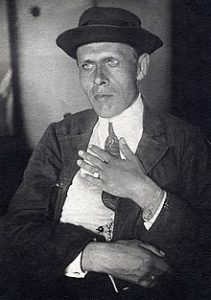

Daniil Kharms (1905-1942) was a Russian writer during Soviet times, and to our eyes the very personification of obscurity. He lived and died in an era so very far away from ours that it might as well have been a different galaxy.

Kharms eventually became somewhat known for authoring children’s books, although he was said to have disliked kids. However, any income stream in a storm; Kharms’ milieu was tumultuous, and he could never be sure of a paycheck after Joe Stalin took the reins.

It is often forgotten that during the very first post-civil-war years of Soviet rule in the 1920s there was a flowering of the progressive and avant-garde in literature, art, music, even architecture. After all, Russian society had been liberated from Tsarist and capitalist repression. Freedom had arrived.

Artistic expression wasn’t necessarily counter to Marxism, was it?

As time passed and the screws of Communist Party control inexorably tightened, the answer to this question changed radically, from “of course not,” then “not necessarily,” and finally to “yes, in fact it is — always.”

The gray areas yielded to black and white, and if artistic expression was not precisely suiting the party’s present needs, then by definition it was hurting them. Middle grounds didn’t exist, and painting the corners was viewed as outright sabotage.

Unfortunately Kharms chose the role of the eccentric, roaming the streets in a sort of Sherlock Holmes outfit, staging counter-cultural events, poetry readings and various other stunts. The authorities were not amused, but for a while Kharms managed to stay upright on ever thinner ice, until 1931 when he was sent to prison.

Surviving the sentence, Kharms returned home to start over again, whereupon he ran headlong into one of the perverse ironies of the Soviet system. Marxist-Leninist ideology decreed universal employment to be inescapable, and it was illegal to be unemployed. All citizens were required to work, and those without jobs were parasites subject to arrest, yet the government was in effect the only employer. It decided who worked and who did not.

As such, the state owned the printing presses, newspapers and publishing houses, denying Kharms access to them. The writer was not sent to the gulag to break rocks, but isolated at home and blackballed from being published. The hoary “publish or perish” dictum became literally true, and the ensuing impoverishment grew increasingly desperate during the 1930s. Hunger was a constant specter for Kharms.

We all understand that chronic malnutrition is a ticking time bomb, affecting mental health as well as physical well being. Consequently Kharms’ output was erratic. His exhibitionist behavior always had been calculated. Now it wasn’t as clear that he had complete control over it.

When Nazi Germany invaded the USSR in 1941, Comrade Stalin took the opportunity to round up presumed traitorous malcontents, among them Kharms, who was deposited in a Leningrad asylum for the insane. He died of starvation as the siege of Leningrad commenced, although in fact by this point there wasn’t much left of him, anyway.

Here’s a passage about eating and drinking from one of Kharms’ most conventional stories, “The Old Woman” (note that a saveloy is a spicy, red-colored sausage).

I opened the bottle of vodka and Sakerdon Mikhailovich put two glasses and a plate of boiled meat on the table.

— I’ve got some saveloys here — I said. — So, how shall we eat them: raw, or shall we boil them?

— We’ll put them on to boil — said Sakerdon Mikhailovich and while they’re cooking we’ll drink vodka with the boiled meat. It’s from a stew, it’s first-class boiled meat!

Sakerdon Mikhailovich put a saucepan on to heat, on his kerosene stove, and we sat down to the vodka.

— Drinking vodka’s good for you — said Sakerdon Mikhailovich, filling the glasses. — Mechnikov wrote that vodka’s better than bread, and bread is only straw which rots in our bellies.

— Your health! — said I, clinking glasses with Sakerdon Mikhailovich. We drank, taking the cold meat as a snack.

— It’s good — said Sakerdon Mikhailovich.

But at that moment something in the room gave out a sharp crack.

— What’s that? — I asked.

We sat in silence and listened. Suddenly there was another crack.

Sakerdon Mikhailovich jumped up from his chair and, running up to the window, tore down the curtain.

— What are you doing? — I exclaimed.

But Sakerdon Mikhailovich didn’t answer me; he rushed over to the kerosene stove, grabbed hold or the saucepan with the curtain and placed it on the floor.

— Devil take it! — said Sakerdon Mikhailovich. — I forgot to put water in the saucepan and the saucepan’s an enamel one, and now the enamel’s come off.

— Oh, I see — I said, nodding.

We sat down again at the table.

— Oh, to the devil with it — said Sakerdon Mikhailovich — we’ll eat the saveloys raw.

— I’m starving — I said.

— Help yourself — said Sakerdon Mikhailovich, pushing the saveloys over to me.

— The last time I ate was yesterday, in the cellar bar with you, and since then I haven’t eaten a thing — I said.

— Yeh, yeh — said Sakerdon Mikhailovich.

— I was writing all the time — said I.

— Bloody hell! — exclaimed Sakerdon Mikhailovich in an exaggerated tone. — It’s a great thing to see a genius before one.

— I should think so! — said I.

— Did you get much done? — asked Sakerdon Mikhailovich.

— Yes — said I. — I got through a mass of paper.

— To the genius of our day — said Sakerdon Mikhailovich, lifting his glass.

We drank. Sakerdon Mikhailovich ate boiled meat and I . . . the saveloys.

The passage echoes observations made by numerous writers scattered across hundreds of years of Russian literature, and will be familiar to any visitor who ever agreed to have “a drink” with a native, which is the very definition of a slippery slope.

Kharms comes to mind for this and two other reasons. Last year I read Today I Wrote Nothing: The Selected Writings of Daniil Kharms, and recently a Facebook friend posted a link to an article at Atlas Obscura: “Eat Like You’re in the USSR With ‘The Soviet Diet Cookbook.'”

THE 1939 COOKBOOK OF SOVIET cuisine, The Book About Delicious and Healthy Food, opens with a Stalinesque slogan: “Towards abundance!” Earlier that decade, famines had devastated the Soviet countryside, and the memory of food shortages was not far off. But these realities appeared nowhere in the Communist Party-issued cookbook. Instead, it served up a utopian future.

The 1939 cookbook “was intended to both feed and propagandize,” given that the most popular guide of the period dated to ancient Tsarist times: Elena Molokhovets’ A Gift to Young Housewives (1861). The USSR collapsed in 1991, and almost thirty years later there was another development, putting The Book back into the limelight.

Nearly 80 years after The Book’s first release, millennial Muscovite Anna Kharzeeva (along with her grandmother Elena*) put The Book’s culinary vision to the test. Kharzeeva’s new cookbook, The Soviet Diet Cookbook, chronicles her skeptical but warm-hearted journey through the 400-page Socialist Realist behemoth. From 2014 to 2019, she tried 80 of its recipes, from a flurry of porridges to the pickle-brine soup solyanka.

A cynic at the Facebook thread expressed revulsion at pickle-brine soup. He doesn’t know what he’s missing.

Solyanka (also spelled soljanka) gets its name from the Russian word for salt. The soup may have originated in Ukraine in the 17th century—regardless, it became beloved by Russians. This is a hearty, thick soup with salty cured meats, sausages, olives, capers, pickles, cabbage, sometimes carrots, and dill and sour cream for garnish.

Of course I wouldn’t have led with a tale of Daniil Kharms if not aware that Communism had a way of precluding the availability of ingredients needed to make such meals. Also, it’s true that any discussion of food and dining during the early Soviet era will prompt recollections of Stalin’s purposefully created famine, as mentioned in the quoted passage. It’s necessary to be aware of these realities, no less so than the Shoah.

However it’s also clear that Soviet people ate, drank and improvised. The latter is key, as tiny garden plots permitted of collective farm families came to be responsible for 20% or more of the USSR’s total agricultural output.

Regional cuisine during Soviet times also persisted in spite of pressures to the contrary. I can still remember an amazing salad of Central Asian greens and vegetables served at an Uzbek restaurant in Leningrad in 1985, followed by grilled lamb skewers (shashlik). The vodka was solid, too.

For more information, see “A Cookbook to Rehabilitate Soviet Cuisine” at the Moscow Times, then to close today’s rumination, watch this lighthearted YouTube video from The Soviet Gourmand, who presents “Soviet ‘Cuisine’ – Europe’s strangest canned food,” ranging from “surprisingly good foods to some of the most horrific culinary aberrations you could ever encounter.”

Featured photo credit: The Spruce Eats web site. Kharms photo: Wikipedia.