Nothing could be more common than the salt and pepper on our tables. In our cuisine these two seasonings are always paired. Their containers are as alike as two eggs, indistinguishable except for the inscription on each. Yet in coupling them this way, two distinct epochs of world history are being conjoined. Salt and pepper represent two fundamentally different phases of human civilization.

Welcome to the Edibles & Potables sector at Food & Dining Magazine. It’s a place for rambling far and wide on Sunday mornings, and considering topics outside our customary coverage area.

Today it’s a good book, beginning with a confession: I’m not in the habit of compulsively re-reading books, even those that prove to be influential in my life. Of course, there are exceptions:

- The early beer writings of Michael Jackson, as in The World Guide to Beer

- The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, a sobering tome by John Barry

- Jim Bouton’s ribald baseball tell-all Ball Four

- A Confederacy of Dunces, the classic New Orleans comic novel from John Kennedy Toole

- A Distant Mirror, medieval history by Barbara Tuchman

Another personal favorite is Tastes of Paradise: A Social History of Spices, Stimulants and Intoxicants by the wonderfully named Wolfgang Schivelbusch.

Another personal favorite is Tastes of Paradise: A Social History of Spices, Stimulants and Intoxicants by the wonderfully named Wolfgang Schivelbusch.

He is not a Groucho Marx character from Duck Soup, but a very real German-born (1941) cultural historian operating from “the perch of an adroit and amiable Marxist sociology,” as Publishers Weekly once put it.

27 years after Schivelbusch’s Tastes of Paradise book was first published in English (it dates to 1980), I still consult it with frequency. It’s neither long nor “heavy,” and boasts thoughtful essays on coffee, chocolate, tea, tobacco, hashish, opium and alcoholic beverages. Taken together, these have the effect of guiding readers from the Middle Ages through modern times, with the focal point being not pharmacology, but sociology.

For instance, there is coffee.

“The logic of coffee drinking for Arabic-Islamic civilization is incontestable,” Schivelbusch writes. “As a nonalcoholic, non-intoxicating, indeed even sobering and mentally stimulating drink, it seemed to be tailor-made for a culture that forbade alcohol consumption and gave birth to modern mathematics. Arabic culture is dominated by abstraction more than any other culture in human history. Coffee has rightly been called the wine of Islam.”

When the Muslim world introduced Europe to coffee, the beverage’s “dry” and sobering qualities were aligned perfectly with developing notions of a work ethic in the context of expanding capitalism – or, the junction where Calvinism meets the Industrial Revolution. Coffee made workers more efficient, while alcoholic beverages rendered them less productive.

Even today, while at work, you’re generally free to consume as much coffee as you please, although not ale or lager … and that’s a shame.

The 17th-century coffeehouse in Europe’s evolving commercial hubs was the milieu of a new breed of bourgeois technocrat. When coffee migrated to people’s homes during the following century, a private sense of bourgeois consciousness came along with it.

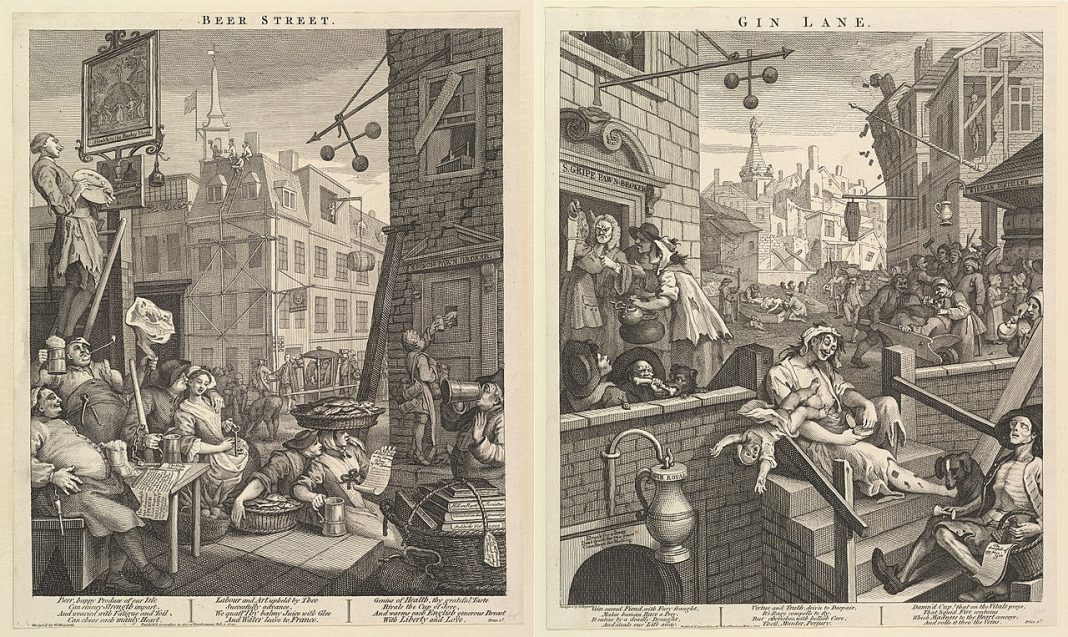

Schivelbusch depicts beer as a pre-industrial, communal and organic beverage, reflecting the pastoral ethos of the countryside, and inexorably grounded by nature’s limitations on the maximum alcoholic strength likely to be attained through simple, traditional techniques of fermentation.

Distillation – again, a concept brought to Europe by the learned Arabs, who used the process in chemical experiments – provided the means to concentrate the strength of alcohol as a beverage, subsequently wreaking havoc on human beings unaccustomed to the potency of distilled spirits, or to living conditions in their new, oppressively squalid urban industrial slums.

Consequently cheap gin was the crack cocaine, meth and opioid of its day, offering pain relief and escape during the scarce hours between ceaseless shifts at the factory, which in turn yielded just enough cash (or credit at the company store) to begin the cycle anew.

You see, it really does matter where your trendy sneakers are fabricated.

Schivelbusch makes it clear that while alcohol has been subject to abuse since the beginning of time, temperance movements as we know them today came into being only when liquor became inexpensive, common and widely ingested.

In the end, liquor’s debilitating tendencies became too much even for the exploitative robber barons, who formerly had deployed the liquid as pacifier. Reversing course, the accumulators of capital abruptly forged an unholy alliance with religious fundamentalism.

As a local example, by the late 1800s the Indiana city of New Albany’s much-lionized plate glass magnate, Washington C. DePauw, was providing financial support for the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) – the latter agitating for the complete prohibition of alcoholic beverages, either when on the clock or off it.

New Albany’s branch of the WCTU operated from the cozy confines of its downtown reading room, located in a long-demolished house that occupied the space where NABC’s Bank Street Brewhouse once operated, and Monnik Beer Co. soon will.

I like to think that in this way, adaptive reuse assists in helping to pay back the WCTU with each pint of locally brewed goodness that we enjoy.

—

This brings me to one of the most fascinating aspects of American “craft” beer’s ascent in the first decade of the 21st century, this being the rise of a strange reverse snobbishness on the part of “craft” beer drinkers, which I’m happy to say has receded somewhat in more recent times.

As small scale local brewing returned to cities like ours, many beer drinkers of a new generation announced their refusal to drink these new local beers; rather, they breathlessly awaited the arrival of the newest, trendiest, greatest beer product lines from breweries somewhere else – east coast, west coast, or anywhere else, just so long as it wasn’t down the street.

You’re to be spared a digression into “solipsistic beer narcissism,” as I termed it then. The point is that these behavior patterns reminded me of Schivelbusch’s fascinating explanation of the medieval spice trade’s true meaning.

It turns out that fascination with the exotic and far-off is as old as humanity. When the spice trade commenced in Europe several hundred years ago, the newly posited “need” to obtain previously unknown Oriental spices was much less about their supposed usefulness in masking otherwise rancid food, as is often erroneously imagined today (medieval cooks knew perfectly well how to smoke and pickle), but because the spices themselves were quantifiable, visible measures of social status according to prevailing subjective value systems.

In essence, back then, anyone who was anyone just had to have these spices – or, risk not being anyone, any longer. Possession of Oriental spices was a palpable, tangible symbol of social status, and the key to their value was a base reality: These spices were from somewhere else – mysterious, expensive and hard to obtain, and therefore infinitely sexier than piddling local norms.

But it went even further, into the realm of sheer mysticism.

In the beginning, spices symbolized the superiority of the far-off lands from whence they so rarely came to rest atop one’s table. If the spices themselves were imbued with magical and totemic properties, then surely it proved conclusively that the other side of the planet was superior to the mud, blood, poverty and ignorance of Europe, and not unlike heaven itself.

Paradise simply had to be elsewhere, and spices provided tastes of this paradise. It was evidence of a raging subliminal inferiority complex, and comprised the most anti-local viewpoint imaginable.

Like the objectified beer porn selfie of the past 15 years, no one thought it necessary to bother with explanations as to why the bowl of Oriental spice proffered at the wedding feast mattered. It was understood with lightning speed.

Peers compared the quantity of their spice stashes to establish social pecking orders, and any stray servant or cowed peasant in proximity of the scene knew immediately that strength and power were conferred on those who possessed the requisite spicy symbolism … while he or she remained a degraded underling.

It’s that Billie Holiday song, all over again, like a mantra for our current pandemic year: “Them that’s got shall have, them that’s not shall lose.”

It should be obvious that I highly recommend Tastes of Paradise; paperback copies are widely available, but you might begin by inquiring at Carmichael’s or your local bookseller.

The opening quote is from Schivelbusch, and the cover photo credit is Wikipedia’s: “Beer Street and Gin Lane are two prints issued in 1751 by English artist William Hogarth in support of what would become the Gin Act. Designed to be viewed alongside each other, they depict the evils of the consumption of gin as a contrast to the merits of drinking beer.”