Edibles & Potables is here for you, engine idling at the intersection of humility and offal. An explanation is needed, and we can always rely on Madonna to jump-start the conversation.

“Ultimately it boils down to the same thing all relationships boil down to: eating humble pie. I sometimes eat quite a lot,” she said. “But, however bitter it might taste, it’s the best pie. It’s on the menu constantly for both parties.”

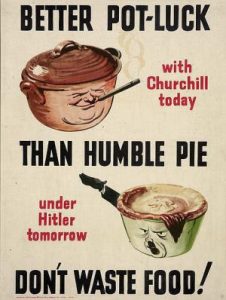

To eat humble pie is to admit you’ve been wrong, to be apologetic, or to accept defeat, which presumably accounts for the bitter taste. As such idioms go, Americans tend to “eat crow,” while the British more often refer to ingesting humble pie.

To a certain (shall we say, “older”) generation, Humble Pie has a very different meaning, and a doctor may or may not be required.

Given the unfashionability of meat pies, the culinary aspect of humble pie may come as a mild surprise.

In the 14th century, the numbles (or noumbles, nomblys, noubles) was the name given to the heart, liver, entrails etc. of animals, especially of deer – what we now call offal, or lights. By the 15th century this had migrated to umbles, although the words co-existed for some time. There are many references to both words in Old English and Middle English texts from 1330 onward. Umbles were used as an ingredient in pies, although the first record of ‘umble pie’ in print is as late as the 17th century.

When it comes to baking a savory pie containing the “meaty parts of a beast’s pluck – the heart, liver, kidneys and lungs,” the word numbles first mutated into umble, then humble.

This is where it gets confusing, because the idiomatic meaning of eating humble pie references humility, not offal, and the word humble (submissive, respectful, lowly in manner, modest, not self-asserting, obedient) has an entirely different etymology.

There is an often-repeated suggestion that Umbles were lower-class foods, so anyone who ate a pie of them was a humble and inferior person. This sounds plausible today, when we disdain offal and sell it off cheap, but kidneys, tripe and the rest were sometimes thought to be amongst the most prized bits – as you can see from the receipts (recipes) here which adorn them with costly spices way beyond the reach of the humble.

And here is one of the recipes.

Original Receipt in ‘The Country Housewife and Lady’s Director‘ by Prof. R Bradley, 1728 (Bradley 1728)

To make Umble Pye. From Mr. Thomas Fletcher of Norwich.

Take the Umbles of a Deer and boil them tenderly, and when they are cold, chop them as small as Meat for minc’d Pyes, and shred to them as much Beef-Suet, six large Apples, half a Pound of Sugar, a Pound of Currans, a little Salt, and as much Cloves, Nutmeg and Pepper powder’d as you see convenient; then mix them well together, and when they are put into the Paste, pour in half a Pint of Sack, the Juice of two Lemons and an Orange: and when this is done, close the Pye, and when it is baked, serve it hot to the Table.

Take the Umbles of a Deer and boil them tenderly, and when they are cold, chop them as small as Meat for minc’d Pyes, and shred to them as much Beef-Suet, six large Apples, half a Pound of Sugar, a Pound of Currans, a little Salt, and as much Cloves, Nutmeg and Pepper powder’d as you see convenient; then mix them well together, and when they are put into the Paste, pour in half a Pint of Sack, the Juice of two Lemons and an Orange: and when this is done, close the Pye, and when it is baked, serve it hot to the Table.

I know more than a few deer hunters, and recommend they pay heed. Eating humble pie needn’t mean what you think it does, and by the way, should you attempt the above recipe, dry sherry probably will substitute capably for the Pint of Sack. Just let me know how humble pie tastes, because I’ve become a pescatarian, and it’s stargazy pie or bust for me.

Cover photo: I’m exiting a pub in Yorkshire in 2001. There was no humble pie, but the cask-conditioned ale was stellar.