Fill with mingled cream and amber,

I will drain that glass again.

Such hilarious visions clamber

Through the chamber of my brain

Quaintest thoughts—queerest fancies

Come to life and fade away;

What care I how time advances?

I am drinking ale today.

—Edgar Allan Poe (1809 – 1849)

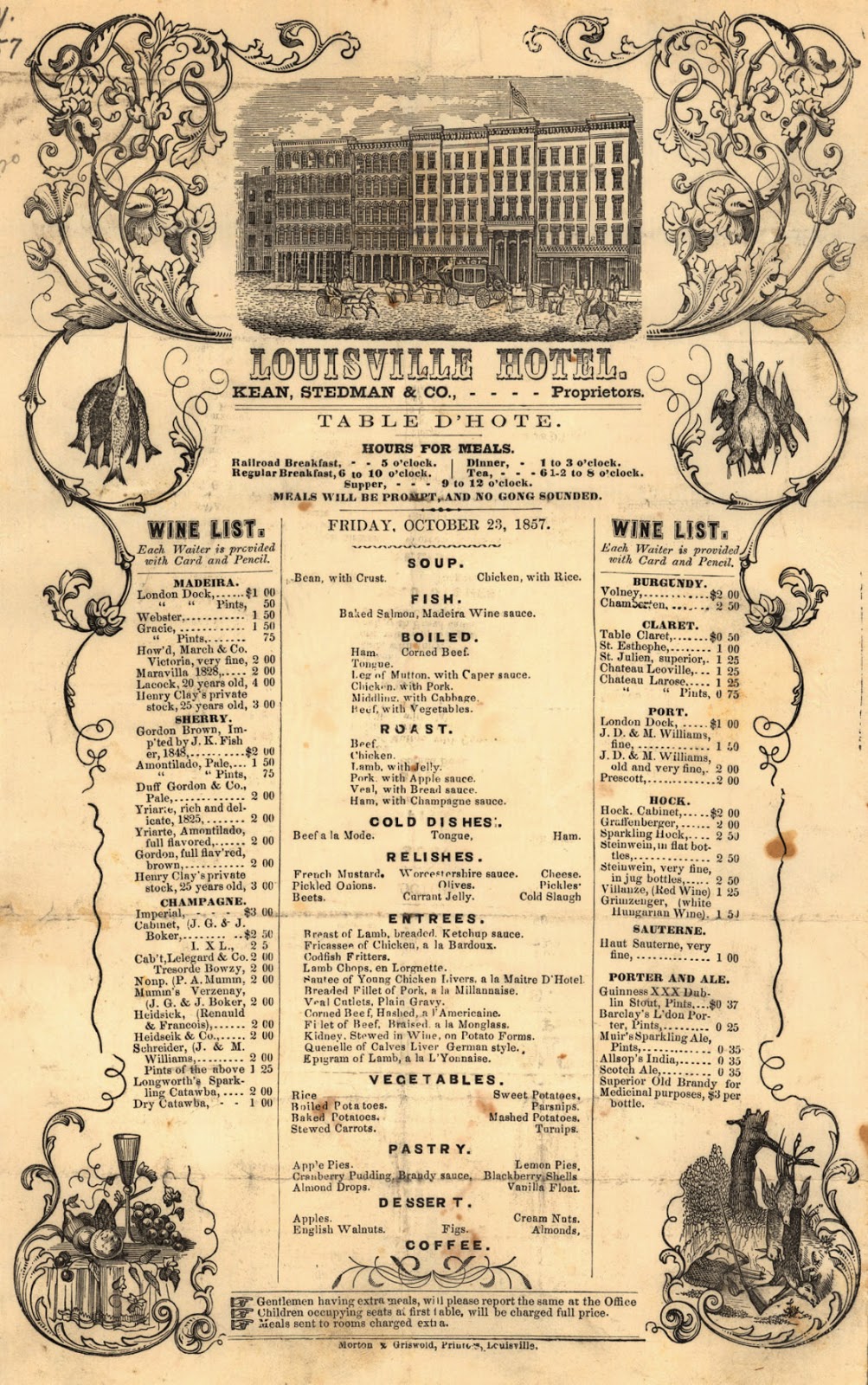

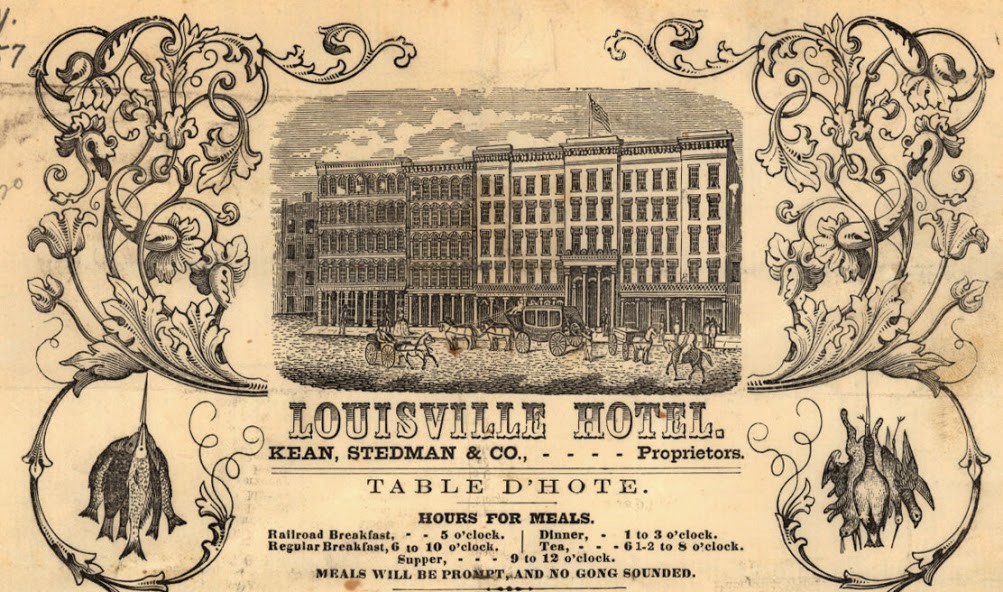

A long while back at the Louisville Restaurants Forum, the eternally helpful electronic institution created and curated by Robin Garr (the inimitable dean of Louisville food and drink writers), a user posted a photo of a Louisville hotel restaurant menu from 1857.

For once, we witness a literally antebellum phenomenon.

Recently I found the apparent source of this photo at Duke University, and what still strikes me about this menu—technically a broadside, defined as “a sheet of paper printed on one side only, forming one large page”—is the sheer novelty of viewing a pre-Civil War imported beer list offered by a top eatery right here in River City.

166 years later, such amenities cannot always be assumed.

I still recall an outing to a high dollar Louisville steakhouse on an evening long after better beer had become an established fact, where we observed numerous patrons quaffing Miller Lite alongside their $60 slabs of beef. It took my breath away; if you’re prepared to drop a couple hundred on a meal, wouldn’t you drink decent wine?

If not, maybe a nice Chimay as substitute for the vino?

When I asked for the steak house’s beer list, a familiar litany was recited by the server: “We have all the beers: Bud, Bud Light, Silver Bullet,” etcetera, etcetera (and assuredly ad nauseam).

But imagine debarking from the steamboat in Louisville during the Buchanan administration, stowing your trunks in the Daniel Boone Suite at Louisville Hotel, and bounding downstairs to the restaurant to choose one (or maybe all) from this list of five highly rated imports, each of them differing from the other stylistically, and not a single low-calorie abomination to be found.

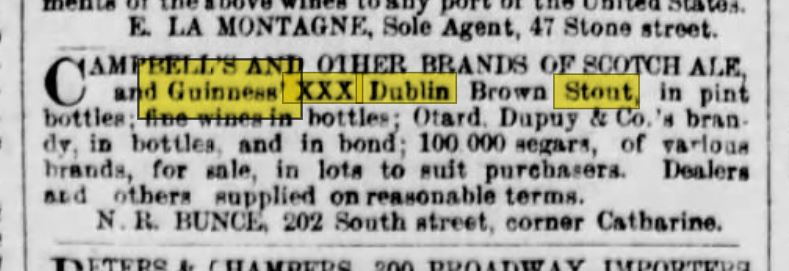

Guinness XXX Dublin Stout $0.37

Guinness XXX Dublin Stout $0.37

In 1857 the world famous St. James Gate Brewery in Dublin was a mere two years away from celebrating its centennial, and was vastly experienced as an exporter.

It seems reasonable to assume that Guinness XXX Dublin Stout was not a lower-gravity, present use ale, but equivalent to the formulation we know today as Foreign Extra Stout, with a higher alcohol content and added hopping rates to withstand the rigors of shipping.

Barclay’s L’don Porter $0.25

Barclay, Perkins & Company was a monolithic presence in London from its founding in 1771 and well into the 20th century. Porter was the brewery’s meal ticket at first, and although the style fell from fashion by the mid-1800s, the export trade apparently remained robust in 1857.

British beer researcher Ron Pattinson explains that at this precise period, Barclay Perkins was shipping a Porter to India that ironically bore many of the hopping characteristics we’d now identify in a Black IPA. Might it have been this at Louisville Hotel?

EI stands for Export India. This is the Porter that Barclay Perkins produced for the Indian market. It’s the Porter equivalent of IPA. As I keep reminding anyone who will listen, there was probably more Porter exported to India than Pale Ale. But for some reason that seems to have been forgotten, with everyone focusing completely on IPA. It’s most likely a class thing, IPA having been drunk by officers and officials, Porter by the ordinary soldiers.

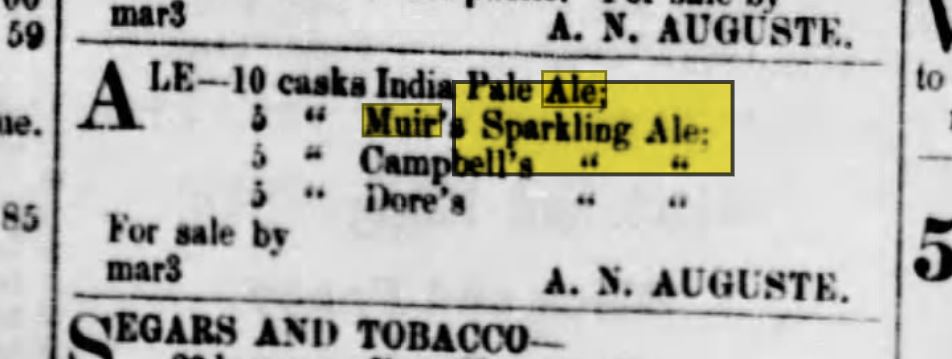

Muir’s Sparkling Ale $0.35

It isn’t difficult to find references to John Muir’s 19th century Calton Hill Brewery in Edinburgh, but unraveling the composition of “Sparkling Ale” takes some digging, hence Randy Mosher’s seminal Radical Brewing: Recipes, Tales and World-Altering Meditations in a Glass, published in 2004:

“Sparkling ale is a trade term for a bottled beer that seems to have originated in Scotland as a somewhat lighter, more drinkable product than many of the brutally strong ales of the day.”

I suppose “drinkable” is a relative term, as the revivalist homebrew recipe Mosher offers up (admittedly with a high degree of guesswork on the author’s part) posits an ABV of 5.8% – 6.4%. However, this strength would assist in stability for travel. Interestingly, the old records and logs Mosher uses reveal a lactic acid presence in keeping with wood aging and Brettanomyces activity.

The “sparkling” designation is applied only to bottled beers and seems to have indicated a highly carbonated product. The Scots were pioneers in the bottle manufacturing business, and by 1850 were turning out well-made stoneware bottles capable of fairly high pressure.

And:

Sparkling Ale was being bottled and sold by Younger and McEwan and others by at least 1885, and was exported in large quantities to America and the Empire. Homegrown versions turned up around that time in the United States and in Australia, where the beer still survives at Cooper’s and a couple of breweries in Adelaide. But, alas, no longer in Scotland.

Mosher mentions that in the 19th century, Scottish beers across the board had a reputation for fuller flavor, achieved in part by fermentation temperatures lower than their English brethren.

This observation fits hand in glove with the key date of 1835, when Muir became the first brewer of lager in Scotland, using a Munich yeast sent to him by the pioneering lager brewer Gabriel Sedlmayer of the Spaten brewery. The experiment was short-lived, but according to Martyn Cornell:

Scottish landlords seemed to love the beer made with the Munich yeast, but Muir couldn’t keep the strain pure and stopped using it. It is one of brewing history’s more titillating “what ifs” – what if Muir HAD been able to keep brewing with Munich yeast, the way Jacobsen did at Carlsberg and Heineken did in the Netherlands?

Allsop’s India $0.35

Allsop’s India $0.35

By 1809, Hodgson’s Brewery had parlayed its location near London’s East India docks into a commanding commercial presence in India, specializing in shipping its hopped-up Pale Ale to the British colony (a trade that predated Hodgson’s to 1717 or even earlier).

However, the East India Company eventually sought to dilute Hodgson’s near monopoly, and a company director commissioned Samuel Allsopp & Sons in Burton-on-Trent to come up with its own formulation. The sulfate-rich water in Burton proved superior for brewing strong, hoppy ales.

Allsopp took a bottle of Hodgson’s India beer back to Burton and handed it to his head brewer, Job Goodhead. Goodhead spat the beer out, offended by its bitterness, but said he could replicate it. According to a local legend, Goodhead made a small sample of beer using a tea pot as his mashing vessel, with only pale malt. The experiment was triumphant and Allsopp started to export pale ale with such success that in 1859 he built a new brewery in Burton opposite the railway station.

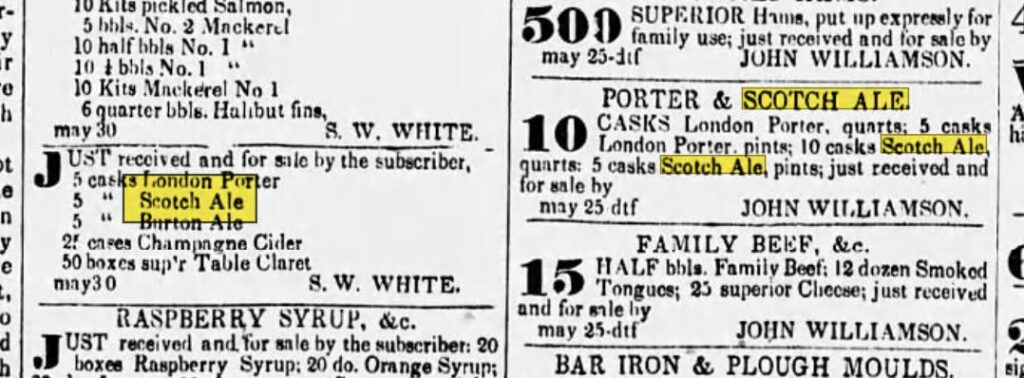

Scotch Ale $0.35

Scotch Ale $0.35

The only beer on Louisville Hotel’s 1857 imported beer list without a brand name attached is Scotch Ale. Might it have come from Muir, Younger, McEwan or Campbell?

In modern times, we’d infer such an ale to be a rich, amber-dark Wee Heavy, circa 6.5% – 10% ABV: “Rich, sweet malt depth with caramel, toffee, and fruity flavors. Full-bodied and chewy, with warming alcohol. Restrained bitterness, but not cloying or syrupy.”

Amid this speculation, we know for certain that in 1857 the transplanted Scotsman Hew Ainslie, who founded breweries in Shippingport (1829) and New Albany (1840), was living and working in Louisville.

Homebrewer and beer researcher Conrad Selle, co-author (with Peter Guetig) of Louisville Breweries: A History of the Brewing Industry in Louisville; Kentucky; New Albany and Jeffersonville (1995), probably is the foremost local authority on Ainslie’s amazing life.

Many early brewers worked their trade as a sideline or temporary trade before moving on to other occupations. Hew Ainslie is unique for having been principally a poet.

We can surmise that had Ainslie sampled the beers at Louisville Hotel, he’d have been a trustworthy judge of their quality.

There is no specific information to be found as to the products of the breweries with which Hew Ainslie was involved in Louisville and New Albany, but we can surmise from the available evidence that they were typical small breweries of the time, with four or five employees, making ale, porter and stout. As a man who appreciated truth and beauty, it is likely that Hew Ainslie made good malt, and being conscientious with it, good beer as well.

—

When it comes to analyzing all of this information, a few noteworthy themes emerge.

Prominently, Louisville Hotel’s beer list is a snapshot of an era about to be turned on its head—not only by the Civil War, but owing to the arrival and prospective supremacy of German-influenced lager brewing. After the Civil War, the focus changes to domestically-brewed, German-heritage lagers.

Accordingly, the hotel’s beverage selection attests to the maritime might of Great Britain and the original value of America’s waterways as the interstate highways of their time. New Orleans was the South’s largest city and busiest port, and both the Mississippi and Ohio could be navigated all the way to Louisvile’s falls (hence Portland’s reason for existence).

It remains unclear to me whether the Louisville Hotel’s imported beers were shipped in bottles, or casks, or a combination, as with the three identified in the broadside as being served by the pint. Old newspaper ads specify both casks and bottles being shipped. I’m also aware of the tradition of 19th century breweries contracting with local bottling firms to fill what were, in effect, rental bottles (as with the Renn bottler in New Albany).

Furthermore, quite apart from beer, we’re viewing a wine list alone, albeit it one that included more potent fortified examples of Port, Madeira and Sherry (and if you’re wondering what “Hock” is, it’s a British term for German white wine).

In short, bourbon is quite obviously missing, although strangely appended to the imported beer list is brandy (for medicinal purposes) at a whopping $3 per bottle. I don’t know the reason for this omission; perhaps the tourist authorities of 1857 hadn’t yet grasped the utility of Greg Fischer’s “bourbonism.”

The answer might be discerned between the lines here:

Relative to modern legal standards, it’s common to assume that alcohol restrictions were lax in the 1860s—if not altogether nonexistent. In fact, before proceeding with our story, it’s worth taking a moment to note that the production, sale, and consumption of distilled spirits in Kentucky were heavily regulated in the 1860s, almost as much as they are today.

Maybe the Louisville Hotel had a bar separate from its dining room. Or, management recognized that in a city awash in whiskey and locally-brewed beer, cultivating a loftier appearance was beneficial to its lofty brand. After all, numerous taverns were nearby, and we can surmise the desk clerks being of assistance to residents in need of a belt.

As for what these antebellum imported beers cost relative to today, here is no simple way to accurately quantify the prices charged in the sense of valuing yesterday’s dollar versus ours. Doing so implies a breadth of knowledge beyond my current objective, including familiarity with prevailing wages, costs of living in other areas, and other factors.

This said, $1 in 1857 is equivalent in purchasing power to about $34.58 today. A 35-cent beer then is equivalent to $12.00, or some such. Do I have this backwards? In any event, with a skilled worker in 1857 earning $600 – $800 per year, these were pricey beers.

As were the meals. You’ll note there are no food prices on the broadside, presumably because they were included with a room with board arrangement (“meals will be prompt, with no gong sounded”), with the alcoholic drinks available a la carte.

Glancing elsewhere for parallels, it seems the foodstuffs at Louisville Hotel might total as much as $10 per day per customer (I’m open to correction, by the way), which suggests that only high rollers need have applied for rooms there.

Alas, Edgar Allan Poe, who was quoted at the beginning of today’s journey to the past, leaves no record of visiting Louisville, although the British superstar writer Charles Dickens did, spending an evening at the original Galt House in 1842.

“The road was perfectly alive with pigs of all ages, lying about in every direction, fast asleep or grunting along in quest of hidden dainties.”

Fifteen years later, Louisville Hotel’s kitchen could render these hogs into “Breaded Fillet of Pork a la Millannaise.” Roasted pork with apple sauce was on call, along with ham, boiled or cold. I’d probably accompany an order of each with a Barclay’s London Porter, saving the Guinness for tomorrow’s Codfish Fritters.

By any reckoning, it’s an incredible “wayback machine” thought experiment.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 41 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 41 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.