We all have two sides. The one we let people see and the one we don’t.

We all have two sides. The one we let people see and the one we don’t.

During my college days I enjoyed a well-deserved reputation for dissipation, as often shared with my old friend Bob. The ancient Egyptians might have been paid in beer to construct the pyramids, but I paid for beer in order to receive a degree in philosophy.

One day the two of us were seated in the university commons area, no doubt plotting our next drinking escapade, when we were approached by a classmate brandishing papers. These proved to be lists of facts about alcoholism, accompanied by one of those familiar surveys encouraging the reader to answer 15 questions about drinking, then flip the sheet to learn what the answers implied.

(The scene is ironic, though only in retrospect. She went on to have a career in the field of alcohol and drug “prevention,” while I kept drinking beer and eventually figured out a way to be remunerated for it.)

The survey was “yes or no,” and Bob and I followed the instructions, answering two-thirds of the questions “yes.” The remainder didn’t apply; neither of us had jobs at the time, so “does drinking cause you to miss work” had to be tossed.

The verdict was predictable: One “yes” meant extreme caution about alcohol was merited, two that doom was right there on the horizon, and three — well, call for an ambulance and a priest.

You may extrapolate from this anecdote that I don’t take alcoholism seriously. This isn’t true, and I do, even if I’m prepared to argue that the survey from long ago was utterly bogus. I’ve spent a great deal of time these past 40 years in proximity of heavy drinkers, and at various stages I’ve been one myself.

In my dotage, I’m drinking less than at any time since junior high school, and through no conscious effort. Over a long period of time, my consumption has plummeted, and I’ve invested the savings in food. I enjoy a drink or two here and there, mostly beer, and quite seldom allow it to slide down the slippery slope to “too much.”

Are my proclivities still there, waiting to be aroused? I don’t know, but at the moment drunkenness holds no appeal for me.

I do understand what alcoholism means, while remaining opposed to prohibitionist sentiments, and yet concede to speculating on occasion whether there is a flip side to “Bourbonism,” distilled spirits being a class of alcoholic beverage that interests me far less than beer or even wine.

Consider the following “equal time.” It’s a review from 2013, previously published at my now defunct blog. Is there a discussion waiting to be had? If so, let me know.

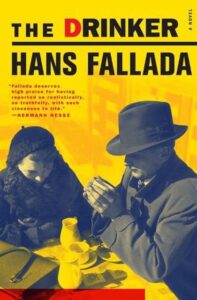

“The Drinker,” by Hans Fallada (a book review)

A respectable 40-year-old businessman returns home from a normal workday to discover the maid has neglected to replace a floor mat by the front door. Annoyed at the omission, he tracks mud into the entryway, is mildly chided by his wife, and becomes uncharacteristically angered.

A short time later, he suddenly recalls the existence of a long-forgotten, stale and vinegary bottle of red wine stashed in the cellar. Although a virtual teetotaler, a glass of this rancid wine helps considerably to take the edge off his day, and he feels far better. The floor mat spat now forgotten, he gifts his wife with money to buy herself something special, and goes to bed.

Next thing we know, his permanent residence is an insane asylum.

—

For Americans of a certain age, to read Hans Fallada’s novel The Drinker is to immediately recall an episode of The Simpsons, wherein a flashback depicts Barney’s very first drink of beer as a young man, as offered to him by Homer. With one swallow, the well-groomed and sober young preppie morphs immediately into a swollen, drunken slob.

A similar downward trajectory awaits Fallada’s main character, Herr Sommer — and there is very little humorous about an amazingly detailed and poetically rendered descent into lunacy. However, the story of The Drinker doesn’t end with a gripping, frightening novel, because the circumstances surrounding Fallada’s work of fiction hardly were imaginary at the time of writing.

Hans Fallada’s real name was Rudolf Wilhelm Friedrich Ditzen. He was born in Greifswald, Germany in 1893, and died in Berlin in 1947. In 1944, with World War II still raging throughout the continent, Fallada managed to write The Drinker in two weeks flat while incarcerated in an insane asylum. It would have been an incredible feat anytime and anywhere, much less one undertaken secretively in an institution run by the Nazis, who obviously were unbound by the inhibitions of Hippocratic oaths.

In fact, Fallada’s entire life was difficult. A severe injury to his head during adolescence seemed to have changed him, perhaps leading to lifelong mental health issues, suicide attempts and drug addiction, and yet, in that strange way sometimes characterizing an artist’s process of creation, Fallada became an exceptionally gifted writer prone to frenetic periods of work activity followed by elongated spirals into madness.

During the 1920s, Fallada married and enjoyed an extended period of domestic harmony and commercial success, including a worldwide readership for his novel, Little Man, What Now? But a collision course with Hitler’s totalitarian regime was inevitable owing to its inclination to funnel all manifestations of art into approved channels of support for the regime.

The storm clouds gathered, and yet Fallada chose to remain in Germany and not seek exile, spending the war years walking a tightrope — neither an overt collaborator, nor seeking involvement with the resistance. From our vantage point these many years later, cohabitation with repression does not seem the ideal path for a writer with only a fragile grip on sanity, who already was peering into the abyss with clocklike frequency.

Fallada tried waiting it out. Perhaps the pressures hastened his demise, but maybe the die had been cast long before.

—

Does Fallada’s wartime work as a writer represent acquiescence with the various Goebbels party lines, or was he endeavoring to write between them? The debate persists to this day. Was The Drinker allegorical, suggesting the common man’s struggle to cope with oppression? Or, was it an autobiographical work so meticulously researched from personal experience that larger themes aren’t really necessary?

Of course, it’s up to the reader to decide.

Getting through The Drinker is like watching a cat torture a mouse before killing it. As the pages turn, Herr Sommer’s layers of dysfunction are unsparingly peeled away by the first-person narrative, and the deep-seated rot exposed. It becomes clear that none of the character’s many difficulties originate with that first drink of wine; rather, the alcohol merely delineates them.

Sommer already has started losing grip of his business, and growing apart from his wife, whom he resents for being efficient when he is anything but. The lies and self-deceptions merely require readily available fuel to combust into elephantine self-destructive proportions, and bottles of schnapps and cognac consumed with the speed that most of us reserve for ice water after a hot afternoon in the garden couldn’t be better for ignition.

When describing the weeks-long binge embarked upon by Sommer, Fallada’s prose is hazy and replete with confusion, self-loathing and false bravado, but when he lands in jail and begins drying out, matters become quite clinical. Eventually transferred to the asylum to receive the “help” he quite clearly needs, the inmate offers a portrait of daily life there that is detached, detailed and thoroughly horrendous.

There are no Hollywood-style happy endings to The Drinker, a novel that I recommend unreservedly, although not without certain caveats: If you’ve ever wondered whether your most recent drink was one too many, owing not to ordinary intoxication but to extraordinary curiosity as to whether there might come a point when the altered state persists even after the alcohol’s all gone — well, Fallada’s tale might not be an easy read for you.

It wasn’t easy for me, and I’ll probably be skipping Happy Hour today.

Previously at “Hip Hops”:

Hip Hops: Death, taxes, generational discord – and a few well-chosen beers in one’s dotage

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with