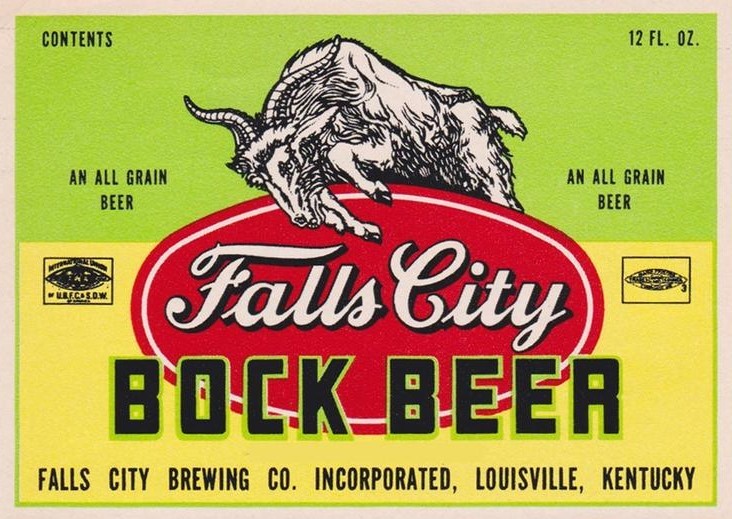

As previously noted at F&D, you can “goat” for broke at the annual NuLu Bock and Wurst Fest, which takes up most of the day on Saturday, March 23. Meanwhile, your beer columnist’s favorite locally-brewed, fundamentally honest, old-school Bock comes from Falls City. Accordingly, brewer Cameron Finnis tells me that he has sent a few kegs of Bock out for distribution, and of course it’s also on tap at the newest location of Parlour Pizza (Falls City’s ex-taproom), adjacent to the brewery at 901 E. Liberty. The following is a lightly edited repeat, and remember: You might dye a Maibock green, but why on earth would you want to?

As previously noted at F&D, you can “goat” for broke at the annual NuLu Bock and Wurst Fest, which takes up most of the day on Saturday, March 23. Meanwhile, your beer columnist’s favorite locally-brewed, fundamentally honest, old-school Bock comes from Falls City. Accordingly, brewer Cameron Finnis tells me that he has sent a few kegs of Bock out for distribution, and of course it’s also on tap at the newest location of Parlour Pizza (Falls City’s ex-taproom), adjacent to the brewery at 901 E. Liberty. The following is a lightly edited repeat, and remember: You might dye a Maibock green, but why on earth would you want to?

—

Is Bock the G.O.A.T.? This question has been nagging me since Jimmy Carter was in office.

All I knew for sure at the time was that Bock beers were dark, and they appeared each year in spring.

It was the 1970s, the decade when America’s beer scene reached its very nadir, increasingly awash in ever-lighter oceans of Pilsner pretenders, and with fewer than 100 independent breweries still operational in the entire country (in 2024, the number approaches 10,000).

On the coasts and in a handful of other locales nationally (Denver and environs, and to an extent the Upper Midwest), the stage was being set for a revival, although it took a while for this future hope to become tangible — and for us to get a bit older in order to properly appreciate it.

But even as an underaged beer scrounger (at least until 3 August 1981), I was well aware of the customary springtime Bock release schedule, as upheld by a few of the remaining breweries of German descent. Only three of these brands stick in my palate: Huber and Augsburger (Wisconsin) and Stroh’s (Detroit). There were others, but my beer recall isn’t total any longer.

The old guys drinking lunch referred to Bock as a tradition, which seemed plausible, even if the exact reason largely eluded beer drinkers in my neck of the Hoosier woods. Reliable knowledge about beer styles and seasonal brewing was scant, and Bock’s coppery brown color engendered even more confusion, because most beers were golden — pale as Bunny Bread, canned, ice-cold, and available year-round for plucking from the cooler at the nearest package store.

Bock definitely was different. Why was that, anyway?

Just as ancient cultures conjured supernatural explanations for otherwise inexplicable natural phenomena, our befuddled elders labored to explain why Bock beer was dark when “regular” beer wasn’t, eventually contriving a satisfactory mythology to the effect that Bock took on the color of the grimy residue produced during annual scrubbings of the brewery’s vats.

Although I’d moved past the point of believing in organized religion or the stork as bearer of newly minted babies, there remained gullible innocence in fermentable affairs, and I blithely accepted these flailing assertions, until blessedly, the Beer Hunter undertook to intervene.

When the late, great beer writer Michael Jackson’s seminal beer books began washing ashore on the banks of the Ohio, finally the conceptual fog dissipated. I subsequently grew to beer-turity clutching these dog-eared guides as secular scripture, exactly like so many others who were coming to accept Jackson as their preferred chaperone in pursuit of the perfect pint.

He didn’t let us down.

Significantly, Jackson provided far more than photos and raw, fleeting facts about beer. Rather, he told stories about beer. Almost four decades later, many of these stories remain staples of my performance shtick and salesmanship, leading to a strong personal belief in storytelling as an essential component of beer appreciation, as opposed to the intrinsic laziness of Untappd.

Fashions change, but hardcore lore remains, and Bock’s seasonal tale is a particularly compelling variation on a storied theme. All the narrative elements are here, from holy water and animal husbandry to weather forecasting, and some of them might actually be true.

For instance, what’s not to like about monks brewing beer?

Elements of Bock-think originated inside the mysterious monastic breweries of Central Europe, where the rigors of self-denial (Lenten or year-round) did not preclude consumption of malty, sweet and excessively caloric “liquid bread” (writer Mark Dredge suggests a “feasting” variant of the usual monkish fasting story, here).

Reformation didn’t close these dietary loopholes, although Napoleon was literally hellish on monasteries and their privileges.

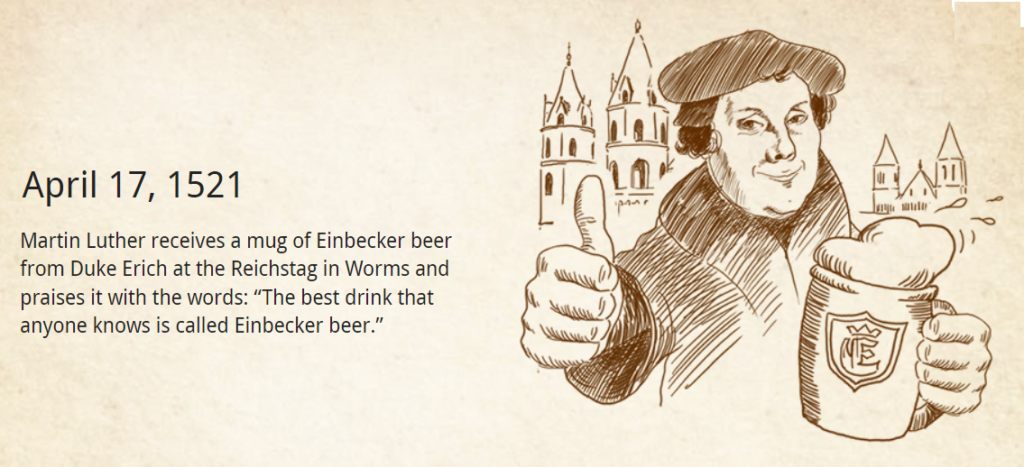

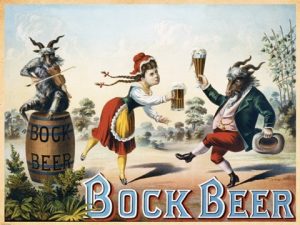

There are domesticated ruminants, too. The name “Bock” probably represents a guttural corruption of the ending syllable of the German town called Einbeck (“beck” mutating into “bock”), but eventually the word Bock fused in the Bavarian popular imagination with a vernacular term for goat, hence the beer label symbolism handed down to us through the ages.

Accordingly, local writer Kevin Gibson tells one of my favorite local Bock tales in his book, Louisville Beer: Derby City History on Draft. It recounts the pre-prohibition Louisville institution of Bock Day, which was a much anticipated springtime revel.

Henry Caldwell and Mary Smith were drinking on March 18, 1894. The couple apparently enjoyed several bock beers that day, according to a police account, and decided to make a living, breathing bock beer sign to celebrate their enthusiasm for Bock Day. However, as they couldn’t find a goat, they instead stole a pig and apparently tried to paint the poor animal into a sign near the corner of Ninth and Walnut Streets.

“The beast objected loudly,” according to the report, “and disturbed the services of the church near by. Officers McPeak and Hessian arrested all three. The pig was sent to the West End pound, and the man and woman to the station house. They told different stories about how they came into possession of the pig.” One wonders if the police officers themselves had hoisted a few bocks that day, given that they arrested a pig.

But these sorts of stories were common finds in my research into Bock Day in Louisville. From mudball fights to broken windows and hatchet attacks, it seems that the long winter of drinking lighter beers and lingering indoors left many Louisvillians unprepared for the punch in the brain that the bock brought with it.

Bock effectively illustrates a rich cross-section of Old World cultural tapestry. It’s a seasonal habit of thought, one redolent of Munich and Bavarian environs, migrating with immigrants who were settling far away in a New World.

As the final cold gusts of winter recede, and spring’s stirrings draw tantalizingly near, it is time for Bock: A rich, deep, chestnut-colored lager of higher than average strength, served in impossibly huge steins, designed to lure the timid from dens of placid hibernation beside fiery hearths, and back out into chilly outdoors beer gardens, all the better to prepare for days growing steadily longer and a new planting season just around the corner.

The Bock story doesn’t end in the foothills of the Alps. Three hours north of Munich in rural Franconia, various forms of Bock, some of them pale in color, still are brewed for release before Christmas, not Easter. Few of these make their way outside the region, although the word “Bock” itself has been known to travel widely.

The Bock story doesn’t end in the foothills of the Alps. Three hours north of Munich in rural Franconia, various forms of Bock, some of them pale in color, still are brewed for release before Christmas, not Easter. Few of these make their way outside the region, although the word “Bock” itself has been known to travel widely.

Portugal boasts a beer favored by generations of spirited visiting English football fans, at least some of them well-behaved: Super Bock, which is neither super, nor remotely resembling classic Bock. The same strange distinction applies to the curiously passive, flavorless Texan anomaly called Shiner Bock.

Meanwhile, Doppelbock is the imported German style most often spied on store shelves hereabouts; Celebrator, Paulaner and Optimator are famous names, and they’re certainly stronger than “single” Bock, though never precisely double the strength – unless you classify Austrian-brewed Samichlaus as Doppelbock.

The famous Schneider brewery in Kelheim, Bavaria brews Aventinus, a delicious Weizen (wheat) Doppelbock, and in a trick predating distillation often practiced in northern climes, Schneider also freezes the Aventinus, removing the frozen water and selling the concentrated, stronger finished product as Eisbock – once a specialty of brewers in the town of Kulmbach.

The famous Schneider brewery in Kelheim, Bavaria brews Aventinus, a delicious Weizen (wheat) Doppelbock, and in a trick predating distillation often practiced in northern climes, Schneider also freezes the Aventinus, removing the frozen water and selling the concentrated, stronger finished product as Eisbock – once a specialty of brewers in the town of Kulmbach.

And, returning to the dark color of most Bocks (Maibock is an exception), brewers clean their equipment daily, constantly and compulsively; spring cleanings with steel wool are bunk.

Rather, when barley is malted, it is finished by kilning, resulting in different shadings and flavor characteristics, all of them waiting to be combined by the clever brewer to achieve a chosen stylistic end. Additions of Vienna, Caramel and/or various specialty malts produce Bock’s alluring hue.

These are my own Bock stories, and I’m sticking with them.

Precise details are less important than a closet romantic’s dreams of roasted pork, church steeples, radishes, children running between heavy wooden tables, grizzled and mustachioed men in lederhosen with wives garbed in dirndls, and foaming mugs of malty dark beer dispensed from barrels stacked like cordwood on countertops.

A picture still may be worth a thousand words, but my imagination is exponential. Jackson’s sadly gone, and while beer storytelling isn’t dead, it has undergone a certain devaluation. These days, beer enthusiasm often is expressed with a throwaway brevity, one defying depth of feeling; mile-wide and inches deep, it thrives on social media, where broad exposure inexorably minimizes purity of context. Beer lovers check in, tweet, post and rate. They don’t tell enough stories.

Still, stories and beer go quite well together. We need more of both.

—

Previously at Hip Hops:

Hip Hops: Erin Go Blagh 2024, a much needed St. Paddy’s Day etiquette primer

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 42 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 42 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.