We’ll be gathering around the holiday table for — wait, what was that again?

We’ll be gathering around the holiday table for — wait, what was that again?

My Christmas season in 1991 was spent in the city of Košice (KOSH-it-sə) Czechoslovakia, population circa 225,000, located near the Ukraine in what is now independent Slovakia.

I was teaching conversational English to doctors and nurses in Košice’s teaching hospital under the auspices of a post-Cold War program called Education for Democracy, and thanks to the abundant generosity of my students, several holiday visits to their homes were booked well in advance.

As you might imagine, those months living and working in a locale with history dating back to the 13th century, one that had been situated behind the ideological Iron Curtain until two years prior to my arrival, made a deep and lasting impression. It was as much of an education for me as them, and 30 years later, I think about it almost every day.

As Christmas approached in Košice, it seemed the rampant commercialism to which we’d become so accustomed in the West was almost entirely absent. Nary a yuletide decoration appeared until St. Nicholas Day (December 6), and even then the visual effect was understated and subtle. Given that economic privatization was only just beginning, and most businesses as yet remained under government control, the shops and stores did not embrace a “deck the halls” approach.

Eastern Slovakia was the focus of an industrialization push during communist times, and yet once one ventured outside the larger cities, the feeling remained overwhelming rural. Precisely because so many residents of Košice had come to the city from the countryside for work at the steel mills, and at the time of my residence were only a generation or two removed from farms and villages, Christmas itself was decidedly small-town, not urban.

Even as an inveterate Grinch, I found the scene refreshing, and wrote about it in a letter home.

But Christmas is coming, and somewhere in a valley near Kosice, in the backyard of a quaint farm, a goose is getting fat. Barrels are being inspected to gauge the progress of the cured cabbage that will form the base of the traditional holiday soup. A trip to a nearby town is being planned. There will be shopping for gifts and a visit to the fish market for carp, another holiday staple ‑‑ or perhaps the fish will be vended from oversized plastic tubs, to be weighed and wrapped right on the street.

Those big blue plastic tubs appearing so suddenly shortly before Christmas piqued my curiosity, especially when I saw fish swimming in them. My students gleefully explained: those aren’t mere fish, they’re kapr, “carp” to Americans, and they’re not just carp — they’re Christmas dinner!

Why do Central Europeans in general, and Czech and Slovaks in particular, eat carp for Christmas?

Some say the practice owes to old-fashioned rituals of Catholic fasting, while others point to the long tradition of aquaculture, or freshwater fishponds, in places like Southern Bohemia (Czech Republic). Another explanation is the lower price point of carp, compared to beef or pork. Not unexpectedly, there’s more to the story, because bottom-feeders need their baths, too.

Carp for Christmas? The odd Central European tradition explained (Kafkadesk)

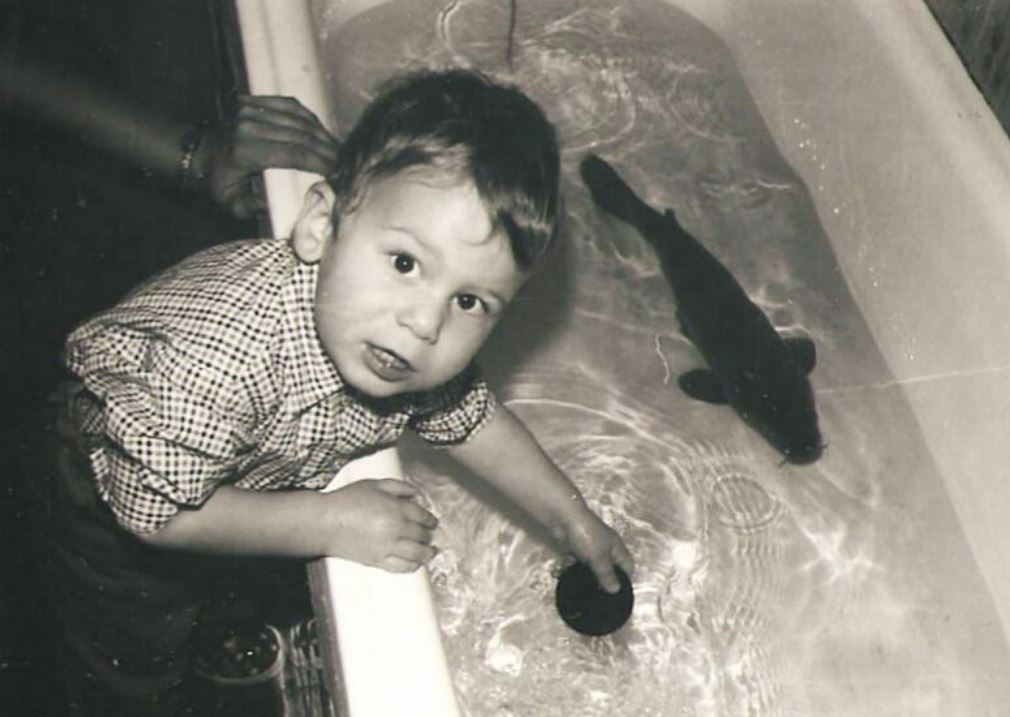

But if you thought eating carp was the strangest part of the tradition, you’re in for a surprise. What’s truly odd is what comes before: per tradition, families usually buy the carps alive a few days before Christmas in one of the many carp stalls or stands that can be found in cities throughout December… and then put the fish in their very own bathtub.

While Americans with a taste for history might be familiar with our national legacy of bathtub gin, the notion of bathtub carp is very different. Everything Czech goes into greater detail.

Czech Christmas Traditions: There’s a Carp in My Bathtub!

The carp sellers (or stalls) consist of several large vats filled with live carp in water. There is a large table where the carb is killed and prepared if you like. But to stay true to the tradition you will want to buy the carp fresh a day or so before and cook it fresh on the 24th. The folks who buy it live quickly take it home, fill up their bathtub and can you guess what happens next?

It will unofficially become the family pet for the days or hours leading up to the traditional Christmas meal.

In modern times, the carp usually is fried and accompanied by a mayonnaise-based potato salad, which was my delightful dining experience in 1991. I also was served cabbage soup, and for dessert, bobalki, or honey-sweetened balls of baked dough with poppy seeds. After three such meals on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, I’d had enough in terms of caloric intake, although by Boxing Day my students probably were happily eating peppery carp soup prepared with the remnants of the previous main course.

As with the fantastic soup from neighboring Hungary prepared with carp from Lake Balaton, slurp it carefully, because mud dwellers are quite bony.

According to numerous sources, the Christmas carp tradition in places like Slovakia and Czech Republic is waning, or at the very least evolving with the advent of frozen options. Other reasons include an overall higher standard of living, and with it a taste for Christmas turkey or red meat, as well as the main two drawbacks of bringing living fish into your home to occupy the bathtub: your children might fall in love with the carp, and if not, the ability to clean and filet it has been lost, anyway.

Speaking for myself, carp for Christmas is a meal I’d enjoy repeating. Maybe someday.

(Cover photo credit: Everything Czech)