Foster’s Lager would conjure sufficient imagery. After all, right in the middle of my Australian ruminations, the fellow behind me in line at Kroger placed a six-pack of Foster’s on the checkout conveyor belt, a phenomenon I haven’t witnessed in New Albany since the Nineties. I couldn’t resist asking him about it, and his answer: “We went to Australia a while back and this beer reminds me of the trip.”

Fair enough.

Then I read the post by Harvey’s more closely and came to the belated understanding that management was promoting a special weekly burger with a glass of wine or beer for under $20.00, which is a laudable pursuit and explains the photogenic presence of Coors Banquet owing to its favorable non-union wholesale price point (while Foster’s from Texas is an import and presumably priced accordingly — although I suppose Asahi might be non-union, too?)

The gist of it is that not much Australian beer (implying beer brewed in Australia, not Ciudad Juarez or the South Pole) comes to the United States. The bigger, older and better-names of Australian beer are vended only at home, or they’re components of multinational corporations and can be contract-brewed elsewhere, while smaller craft-oriented breweries are faced with the same costly “distance to ship” economy of scale as sent multinational Foster’s fleeing to the habitat of the late, lamented J.R. Ewing.

—

Embittered and angry old beer business hands like me readily will recall that once upon a time, when practitioners of beer enthusiasm sought wisdom, as opposed to worshipping cleverly photographed images of AB InBev-produced Goose Island Bourbon County Stout (Cheesecake Factory Barrel Aged) bottles, there was in fact a unique style of beer indigenous to Australia.

It was called Sparking Ale, and it exists even today, The Beer Judge Certification Program even describes it.

A well-balanced, pale, highly-carbonated, and refreshing ale suitable for drinking in a hot climate. Fairly bitter, with a moderate herbal-spicy hop and pome fruit ester profile. Smooth, neutral malt flavors with a fuller body but a crisp, highly-attenuated finish.

During the 1980s Coopers Sparkling Ale, widely acknowledged as the best example of the style, occasionally made its way into Indiana, where I stocked six-packs at Scoreboard Liquors.

Happily, in 2024 the founding family of Coopers remains in control of the brewery, and it is the largest in the country owned by Australians (not Brazilians or Russian oligarchs). 35 years ago the twist was that Coopers Sparkling Ale came to us bottle-conditioned, and nowadays the same is true of the brewery’s cans. Roll them before opening to stir the yeast.

Happily, in 2024 the founding family of Coopers remains in control of the brewery, and it is the largest in the country owned by Australians (not Brazilians or Russian oligarchs). 35 years ago the twist was that Coopers Sparkling Ale came to us bottle-conditioned, and nowadays the same is true of the brewery’s cans. Roll them before opening to stir the yeast.

I always wondered if this natural method of carbonation helped withstand the lengthy trip from Adelaide to New Albany.

In America, Coopers Sparkling Ale is imported via Total Beverage Solutions of South Carolina, and consequently might be available hereabouts; kindly let me know if you spot it, because this article was formulated on the fly, and I’ve run out of time to go foraging.

(Update: according to the product finder at Total Beverage Solutions, the closest Cooper Sparking Ale stock is at Jungle Jim’s near Cincy.)

Last year at Good Beer Hunting, Rob Horner wrote about Coopers and Sparkling Ale through the ages.

Australia’s Only Native Beer — How Coopers Helped Sparkling Ale Survive into the Present Day

Over the last few decades, many steps have been taken to modernize the operation, including stylistic experimentation, a highly successful venture into the homebrew market, and most recently leaning heavily into a shift from the historic brown bottle to modern cans. But it is the unbroken thread of traditional Ale production that keeps Coopers fans coming back.

Has a Louisville-area brewer ever made an Australian-style Sparkling Ale? It seems likely, although I can’t recall. I’m wondering because I find myself contemplating creative local partnerships.

For instance, there’s another vaguely-themed Australian establishment in town, the recently opened Moonsong Bar and Café (sorry, I can’t bring myself to perpetuate the use of the + sign as a conjunction; I dislike the practice almost as much as Coors Banquet itself).

Moonsong, located at 710 E. Jefferson St. (in the Tempo by Hilton Louisville Downtown NuLu) might choose to decline both Coors and Foster’s by commissioning a house Australian Sparkling Ale from a local brewery with excess capacity (translation: just about all of them). Kentucky has small brewery self-distribution, making the process even handier.

Just think: a unique locally-brewed ale (whether it’s bottle-, can- or keg-conditioned isn’t important), available only at the contracting establishment and its contract brewer’s taproom, and one that is not the usual mass-market American carbonated dishwater, but also not an import that has been stripped of its geographical essence.

Rather, it would be an homage to a genuine Australian beer style, served at an establishment seeking Australian shading, and symbolic of a bar or restaurant taking its beer selection as seriously as its other offerings.

Oops … am I guilty of pie in the sky — again?

Admittedly, this notion of an Australian Sparkling Ale revival is unlikely here in River City, but at least it reflects a semblance of purposeful, cooperative design, which is utterly lacking whenever bars and restaurants allow their on-premises beer selection to become an ad hoc, last-minute, sloppy-seconds collection of disparate brands that adds up to nothing sensible, even as they’re perfectly capable of thoughtful wine, bourbon and cocktail lists.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m studying the parameters of British Best Bitter, and other low-gravity session ales that pair well with food. There might be a project in the offing, and I’ll keep you posted when it comes to fruition.

Previously at “Hip Hops”:

Hip Hops: 20 years on, and maybe at long last we’ve reached post-postcraftbeerism

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with