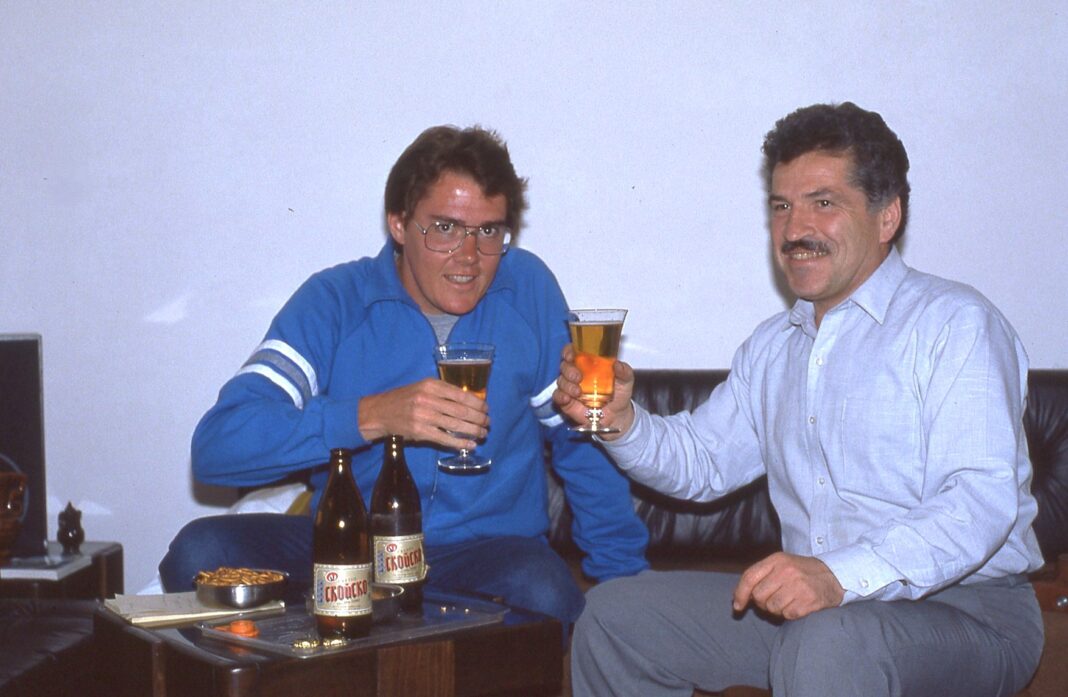

I’ll grant you that portions of this story do not pertain specifically to beer, although judicious quantities of Скопско пиво (Skopsko Pivo) were consumed in late May of 1987, when a bumbling 26-year-old hick from somewhere near French Lick (New Albany, Indiana to be precise) found himself afoot in Yugoslavia, a nation that ceased to exist amid horribly excessive violence during the 1990s.

Skopsko Pivo is still produced by a company that began brewing it in Skopje, North Macedonia in 1924 and was purchased in 1998 by Heineken along with a consortium Greek corporate investors. Back in 1987 it was a crisp, clean and competently rendered golden lager, and I’m curious to see how it tastes today.

In fact, right about now I should be finding out. In the interim, here is the tale of my previous visit to Skopje. It took place on a different planet; at least that’s the way it feels.

—

May, 1987

The journey from Dubrovnik to Skopje by bus, train and my own two feet was an inadvertent and completely ridiculous exercise — a farce, if I’m to be truthful. But I wouldn’t trade it for anything because it led to an unforgettable experience in a place I’d initially not planned on going.

Tuesday, May 26, 1987 was Day 41 of my European excursion, beginning in the seaside city of Dubrovnik (now within independent Croatia) with a bus bound for Belgrade (today’s Serbia) at 5:00 a.m. The bus route to Belgrade included a brief rest stop in the scenic mountains at the brutalist WWII Tjentište War Memorial (a spomenik) in rural Bosnia — in 2025, known as Bosnia and Herzegovina.

At roughly three in the afternoon on a pleasant springtime Tuesday, after a ten-hour bus ride from Dubrovnik, I was standing outside the combined train and bus station in Belgrade looking for the many enterprising socialistic Serbs who’d be competing, capitalist-style, to rent me a room in one of their flats.

Or so I’d been assured.

I was mindful of the Let’s Go: Europe guidebook’s accompanying warning: “The difficulty of finding adequate accommodations is probably responsible for 90% of Belgrade’s bad reputation among travelers.”

The book helpfully advised bargaining with these inevitable room hawkers outside the station — and as an even better alternative, strongly recommended visiting a generally helpful tourist information office nearby in the underpass at Terazije Square.

The problem? There were no room hawkers outside the station, not even one. I milled around for at least an hour, looking as cluelessly touristic as possible (a task that certainly wasn’t hard), and still they remained artfully hidden. I even asked a couple of cab drivers, who only shrugged indifferently.

The tourism desk in the train station was pleasant but unequipped to help travelers like me find lodgings. The only hotel I saw nearby was out of my price range and had no English speakers on duty. At this point I should have walked the scant quarter-mile to the Terazije square office mentioned in Let’s Go, and yet for some reason I refused to go there.

Why not?

An innate stubbornness probably helped me later in business, but it isn’t among my noblest of traits, and evidently I was having a bad day and feeling ripe for one of those childish temper tantrums that usually left me in far worse condition than before. Eventually I retreated to a dingy cafeteria across one of the side streets by the station for a meal of dirt-cheap leathery roasted chicken, rock-hard vegetables and wilted salad.

The beer was passable, and I may have had two. It’s conceivable that I took a couple more with me in bottles.

Back at the station, as yet bitchily refusing to abandon the notion that someone should materialize to offer me an inexpensive bed, those beers compelled me to use the WC. It was found quite readily by following my nose, as one of the toilets therein had disintegrated, and a rancid mixture of water and sewage cascaded as if from a fire hose from the vicinity of the stalls, flowing out the door and across the floor, into the common area and onto the train tracks.

Needless to say Belgrade wasn’t impressing me very much, so it was time for an escape plan, as revealed by studying the rail schedule. A brzi (“fast” — just a sad euphemism) overnight train to Skopje was listed for departure at 11:45 p.m., with arrival the following morning.

Now this idea had possibilities.

I could nap in my seat, and after all I “knew” someone in Skopje: Radojko “Rady” Petkovski, an amiable seismologist who’d chatted with me on a previous train from Ljubljana (Slovenia) to Zagreb (Croatia). Surely I could find him, get some local advice on cheap rooms, and hang out for a few days in Skopje.

The decision was made, and I bought a second-class ticket for Skopje. Several days later, returning to Belgrade by rail from Bulgaria, I made a second and more determined effort to spend the night there by actually boarding a tram and locating the Yugoslav capital city’s sole accredited youth hostel, only to find it in the final stages of complete stacked-rubble demolition, with a replacement structure vowed to be built and ready for occupancy by the time of my next visit in 1989 — or a follow-up that still has not occurred.

In other words, welcome to Skopje, which seemed hopeful.

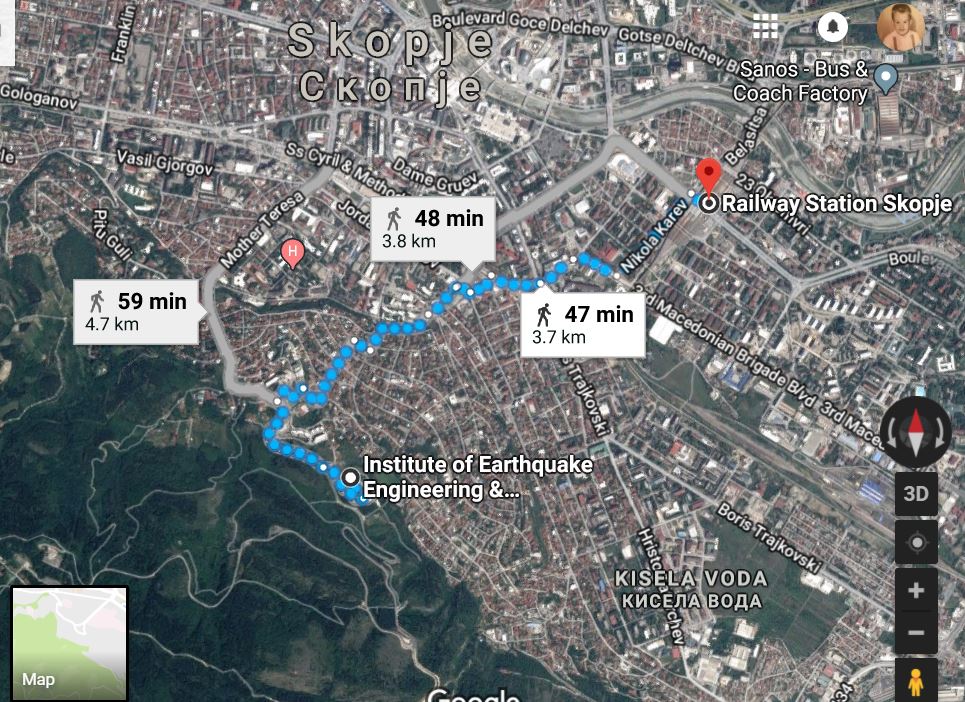

To be more detailed, upon arrival I armed myself with a city map and Rady’s business card, electing to walk to the earthquake institute, his place of employment, which was about two miles from the train station.

I must have been getting more adept at map reading, because the institute was exactly where it was supposed to be, up there, perched on the hillside.

I presented the business card at the guard shack. The booth attendant stared, incredulous, then picked up the phone. I was motioned toward the entryway, to be met by a young English-speaking colleague of Rady’s named Alexander, who informed me that Rady was attending a meeting.

Alexander listened intently as I told him my story, then flabbergasted me by inquiring where in America I’d studied seismology. Taken aback, I replied that I’d majored in philosophy, not seismology, whereupon I learned Rady was somehow convinced that he’d met a fellow scientist on the train, not an itinerant Hoosier bartender.

Suddenly I was worried.

I’d harbored absolutely no intent to mislead Rady, and yet Alexander’s demeanor was very serious. All I could think to say in order to lighten the mood was that while I wasn’t an earthquake professional at all, my home was situated somewhat near the New Madrid fault, and things might yet get interesting.

He laughed, and finally I managed to breathe. When Rady emerged and heard the explanation, he smiled, too. Soon coffee was being made and selection of delicious sweets appeared; guests in the Balkans invariably are pampered with caffeine and sugar, and I’d had nothing to eat since the rubber chicken in Belgrade.

I agreed to meet Rady later in the afternoon at the station, where I’d left my backpack at the luggage storage room. He pulled up in a late 1970s model Zastava (known as “Yugo” for export only), often derided in America as among the worst cars ever built. My new friend was a highly skilled urban driver, deftly manipulating a balky manual transmission.

This Google street view from 2014 may or may not show the building (on the left) where Rady lived at the time, but if not it’s very reminiscent of the neighborhood. These were desired places of residence close to the city center, with amenities in the vicinity and public transit connections.

And so it transpired that Rady dismissed any conceivable usefulness of a hostel or hotel and opened his apartment in Skopje for five nights to a complete stranger from America, awarding me his couch for sleeping, quickly exhausting his limited English, showcasing the local sights during the scant free time he had, putting me on a round-trip bus to Lake Ohrid for a day trip, and finally driving me back to the bus depot stupidly early in the morning when it came time for my getaway to Bulgaria.

I happily purchased the beer. Most importantly at the time, I was able to bathe and wash my clothes. It had been 48 hours since my last shower, and I felt like a complete greaseball.

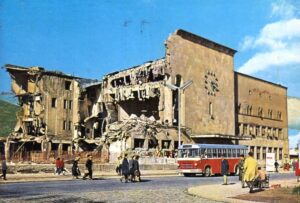

Skopje’s dwellers are very interested in earthquakes because earthquakes have a thing about Skopje. The most recent major earthquake struck the city in 1963, killing over 1,000 residents, injuring almost 4,000 others, and leaving more than 200,000 people homeless. About 80 percent of Skopje was flattened, and among the architectural casualties was the railway station, built in 1938.

The station ruins were left standing to serve as a monument to the devastation of the earthquake and the lives it claimed, although it has since been partially rebuilt to function as a museum. The exterior clock is stopped at the moment of the earthquake’s impact.

On Friday, May 29 I traveled to Lake Ohrid and back. The town of Ohrid was a three-hour long trip each way by bus, but Rady had scheduled a long day at work, the ride was cheap, and I had ample time on my hands. One memory that stands out was a woman on the bus listening to a transistor radio, and the song “Papa Don’t Preach” by Madonna playing hourly. It seems pop radio saturation worked the same in socialist Yugoslavia as in the capitalist USA.

Ohrid’s adjacent lake is one of Europe’s deepest and oldest. Lake Ohrid’s ecosystem is unique and much studied, and I’ve always been glad I endured the six-hour roundtrip commute with Madonna. Speaking of which, the Church of St. John the Theologian might be the most photographed man-made object in Ohrid.

Hermetic Albania was completely inaccessible in 1987, even if visible on the other side of the lake. It was the second time I could see Albania, but not touch it (spoiler alert: the time finally came in 1994).

If memory serves, Rady was divorced or separated and had a son, Milan, who lived with his mother. If I saw Milan at all during my visit, it was for a very brief time; he’d have been only a boy. There was time during the weekend to experience a bit more of Skopje, and once familiar with the location of the old bazaar area, I returned several times to eat grilled ćevap, a type of fragrant homemade sausage.

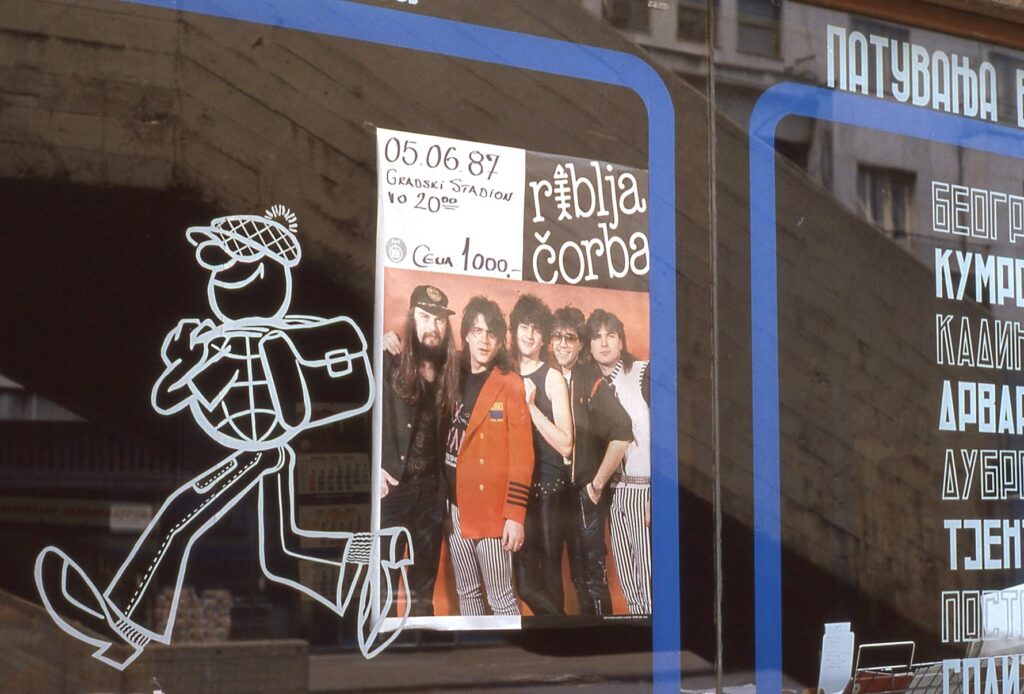

There was fish stew, too, although not the edible kind.

Riblja Čorba (Serbian Cyrillic: Рибља Чорба, pronounced [rîbʎaː t͡ʃɔ̌ːrba]; translation: Fish Stew) is a Serbian and Yugoslav rock band from Belgrade. The band was one of the most popular and most influential acts of the Yugoslav rock scene.

The poster reads 5 June 1987, which means I missed one of the region’s biggest names by less than a week.

A walk along the Vardar River provided this view of the Stone Bridge, completed by the Ottomans in 1469, and a symbol of Skopje ever since.

In the wake of the earthquake’s devastation, the Yugoslav central government vowed to rebuild the city in modernist fashion, and uncommonly among socialist nations, campaigned openly for international assistance in commencing a recovery plan. This fascinating story is told here: Skopje’s 1963 Quake: From Ruins to Modernist Resurrection, by Donald Niebyl at his Spomenik Database.

They decided that a special group should be brought in to develop a special City Center Plan that would formulate a showpiece and modern world-class downtown district for the city. Thus, in December of 1964, eight architect teams (4 Yugoslav & 4 international) were invited to participate in a competition for formulating this new plan.

The plan was only partially realized, and since North Macedonia’s independence, Skopje has endeavored mightily to reverse the footprint of the brutalist architecture that came about as a result. A prominent example in 1987 was the post office complex. Subsequently it was neglected and then damaged by fire, but rehabilitation efforts might be under way as of 2023.

The statue is a monument to the liberation of Skopje during World War II, and behind it can be seen the rebuilt walls and towers of the fortress, which in turn lies near the historic bazaar.

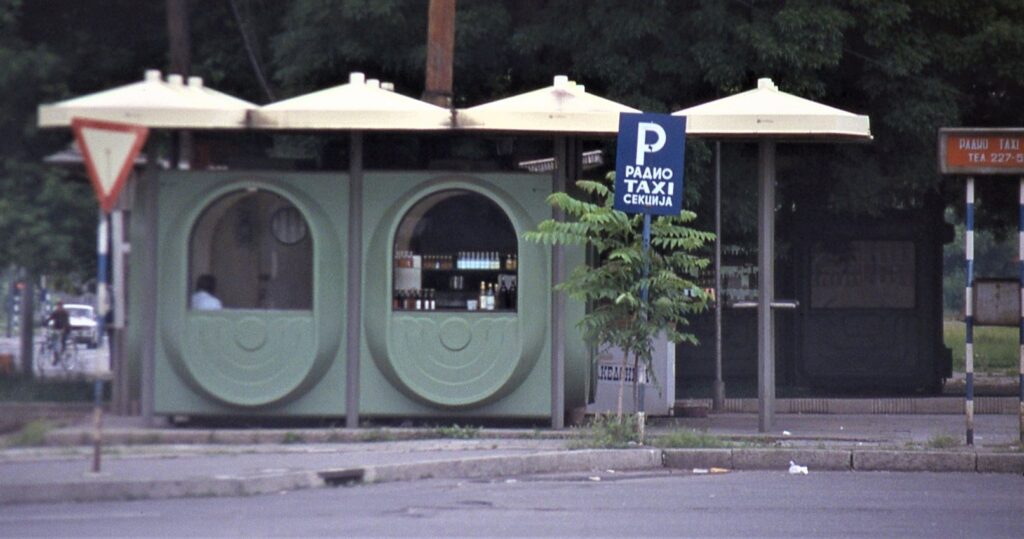

Finally, one of the ubiquitous kiosks, this one located by a taxi rank. Most were clustered around transit points, and I loved them. While there might be seating space inside, most customers grabbed a beer and a sausage while standing outside. There were several standardized designs of such kiosks in Yugoslavia, the most enduring of which was the K67.

I was in Skopje long enough for several interesting side conversations to develop with Rady. One of these was the prospect of exporting Skopsko Pivo to America. Neither my knowledge nor resources was sufficient to achieve this, but I promised to make contacts once having returned home.

Of course nothing came of it, as was the case with a friend of Alexander’s named Pero, who was eager to emigrate to the United States. Well into 1988, I kept a tenuous correspondence alive toward this end, although the truth was that as with the beer importing idea, I simply didn’t have the wherewithal (cash, clout, connections) to be of help.

On Monday morning, June 1, Rady dropped me off at the bus station and I took my place as one of seven passengers to Sofia, Bulgaria, and the only American aboard. The Bulgarian border guard made theatrical gestures as if to confiscate the subversive literature in my pack (the aforementioned Let’s Go: Europe) but the maintenance of a bureaucratic pique proved too exhausting for his pay grade, and he let it ride.

Time passed; life went on. Correspondence went cold. Five years after my visit, Yugoslavia was in the process of consuming itself; thankfully Macedonia did not feature in the worst of the conflict, and I always trusted that everyone I met was safe. The closest I’ve come to Skopje since 1987 was Albania in 1994; that is, until 2025.

Odd, the turnabout.

In 2008, it occurred to me to write about the Yugoslav segment of the 1987 trip, which was published at my blog. The story of making the acquaintance of Radojko “Rady” Petkovski was told, wherein I mentioned searching his name on the internet and seeing a few highlights of the seismologist’s career in the form of his published research papers.

Shortly after the piece was published, a comment appeared.

I googled the internet for the same reason as you did, and I found your text. My father was Radojko Petkovski, Prof D-r. seismologist, who maybe you met in the train, probably returning from his visit to his brothers in Slovenia. It gives me a smile to see that he made an impression on you during your short time together. Sadly, he passed away on 1st of June 2007.

Best regards, his son, Milan

P.S. I can write you what happened after, since most of my youth has gone through that bloody period, but it will just ruin my smile.

It’s always good to know, although knowing also can be sad. In the larger scheme of things, I’ve no idea how “good” of a man” Rady was in the glib sense of things, or whether I am, either. Approaching 65, I can no longer be certain how we calculate these matters, or even whether it is possible to do so.

However, during those springtime days in Skopje in a far-off, lost era over bottles of cool Skopsko Pivo, I thoroughly enjoyed Rady’s company. He was extremely gracious and helpful to this scattershot budget traveler, and his hospitality will never be forgotten.

Thanks again Rady, and may you rest in peace; best wishes to Milan, wherever you are.

Previously at “Hip Hops”:

Hip Hops: Why I’m pumped about Monnik’s new Rose Hill Lager Haus

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with