It’s July 4, and you’re celebrating the nation’s Independence Day holiday. Meanwhile in northeastern Spain amid the former Kingdom of Navarra, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused the Fiesta de San Fermin in Pamplona to be canceled for the second year running. I attended San Fermin on four occasions prior to the advent of smart phones, for which I’m suitably grateful; what happens at San Fermin definitely is better off staying there. My account here was written in 1995, and has been revised several times since.

—

I cannot imagine any European urban tableau that matches the annual Festival of San Fermin (July 6 through 14) in Pamplona, Spain. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 probably packed more of a punch, but it was a one-off celebration that required almost three decades of preparation, while in Pamplona, they do it every year.

In ascending order of intensity, I’ve witnessed a May Day parade in Vienna, Munich’s fabled Oktoberfest and a random Greek political rally in the city of Patras, and none of these events so much as approach the multi-faceted lunacy of San Fermin.

Pamplona’s distinctive strain of craziness is a fascinating hybrid. Spectacular public displays of orgiastic, besotted and scatological indecency occur alongside demonstrations of a proud and dignified adherence to traditional values that extend too far back into time to be completely understood.

San Fermin is a primitive, almost mythological celebration expressed through a daily, seemingly disparate, combination of elements. Confrontations between man and bull, gatherings of grandparents and grandchildren to share hot chocolate, outpourings of religious conviction, incessant marching musical mayhem and extraordinary alcoholic lubrication all suffice for snapshots during festival days.

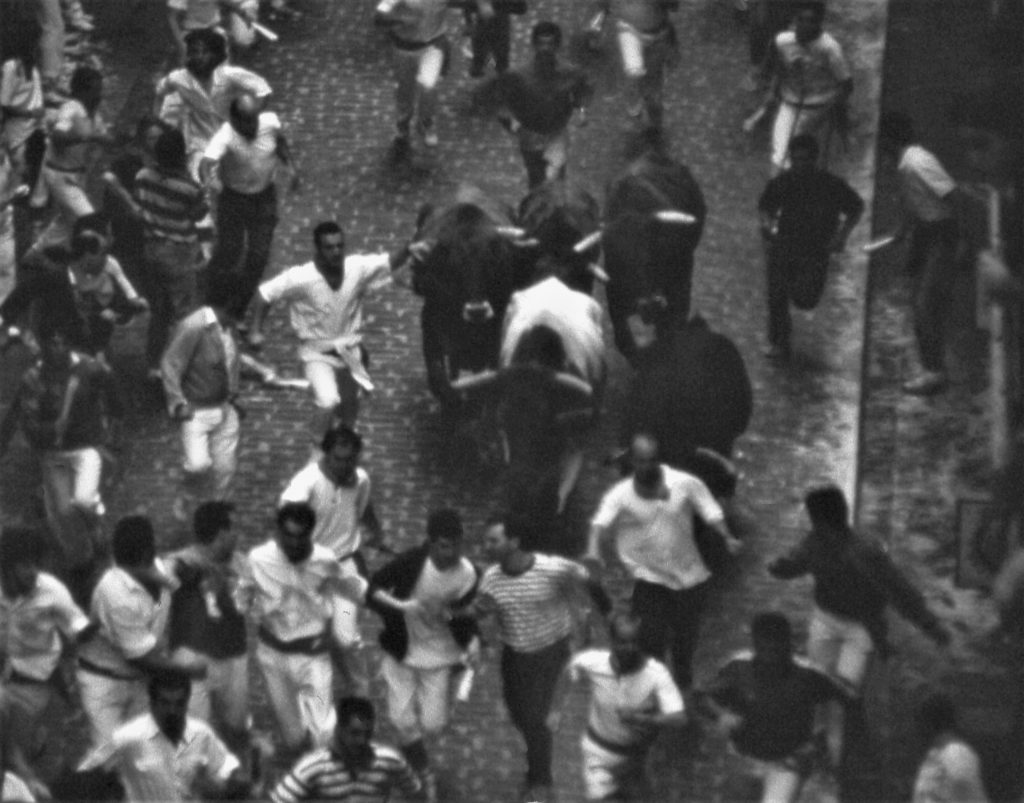

The morning hours provide the first shock to those visitors craving normality, as huge beasts and eager humans take to the streets of Pamplona in a bid to memorialize the death of the festival’s namesake patron saint, martyred by being dragged through the street by a bull.

Trouser Stains and Pavement Burns.

One thing is for certain. The greatest two minutes in sports do not take place at Churchill Downs each May.

The greatest two minutes – well, “few” minutes – in sports is Pamplona’s “Running of the Bulls,” which takes place each morning for eight days during San Fermin.

The six bulls to be featured in the evening’s bullfight, accompanied by six horned heifers for a total of twelve, are released into barricaded streets and driven 900 meters (a little more than half a mile) to their pens in the bull ring. In the path of the bulls are hundreds, perhaps thousands, of thrill-seeking festival-goers.

Some actually are sober.

For many of the true believers, the run each morning is a quasi-mystical experience that metaphorically represents mankind’s most primitive fears and primal urges, now buried in our collective subconscious, and brought to the surface during the mad daily race through the streets.

Other runners are simply unconscious, having been consumed, digested and expelled by the singular intensity and alcoholic promiscuity of the festival that never sleeps.

Late each evening, as the throngs of human celebrants eat and drink, and marching bands lead impromptu parades down the narrow streets past dancing and sleeping revelers, the following morning’s bulls are led to pens at the foot of street called Cuesta de Santo Domingo.

Early in the morning, workers begin assembling the barricades – wooden beams the size of railroad ties set into existing posts – that enclose the route of the running: Santo Domingo, into the small Plaza Consistorial, then a left turn onto Carrer Mercaderes, followed by a very hard right onto Carrer Estafeta.

The street called Estafeta accounts for roughly half the distance of the run, and it leads directly to the Plaza de Toros and the entrance to the bullring itself.

The hard right turn from Mercaderes onto Estafeta is the scene of many brutal collisions between man and beast (and, far more often, man and man). The bulls often crash headlong into the particularly sturdy barrier erected at this turn before righting themselves to charge up the extremely narrow Estafeta straightaway, where numerous alcoves, waist-high windows and recessed doorways tempt the runners with visions of safe haven.

At about 7:30 a.m., cordons of police begin moving people – some asleep, some awake – from the route of the run. Once the human debris has been cleared, sanitation workers swiftly remove the piles of festival trash, sweep down the asphalt and scatter sawdust on the urine slicks that are an ever-present feature, both visually and aromatically, of a festival where many people drink and few bother with the few portable WCs.

The viewpoint of the bulls can never be known, but the human participants in the run generally can be readily divided into two groups. The vast majority wishes for nothing more than to be able to return home and tell their friends that they “ran with the bulls.”

The remainder, including both native purists and foreign aficionados, really want to run with the bulls, to run near the bulls, ahead of the powerful animals or alongside them, and to inject an element of strategy into what is essentially a scary business for all involved.

In order to separate the two groups, and to account for the large numbers of runners involved, two waves of runners are sent to a starting position on Estafeta that is at least 2/3 of the way through the course. Thus, the masses are permitted to jog a few yards into the bullring and declare victory, and the crowd is reduced somewhat for the benefit of the more diligent.

Thus at 8:00 a.m. begins the greatest few minutes in sports, when a rocket explodes, signaling the release of the bulls from their pens. A second rocket sounds almost immediately, indicating that all the animals are off and running.

The bulls are driven by expert native runners, who wield canes and will use them if necessary – not on the bulls, but to lash runners who attempt to touch the bulls or create problems that might lead to the animals becoming separated.

As long as the bulls are together, at least loosely grouped and charging forward, the run is fairly smooth and the greatest number of injuries occur as a result of humans falling over one another. The situation can turn considerably nastier if a bull becomes separated. It is only then that these massive animals become truly annoyed and begin charging people with the object of ramming, goring and tossing them across the street with a flick of the head.

There have been at least a baker’s dozen fatalities since the 1920s, and serious injuries are recorded each year. It is said that three of the deaths came on one day when a group seeking safety in an Estafeta doorway was cornered by a single bull.

Still, when all factors are considered, running with the bulls probably isn’t any more hazardous than walking down a sidewalk in America, near drivers busy gazing at their mobile devices, chomping on Rallyburgers or applying their makeup as they ignore the proper navigation of their oversized vehicles, all of which is at least as potentially harmful as carefully bred, half-ton fighting bulls.

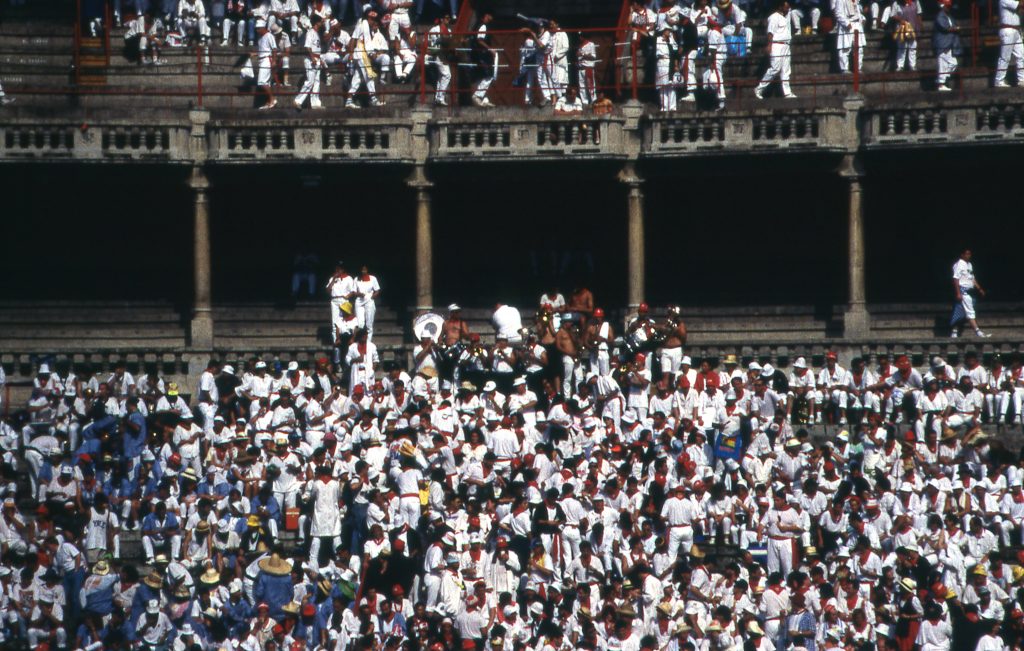

The running ends at the bullring. The bulls are driven into their pens to await their participation in the evening’s ritualistic bullfight, and triumphant “runners” mills around the ring. Many more of them party in the stands. At intervals, heifers with sawed-off or padded horns are sent into the ring to wreak havoc among the drunken mass of exhilarated humanity.

Meanwhile, the aficionados are entirely absent, having already adjourned to bars like the Txoko on the Plaza de Castillo for chilled champagne and lengthy post-run analysis.

Sleeping’s Just Another Word for Nothing Left to Drink.

There is no beginning or end to anything during San Fermin, with nothing to compare to the absolute certainty that is experienced during Oktoberfest in Munich, when the powers that be say it’s time to go, RIGHT NOW, and the whole jam-packed fest ground disperses well before midnight.

However, for the sake of the narrative, I’ll say that a festival day in Pamplona begins with the running of the bulls and subsequent festivities (drinks and a light breakfast at a bar or coffee shop), continues through daylight hours filled with music, dancing, religious processions and endless partying opportunities, pauses (maybe) for some semblance of a siesta or brief nap in mid-afternoon, slows again as the early evening bullfight is held (always ending before dark, as there are no lights), then spills out onto the streets in its raucous immensity for eating, drinking and related activities until around midnight, when the nightly fireworks display announces the (end? beginning?), and people begin to consider going somewhere to eat their evening meal.

At some indefinable point shortly thereafter, everything dissolves into alcohol-driven chaos and one begins to see the sleeping bags tossed on any green spot not yet taken – or urinated atop.

San Fermin’s credentials as a world-class party are indisputable and enduring, and yet it should be noted that despite everything so thoroughly adult and often wretchedly dissipated about the eight-day marathon, at heart it remains an oversized family festival.

Once I was in the Plaza Consistorial when the parade of the Gigantes (giant puppets representing different facets of the Pamplona experience) passed through, dazzling everyone present, but especially captivating the children, who were being energetically photographed and videotaped by their indulgent and equally excited parents.

Children in the official San Fermin uniform of white shirts and red scarves are everywhere, and their special milieu somehow co-exists with that of the Euro Trash Party Nation occupying Pamplona for the celebration. Co-existence like this probably couldn’t happen in America, but apart from occasional lapses it seems to work fine in Pamplona. Just don’t ask me how.

Good food is available in abundance during the festival. One time I picnicked in the comfortable shade of the trees in the park along the old town walls, and on another occasion indulged in still more fresh bread, chorizo (spicy salami), anchovy-stuffed olives and thin, pepperoncini-like peppers while watching an Andalucian troupe perform traditional song and dance near the Citadel, an old fortress upon whose grounds camped many of the younger celebrants.

Thanks to the discerning selections of my cousin Donald Barry and his friends, I’ve enjoyed several outstanding restaurant meals during San Fermin. Once we were fortunate to be seated next to an articulate, multilingual teacher who gamely attempted to explain the symbolic significance of the festival, the running and the bullfight. As this gentleman spoke, he made short work of fried trout stuffed with ham, a Basque specialty of the Pyrenees Mountains astride the nearby border with France.

Separating the Basque themes from the Spanish in this intermixed sector of the planet is a fool’s errand far exceeding my purposes at present, but allow me to observe that one of my favorite ever meals during San Fermin came at a Basque social club, formerly the home base of an extreme-left offshoot of the ETA separatist movement, where we were taken to dine by American veterans of Pamplona’s annual party wars.

The entrance was an open storefront where beer and snacks were being sold to passers-by. Behind it were several big partitions like those used in classrooms and offices, which bore inconspicuous, hand-lettered sheets of paper that announced the presence of the eatery behind the partitions, where communal tables sagged beneath the weight of steaming cauldrons of stew and salad platters.

There and elsewhere, we were greeted by ample portions of mixed green salads with onions, tomatoes, black olives and tuna, white bean soup, ever-present baskets of crusty bread, hearty red wine, bacalao (dried, salted cod cooked in tomato sauce), and bull stew (rich beef stew purportedly containing the meat harvested from the previous day’s fighting bulls.

Alcohol in varying forms was freely consumed, emphasizing wine, cognac and champagne, but also quite a lot of beer. The latter is my life’s work, hence a digression.

The Beer in Spain Comes Mainly Plain.

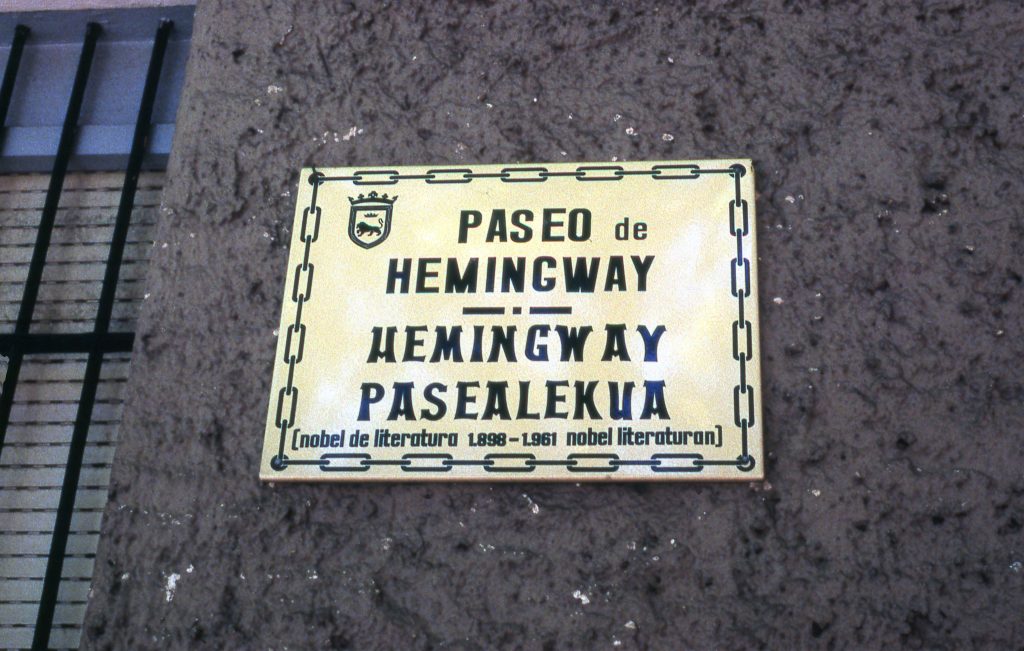

Ernest Hemingway wrote about Spanish beer in the glossary to his book about bullfighting, Death in the Afternoon:

“Cerveza … draft beer … is served in pint glasses called dobles or in half-pint glasses called canas, canitas or medias. The Madrid breweries were founded by Germans and the beer is the best anywhere on the continent outside of Germany and Czecho-Slovakia … in Pamplona the finest beer is at the Cafe Kutz and the Cafe Iruna. The beer at the other cafes cannot be recommended.”

Um, how to say this? Hemingway was not a beer writer. For those accustomed to diversity, only a few Pamplona cafes can be recommended, although Irish ales like Guinness, Kilkenny and European lagers are increasingly available.

(Editor’s 2021 note: In the two decades elapsing since my most recent visit to Spain, the beer situation has changed drastically. Craft beer and its variants now flourish alongside a significant craft cider segment. I suspect lager is as yet the people’s choice, and yet there are other options now).

San Miguel, Mahou, Aguila and Estrella are the most commonly seen Spanish beers. All are mild, golden lagers; none have sufficient hop bite to justify status as pilsners. While in Pamplona, I’ve chosen San Miguel most often, both in bottles and on draft. It is malty and almost sweet, with just enough of a dry finish to avoid being cloying.

Each of the four mentioned above brews a lager of higher alcohol content (in the range of 5.5 – 6.5% by volume) that might be characterized as a Dortmunder/Export style. I tried one of them, Aguila’s Master, and found it to be a fuller-bodied improvement over regular Aguila. Unfortunately, only the everyday lagers generally are found on draft in Spain, and the best that can be said of them is that they fill their limited purpose capably, quenching one’s thirst on a hot day.

Life and Death in the Bull Ring.

One time in Pamplona for San Fermin, I was left to fend for myself on a day when all my friends were in attendance at the bullfight. I walked for twenty minutes toward the outskirts and stopped into a relatively peaceful neighborhood bar for beer and tapas (regionally referred to as pintxo or pincho).

Fortunately, the bullfight was being televised, so I sat down to watch two of the six bulls and study the dynamics of the event. Perhaps owing to books like Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises and James Michener’s Iberia, I was fascinated and eager to go to the bullring, as we’d be doing the following evening. Watching on TV helped me to understand the basics.

The morning of my bullfight day began with observing the run, and drinking began early at the Windsor, where many of the American aficionados gather to trade observations, pontifications and gossip.

My cousin Don’s French friend Christian, a passionate follower of the bulls, had just arrived from Montpelier, France and he was just as eager as the rest of us to attend the bullfight that night. A fantastic lunch followed at the venerable Mauleon restaurant near the bullring, then Christian waded into the mob of ticket scalpers lining the Paseo Hemingway, soon emerging with tickets.

After a preparatory consultation with beer and Patxaran (Pacharán), a sloe-flavored liqueur of great renown, our group entered the bullring and found our seats. Much has been written about the Spanish cultural institution of the bullfight. Hemingway warned his readers to think of the bullfight not as a sport, but as a tragedy.

It is exactly as Papa said.

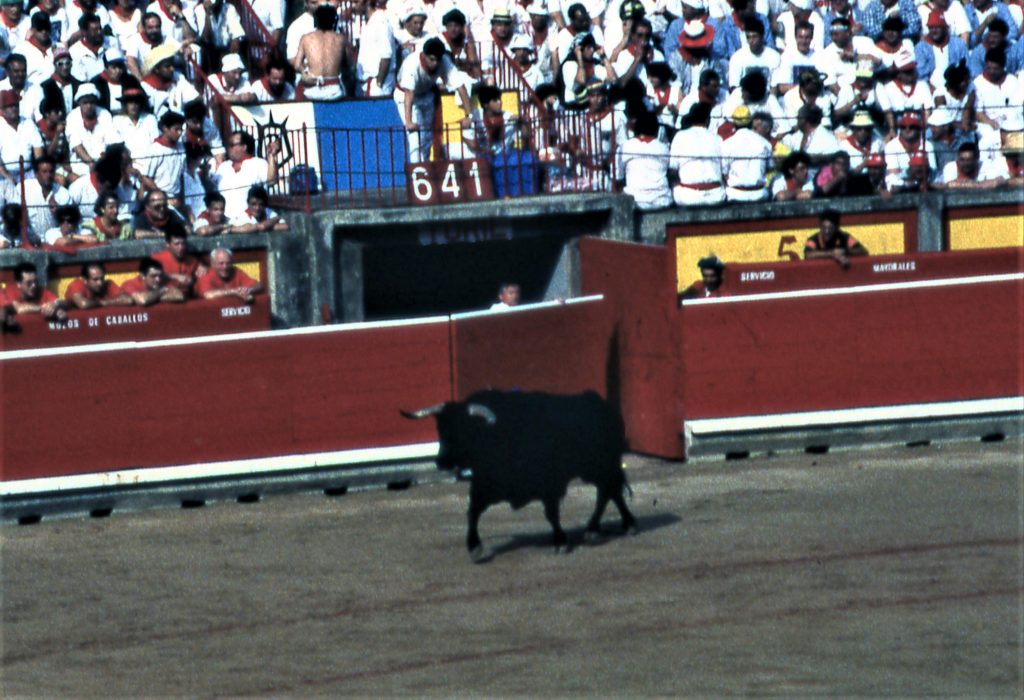

When the bull, which has been bred and raised for four or five years for no other purpose than to make his one appearance in the ring, enters the arena, he is doomed to die. The bull may take a human or two with him (less likely today than in the pre-penicillin era, when even a minor goring might lead to a severe infection), but he almost never lives. It cannot be said that the bullfight is a contest between equals. However, it is a fascinating event and one well worth attending.*

In the modern bullfight, six bulls are fought and killed by three matadors – one at a time, for a total of two bulls each. In Pamplona during the festival, this action has as its backdrop a rowdy crowd in the cheap seats (those not shaded from the late afternoon sun), most of whom are drinking from buckets of sangria or liter bottles of beer, typically spraying their drinks on those seated near to them.

Before the bullfight, these white-shirted spectators stagger through the streets toward the bullring, bearing their libations. After the bullfight, they stream out of the bullring toward the bars, most now bathed in damp hues of pink and red.

The death of the bull is strictly choreographed, and nothing preceding it happens without a reason.

At first, the bull is goaded into charging padded horses whose riders (picadors) use a long, bladed lance to work over the bull’s huge, humped neck muscle.

Next, men on foot (banderilleros) – virtual ballet dancers – plant short shafts with harpoon points into the same muscle. By weakening the bull’s upper neck to lower the animal’s head, these actions help to prepare the bull for the entrance of the matador, whose task it is to lead the bull through an artistic program of maneuvers with his capes and then to dispatch the tired, confused bull with the single thrust of a sword through the animal’s shoulder blades.

I am guilty of over-simplification in the preceding. As Hemingway wrote over a half-century ago:

“I went to Spain to see bullfights and to try to write about them for myself. I thought they would be simple and barbarous … but the bullfight was so far from simple and I liked it so much that it was much too complicated for my then equipment for writing to deal with and, aside from four very short sketches, I was not able to write anything about it for five years – and I wish I would have waited ten. However, if I had waited long enough I probably never would have written anything at all.”

A few brief paragraphs just can’t do justice to the diverse elements and strategies of the bullfight.

Here is one example. At the very beginning, when the bull charges into the ring, a committee of banderilleros with large capes awaits to lead the animal through brief maneuvers. Soon the men flee, and the bull emerges “triumphant” from this first encounter, the purpose of which is to permit the matador to observe the animal’s behavioral patterns; how it charges, which horn it favors, and so on. The subsequent efforts of the picador and banderilleros are meant to correct the tendencies thus observed and to regulate, insofar as possible, the bull’s physical bearing.

All these things occur without a scoreboard or a clock. The success of the matador and his associates is judged by the paid customers in the stands (fans, in American-speak), who applaud or jeer accordingly – and sometimes worse.

Hemingway explained his feelings about two detestable bullring servants in Death in the Afternoon:

“These two that I speak of are both fat, well-fed and arrogant. I once succeeded in landing a large, heavy one-peseta-fifty rented, leather cushion alongside the head of the younger one during a scene of riotous disapproval in a bull ring in the north of Spain and I am never in the ring without a bottle of Manzanilla (dry sherry wine) which I hope yet I will be able to land, empty, on one or the other at any time rioting becomes so general that a single bottle stroke may pass unperceived by the authorities.”

In conclusion, one of Hemingway’s most insightful and enduring reminders.

“After one comes, through contact with its administrators, no longer to cherish greatly the law as a remedy in abuses, then the bottle becomes a sovereign means of direct action. If you cannot throw it at least you can always drink out of it.”

The End: The Bull.

To kill properly, the matador must use his muleta (a special, smaller cape) to lower the bull’s head and expose the point of impact, then skillfully bury the sword in a small target area while avoiding the potentially fatal goring that might be inflicted by a horn should the bull raise his head at the wrong instant.

None of the six bulls I saw were killed cleanly; there were no perfect thrusts of the sword that drop him instantly.

In 1932, Hemingway was complaining about the lack of great killers among Spain’s matadors, and Michener echoed these thoughts in the 1960s, adding that in his many years of attending bullfights he had never witnessed one in which all aspects of the confrontation had been performed to perfection.

I did not come away from the bullring with any major misgivings as to the cruelty of the institution of bullfighting. The torture inflicted on the bull prior to his death is of brief duration, and certainly there would be more suffering if the animal were being prepared for veal production rather than public execution.

Those animals judged fit to be fighting bulls enjoy an extended lifespan as idyllic as any in the animal kingdom, and for those who are wondering, the characteristics of the fighting bull are transmitted through the animal’s mother, thus serving the purpose of a situation in which even the most successful products of breeding science must die at the peak of their performance.

Anyone critical of bullfighting who also eats meat might profit from speculating on methodology of the slaughterhouse before decrying the death of the fighting bull. At least vegetarian complaints are absent the tinge of hypocrisy.

The End: The San Fermin Experience.

After the bullfight ended, the sun was setting over the streets of Pamplona and the waning hours of San Fermin as we exited the bullring and walked along with the crowd toward the Mauleon, the aficionado’s restaurant and bar where we had eaten earlier.

Many people were chatting and drinking in the streets that cross in front of the entrance. I said goodbye to Don and his friends, downed a bit of the bubbly that poured freely, then returned to our room to pack and prepare for the early train to Madrid the following morning.

As it turns out, there is an end to San Fermin.

It comes when you’re leaning against your bag at the bar of the train station buffet, sipping coffee and watching an old man next to you swallow his morning brandy, and you realize that you’re still wearing the emblematic bright red scarf.

You think about removing it, and then remember what a good time it was, so you say the hell with it.

And you get on the train when it sidles up to the platform, and leave, though only temporarily, as ever thinking about the next time.

—

* More than two decades have elapsed since I last attended a bullfight. To be succinct, I no longer look at the institution in quite the same fashion as I did at the time I wrote this story. However, I’ve elected to retain the original wording; we can defer an examination of my evolving consciousness until later.