During the years 2009 through 2016, when I was still actively engaged in brewery ownership at the New Albanian Brewing Company (NABC), I served as a director on the board of the Brewers of Indiana Guild (BIG). It truly was a wonderful experience.

Our mission at BIG was to pursue educational and promotional objectives calculated to advance the interests (and enhance the value) of small breweries doing business in the state of Indiana. The Kentucky Guild of Brewers (KGB) does exactly the same.

(It bears reminding that while the federal government has primary jurisdiction over the production of beverage alcohol, statehouses are where pesky devils reside amid their various and sundry regulatory details. Consequently, guilds of brewers like BIG and KGB naturally concern themselves with matters pertaining to their own home states.)

Now as then, BIG organizes beer fests and similar events, keeps abreast of Indiana legislative activities and Indiana Alcohol & Tobacco Commission (ATC) diktats, dispenses news and information to lawmakers, and advocates for its market segment in the wider marketplace of ideas.

For the most part, BIG discussions during my tenure were straightforward; perhaps complicated by legalese at times, but generally capable of being understood by laymen. Every now and then, we’d debate more esoteric, quasi-philosophical questions:

- What does it mean to be a brewery, as opposed to a sturgeon cannery?

- Can it be that sometimes a brewery is not a brewery?

- And, if a brewery is not a brewery, can it still be a member of the Guild?

These specific questions arose more than a decade ago when Granite City Food & Brewery of St. Cloud, Minnesota started opening satellite locations in Indiana. Came the query: Was Granite City eligible for Guild membership, and hence, able to enjoy the privileges afforded member brewing businesses?

Being headquartered out of state did not factor into it, because Granite City was by no means the first chain brewpub to expand into Indiana. At the time, both Rock Bottom Restaurant & Brewery and Ram Restaurant & Brewery were long-established presences in downtown Indianapolis (both since have closed, as has Ram’s successor, Goodwood Brewing & Spirits Indy), and there may have been others I’m missing.

Rather, the BIG board’s fundamental issue with Granite City can be summarized as Fermentus Interruptus™ (tacky, yes, but it’s a trademarked term). In short, we were compelled to ask ourselves the aforementioned questions about the nature of breweries, as opposed to tanning salons, precisely because Granite City’s model was unconventional.

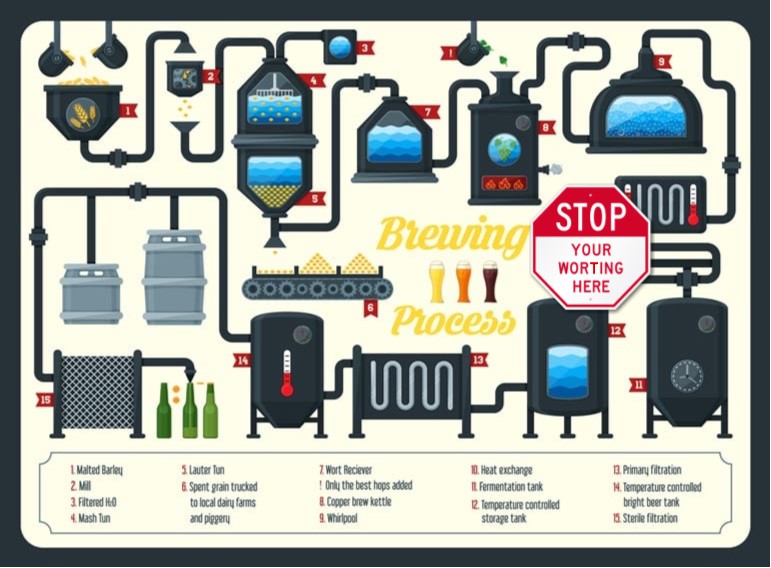

Trusting that most of my readers are familiar with the basic flow of the brewing process, here’s a helpful depiction.

I’ve inserted the stop sign to illustrate the precise point of Fermentus Interruptus™ , although strictly speaking, only the “hot side” of the brewing process (the mash and boil) is subject to suspension, given that stoppage occurs before the “cool side” (fermentation) even begins.

The phrase is cute and catchy and all. There oughta be a t-shirt. Three cheers for semantics; whatever.

Granite City’s shtick works like this: The company brews beer centrally (in Ellsworth, Iowa) but leaves the batch hanging in mid-Bock (or IPA, Hefeweizen, etc.) After the boil, the unfermented wort is cooled and transferred to refrigerated trucks, to be transported to the 16 individual Granite City outlets (down from a pre-pandemic peak of 35 or so) for pumping into their on-site fermenters. Yeast is pitched, and the beer is fermented, matured, filtered and served.

Voila! Locally brewed beer!

Maybe, maybe not. Another way to look at it is that one set of large hot side brewing system components costs far less than 35 (or even 16) of them, and requires just one trained part-time cellarman at each location, impacting payroll quite favorably compared with hiring and retaining a higher-paid brewer for each site.

To be sure, I’m making no effort to calculate the cost of refrigerated trucks, gasoline and driver pay into the equation, but I suspect Granite City has done so.

According to Granite City, Fermentus Interruptus™ is a “novel approach to maintaining proprietary beer within a multiple-site brewery/restaurant concept,” and “maximize(s) efficiency, consistency, and financial obligations.” Somewhere an MBA is billing, cooing and whispering “talk dirty to me” — all the while probably drinking hard seltzer, not beer.

Ironically (or not), I’m reminded of touring Moscow, Russia during communist times. In each urban district there were pelmeni (dumpling) dispensaries, like cafeterias, and if you happened to be loitering near one of them early in the morning, you’d see the pelmeni truck pull up to deliver enormous tubs of dumplings cooked at the central dumpling house, which staff would spill into warmers and ladle out as the patrons passed through. Now and then salt and pepper might be added.

Coincidentally, did you know that Granite City occasionally describes its own beer production facility using the words “central wort house”?

No, I won’t contest that those steps needed to finish fermenting an ale at Granite City require more skill than serving greasy dumplings to Soviet proletarians. However, it’s a difference in degree alone, because the selling point of Fermentus Interruptus™, as well as systems like it (EZ BREW springs to mind), is that in theory, the job of fermenting is so simple that your dishwasher can be trained to perform it.

So, is it still beer? Yes, it is.

Is it any good?

I tried to keep an open mind ten years ago and stopped by the Granite City location in central Indianapolis (now closed) to taste the wares. The beers were drinkable and quantifiably indicative of their style, if generic-tasting and indistinct, landing them solidly and serviceably within our great and widening “meh” middle ground in terms of craft beer character.

Obviously, Fermentus Interruptus™ is a workable way to reduce costs toward the goal of having one’s own house beer.

—

Now let’s return to the definition of “brewery,” both philosophically and in the real world. BIG’s legal counsel reminded members of the board that we could not exclude Granite City from the guild by reason of it being out-of-state, owing to ongoing ripple effects from the 2005 Granholm v Heald ruling by SCOTUS (544 U.S. 460).

However, we were perfectly free to create terms of engagement for prospective BIG brewery members, and did. They still include this qualifier: “All critical phases of the beer making process (must) occur within the state of Indiana.”

You’re probably wondering why it mattered, and what was to be gained from excluding Granite City (as well as future “breweries” organized in like fashion) from the happy Hoosier brewing family.

For one, the board had conducted an informal survey of members, and the gist of the sentiments received in reply was that Indiana brewers, from the biggest (Three Floyds) down to the smallest backroom nano, were overwhelmingly united in favor of adhering to the traditional integrity of the brewing process, and emphasizing the expertise required of this process as helping to affix a fundamental point of distinction between a brewery making its own beer, and a multi-tap or beer bar selling someone else’s.

Want the equity? Then pay your dues.

As such, member breweries felt strongly that the playing field should be level, seeing as members benefited from BIG’s informational, promotional and Indiana-centric legislative outreach (especially the latter). Granite City’s Fermentus Interruptus™ was viewed as a gimmick that undercut the ethos of “craft” brewing (I know; whatever THAT is defined as), and perhaps worst, a cost-cutting compromise that might be seen as tarring all breweries with the same brush.

Are these conclusions debatable?

Of course they are. That’s the overarching point of telling this story. Debate and discuss; have at it, preferably in the company of a beer.

Current relevance is another matter, and I have no idea if the situation has changed since I left the board in 2016; the pandemic has come and gone, the mighty tide of Hoosier brewery openings has ebbed, and Granite City is down to one location in the state.

All this aside, you’ll be unsurprised to learn that my personal view about the topic of Fermentus Interruptus™ is more nuanced.

From Granite City’s perspective as a chain food and drink concept devoted to multiplying its outlets, prime consideration must be given to having its dishes and beers taste the same wherever they’re consumed. So be it. Soviet communism viewed dumplings from a similar vantage point for its own reasons, and that’s fine by me — but let the buyer beware (in all transactions, not only this one).

However, there’s another side to it. I’ll illustrate this by using the example of a hypothetical Indiana on-premise food and drink establishment in planning, one wishing to expand the perimeter of craft beer in its hometown, and reaching the conclusion that “we want to brew beer.”

That’s admirable. Just know that nothing good comes easy. If it’s a brewery you want to be, then be a brewery. Set up the system (without the stop sign), learn to use it or find someone who knows the ropes, and get going.

Know that you’re entering a realm of mystery and imagination composed of equal parts white-coated chemistry lab minions and bearded drunken gnomes in a dark forest hoisting tankards and slurring gibberish.

Which is to say, successful brewing demands proficiency in both science and art. While there is nothing illegal or unethical about doing business with a “central wort house” (a phrase that increasingly strikes me as peak Orwellian), I believe that to “brew” this way is to miss something critically important about the nature and practice of the beer game we’ve all been playing.

It’s best when it comes from your heart and mind, not someone else’s wort workshop.

Sales pitches from wort vendors (“pennies per pint” or “no brewing experience necessary”) strike me as pernicious, but they actually hint at the fundamental question that must be answered before money changes hands: What does a business-in-planning really want to be, and is small-scale brewing the best (or only) way to be it — or are there other ways?

To repeat, if one wishes to brew, then brew.

Concurrently, there are alternative strategies for ramping up to full-scale brewing, one of which has an added benefit of tying the existing brewing community together by means of shared purpose: Work with an existing brewery to achieve your vision.

The hypothetical establishment used here as an example might contract with an existing Indiana brewer who possesses excess production capacity, for instance creating two flagship house beers to unique specs, preferably lower-gravity styles calculated to sell quickly as sessionable mainstays.*

In addition to its house beers, the Indiana establishment would have other draft lines and pour guest beers, positioning its bespoke house beers as the ones available nowhere else, and intelligently arranging guest drafts to help reinforce the primacy of house beers, while still moving briskly themselves.

Yes, it is true that the establishment would be relying on the continued health and well-being of the contract brewer, but that’s no different than pursuing an arrangement with a “central wort house” (or suppliers of any sort; contracts aside, guarantees in life are scant).

Yes, I know, in this scenario someone else is still doing the brewing, but at least someone else is doing all of the brewing, and opportunities for community-building and cross promotions are rampant with existing and experienced brewers. Establish those two beers, then commission another. At some point, take it up a notch with your own small brewing system.

Either way, strive always to think your beer program and to weave it together to be unlike the others, springing from the mind and design of the establishment’s ownership, rather than someone else’s default recipes or a wholesaler’s self-interest.

How do we know when beer is real and unalloyed, when it’s more than calorie counts and Stupor Boll ads? How do we sense the pride and craftsmanship that goes into brewing a great beer? Do you ever get the feeling when entering a brewery — new or old, small or large — that it’s like walking into a cathedral, because drinking a particular beer is more than a fleeting financial transaction but a life-defining sacrament.

Isn’t that the best thing ever?

I’ve felt it, although after all these years it remains difficult for me to define exactly how this jumble of thoughts and emotions come together. It’s easier to tell when they don’t, and to me, that’s the true meaning of Fermentus Interruptus™.

—

* The recent Parlour Pizza/Falls City Brewing marriage is somewhat analogous, joining a brewery in need of higher sales with a pizzeria possessing multiple “tap rooms,” not merely one, in effect making Falls City’s brands into Parlour’s house beers.

—

Previously at Hip Hops:

Hip Hops: About non-alcoholic beers, and what they’re missing (or not)

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 42 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 42 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.