Compo Simmonite: “I could murder some fish and chips.”

Foggy Dewhurst: “You usually do.”

Norman Clegg: “If ever there’s been a neglected subject in poetry, it’s vinegar.”

Last week’s market pub contemplation prompted further thoughts on a theme of the leisurely consumption of real ale, a reverie that led me to the venerable British television series, Last of the Summer Wine.

It’s hard to imagine a more unfashionable concept in the milieu of the smart phone, driverless car and sour pickle beer.

Perhaps that’s why I’m so attracted to the show.

For the uninitiated, Last of the Summer Wine ran from 1973 through 2010, an astonishing 37 years, with almost 300 episodes aired. Virtually all of them emphasize a timeless sense of place, with much location filming amid the workmanlike stone buildings and rustic, gorgeous rolling hills of Holmfirth, Yorkshire.

It’s “a whimsical comedy with a penchant for light philosophy and full-on slapstick (following) the misadventures of three elderly friends tramping around the Yorkshire countryside,” a basic narrative premise remaining unchanged throughout the program’s lengthy run.

Reruns of Last of the Summer Wine have been showing on KET (public television) for as long as I can remember, and while the electronic media of today’s world might enable one the selective luxury of binge viewing on-line, the series itself decidedly isn’t about today’s world.

As such, I prefer the old-fashioned manner of viewing: Pouring an adult libation (British heritage beers like Old Speckled Hen work particularly well) and sitting motionless in front of the television at 6:00 p.m. on Sunday with the missus, who after all is a citizen of the United Kingdom.

On those occasions when life gets in the way, there remain hundreds more episodes to watch, then watch again.

Last of the Summer Wine’s pilot episode was filmed in 1972 and aired in 1973. Astoundingly, plot elements subsequently enjoying a shelf life of decades are found to be largely intact from the very start, although I’d argue that the word “elderly” isn’t really a valid descriptor of the primary male characters, at least in the beginning.

In fact, while the first trio (Cyril, Clegg and Compo) might accurately be described as redundant, pensioned or retired, the actors portraying them, as well as their fictional characters, were in their early- to mid-50s when the series debuted in 1973. Along with various successors, they certainly became certifiably elderly, but what are the odds of a television series lasting almost four decades, anyway?

Last of the Summer Wine kept going and going, and along the way, there were minor changes, tweaks and periodic major cast turnovers. The character of Cyril was replaced by Foggy Dewhurst, and then Seymour Utterthwaite; Foggy later returned, and was replaced a second time by Frank Thornton’s Herbert Truelove. Actor Bill Owen (Compo) died in 2000 – and so did his character. Peter Sallis’s Clegg aged the most; he appeared in all 295 episodes and died at 96 in 2017.

In the very beginning—insert a shocked “gasp” here—these three pensioners were younger (their mid-50s) than I am now. This, dear readers, boggles my mind, and it speaks to the endlessly convoluted mind games of time and history.

As an example, consider Foggy, who constantly exaggerates his experiences in the Asian Theater during the Second World War. When Foggy came to town in 1976, it had been only three full decades since the end of the war, which as we know initiated a post-war baby boom … which in England produced the earliest fans of a group like the Rolling Stones … who in 2023 will celebrate its 61st birthday.

I remember an episode from 1991, in which Foggy encountered a man on the street in Holmfirth using an ATM. By contrast, the 1973 pilot episode might as well have been filmed in the 1920s. Modernity in Holmfirth was purely relative. One detects an absence of overall hurry, and few items appear to be made of plastic. Anglicanism isn’t dead, and there are more bicycles, buses and tractors on the street than automobiles.

Into this throwback tableau stepped Clegg, Compo and Cyril. Apart from wartime service, these former schoolmates never left their nowhere town. Once retired, with nothing to do, they wandered about hill, dale and high street, reminiscing and philosophizing, and indulging in harmless antics inspired by boredom, far more in keeping with children’s play than a senior community’s social scheduling.

A worthy ideal, indeed — and at any age. Where do I sign up?

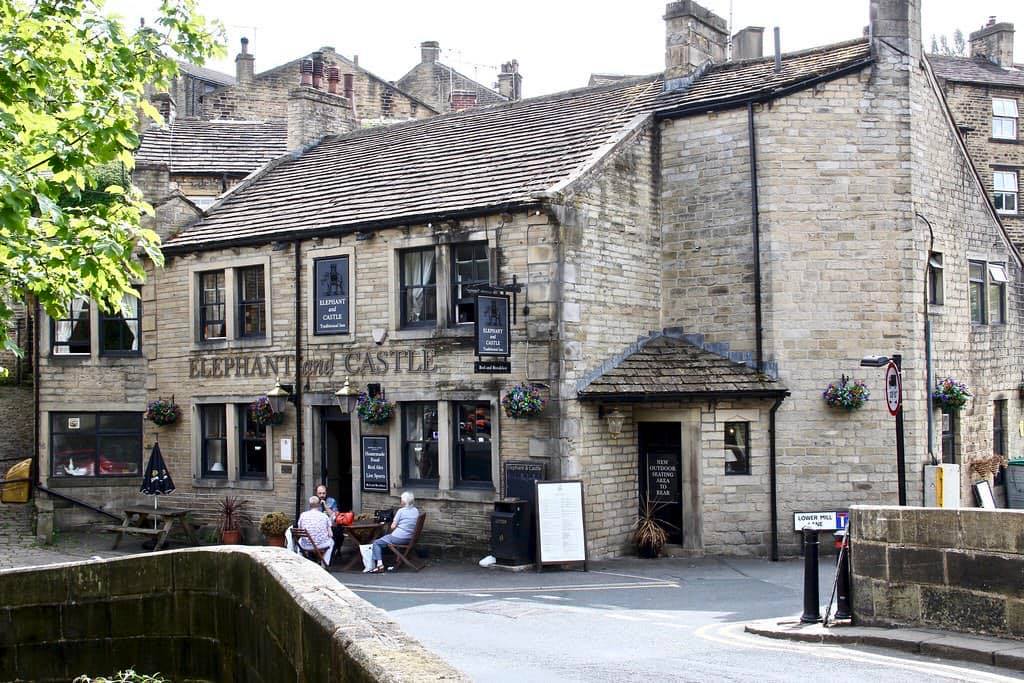

The trio’s day invariably brought them to Sid’s Café for tea and sticky buns, and often included extended sessions in various Holmfirth pubs, including the White Horse Inn, Butcher’s Arms and Elephant and Castle. In these intimate bricks and mortar monuments to Real Ale when it really was real, they enjoy leisurely pints from the hand-pull while hatching the next scheme.

Periodically there was disagreement over who was up to buy the next round, but three more pints generally materialized in front of them, to be deliciously drained.

(Was there ever an episode of Last of the Summer Wine when the drink of choice was wine?)

Know that because the title character of the original Inspector Morse series specifically addresses the virtues of traditional cask ale at regular intervals, he probably remains the foremost telly-centric exponent of traditional British ale-making virtues, albeit leaning a bit toward the geekier side of things. I adore him for it.

Last of the Summer Wine also ranks highly, if for no other reason than its depiction of the pub experience in such affectionate fashion, as a daily component of the well-rounded ne’er-do-well’s life. Of course, this is the whole point of a pub, and I thank the series for making it.

Not only that, but I salivate and become messily Pavlovian. I see the Holmfirth lads lifting their pints, and for the briefest of moments, the stress-ridden workaday routine disappears from view.

In a daydream, I join my pals Mark and Graham or Jerry, shuffling through the streets of New Albany, solving the world’s problems, and repairing to a clean, well-lighted place for liquid sustenance. We hector politicians, recall the good old daze, and toss a water balloon at a passing tractor trailer.

Alas, it can’t ever be the same, although a boy—and even an older man—can dream.

Or, conversely, he can watch Last of the Summer Wine and envision the art of the possible.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 40 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 40 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.