I haven’t visited Denmark’s wonderful capital city of Copenhagen often enough in recent years. This negligence is being rectified as you read. Copenhagen (population 775,000) has remained a great favorite since my first trip abroad 38 years ago, prompting me to offer a few reasons why I like it so much.

First and foremost, as counted among Europe’s northern “Nordic” countries, Denmark is a progressively governed land where social services have continued to be maintained for the benefit of all citizens—imperfectly, I imagine, but at a far more impressive level of achievement than my own country’s “trickle down” mentality has managed to underachieve during my lifetime.

Besides…

- Very dear friends live in Copenhagen.

- The city is simultaneously venerable and ultra modern.

- Bicycles are everywhere with world-class infrastructure to match.

- An efficient (nay, relentless) public transit network takes you just about anywhere for a reasonable price.

- The food and drink suits me, from open-face sandwiches to herring to hot dogs to akvavit, AND I’ve always been partial to the classic Danish lagers of the pre-“craft” period.

Exploring Copenhagen as a rookie budget traveler in 1985, I found the Carlsberg and Tuborg breweries ubiquitous—and if a duopoly is inevitable, it’s better to enjoy everyday brands for mass consumption (Hof and Grøn, respectively) that tasted far better to me than the American mass-market brands flooding a supine market back home.

I’m hoping they still do.

As it turned out, Carlsberg served as the venue for my first-ever Old World brewery tour (Guinness in Dublin preceded Copenhagen, but consisted only of a brief film and free pint). According to my records, the Carlsberg tour capped off a frenetic Monday in 1985, exhausting me from the mere recollection.

Then again, I wasn’t quite 25 years old back then, and apparently had energy to burn.

In those early days my lodgings of choice were inexpensive youth-oriented hostels, some official and year-round, others seasonal and temporary; the latter generally were located in university dorms, and their availability logically coincided with academic breaks.

However other creative ways could be found to house youthful (and young-at-heart) peak season tourists existing on the cheap, hence an ice skating rink in Copenhagen that bore the name Sleep In. Of course, the ice had melted, and the expanse of the floor was divided into multi-person pods with bunk beds.

On the Monday morning in question, I departed my skating rink bunkhouse early in the morning and took a bus to the central train station, checking my bag at left luggage, and securing an overnight couchette (i.e., a seat that could be converted into a sleeping berth) reservation for Oslo, Norway. The train would be departing around 21.00 … or 9:00 p.m.

(The 24 hour clock had started to make sense, along with beer glass measurements, although thermometers remain slightly mysterious these many years later.)

Twelve whole hours of frenetic activity lay ahead, and fortunately my Eurail Pass covered the regional “S” commuter network. Consequently, a pleasant sunny morning was spent in the nearby city of Hillerød, traipsing the grounds of the Frederiksborg Castle. On the way back came a stop at Copenhagen’s Churchillparken, site of an old star-shaped earthen military redoubt and the Museum of Danish Resistance (to the Nazi occupation in WWII).

By mid-afternoon, I’d finally gravitated back to the Vesterbro neighborhood, stepping off the “S” near the Carlsberg brewery’s 19th-century rail yard complex in Valby. The proximity of trains provided a valuable lesson for future European beer hunting expeditions, because breweries of a certain pre-automotive period almost always are located near railroad tracks or navigable waterways – the interstates of their age.

At the time of my visit, formerly independent Tuborg still brewed beer at its own historic plant north of center on the other side of town, having merged with Carlsberg decades before but maintained its separate identity. Tuborg, which I finally toured in 1993 prior to its closure, had its very own shipping docks amid an industrial area long since redeveloped into mixed-use neighborhoods.

In 2023, Carlsberg remains an iconic international beer brand, recognizable the world over for the green label and unique script of its flagship, Carlsberg Hof, a mild Pilsner-style golden lager. Significantly, the beer wasn’t always golden. Nor was it always a lager. Carlsberg’s first batches in 1847 were dark-colored ales.

Founder J. C. Jacobsen was the son of a brewer, and his career began at a propitious time. Numerous factors were converging during the mid-1800s to make possible the seismic transformation of the beer business from a typically localized and smaller-scale supplier of old-school ales to the eventual global reach of mass-produced golden lagers, as brewed at huge factories just like Carlsberg’s.

Jacobsen had no specialized academic background, but he was astute and industrious. His European contemporaries Gabriel Sedlmayer and Anton Dreher were acclaimed pioneers of lager brewing, and because they didn’t think in proprietary terms, the Dane freely borrowed from their expertise, making frequent journeys south for continuing education.

Jacobsen had no specialized academic background, but he was astute and industrious. His European contemporaries Gabriel Sedlmayer and Anton Dreher were acclaimed pioneers of lager brewing, and because they didn’t think in proprietary terms, the Dane freely borrowed from their expertise, making frequent journeys south for continuing education.

It is said that Jacobsen transported fragile lager yeast from Munich to Copenhagen, keeping it cool in his stovepipe hat. More importantly, he funded a laboratory and commenced a rigorously scientific approach to brewing, correctly foreseeing the value of a consistent, replicable product in the context of an emerging global economy.

However, neither Jacobsen nor his son and eventual successor Carl were robber baron capitalists. To them, brewing was more about technology than art, but the profits were a different story. Father, son and Carlsberg became models of 19th-century industrialized philanthropy, with the family’s brewing interests bequeathed to a foundation with numerous scientific, cultural and artistic non-profit imperatives. (* see note below)

In the temporal sense, much about Carlsberg has changed since my first glimpse of Copenhagen in 1985. The company has made dozens of global acquisitions, and there was a structural reformatting after the fall of Communism.

Brewing effectively moved to a different location in Jutland in 2008, and the “old” brewery in Copenhagen survives as a company headquarters, tourist destination, and historic site, producing specialty “craft” brews; the visitor center has been closed for remodeling since the pandemic and is reputed to be reopening this autumn. Just as with Tuborg, the former acreage of the industrial plant in Valby is being redeveloped as a whole new city quarter.

However, Carlsberg still fulfills its philanthropic mandates as a foundation, and I’ll always feel better drinking a multinational Carlsberg than a beer brewed by the likes of AB-InBev.

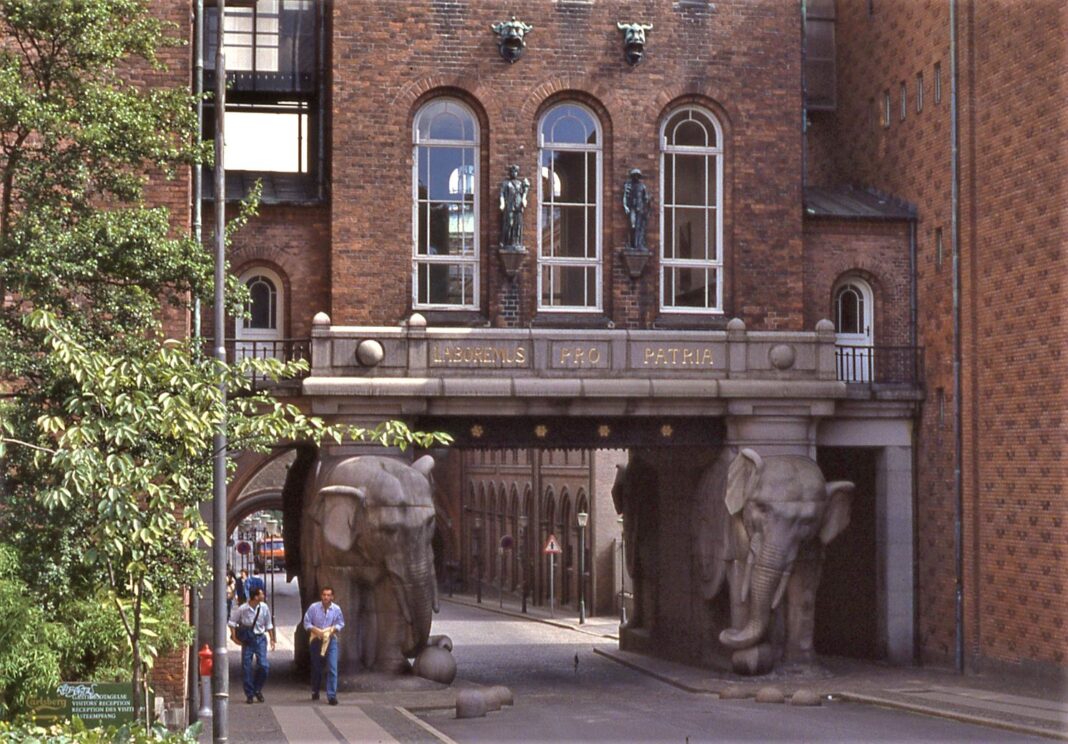

“Old” Carlsberg’s most enduring architectural feature is the imposing stone Elephant Gate standing just outside the 19th-century brew house. Generations of multi-lingual brewery tour guides began here, having been drilled to immediately disavow the presence of swastikas carved into the elephants’ pedestals, paraphrasing:

“These are ancient symbols of auspiciousness, luck and well-being. The word ‘swastika’ itself is Sanskrit, not German, and these have nothing to do with that other fellow during the last war.”

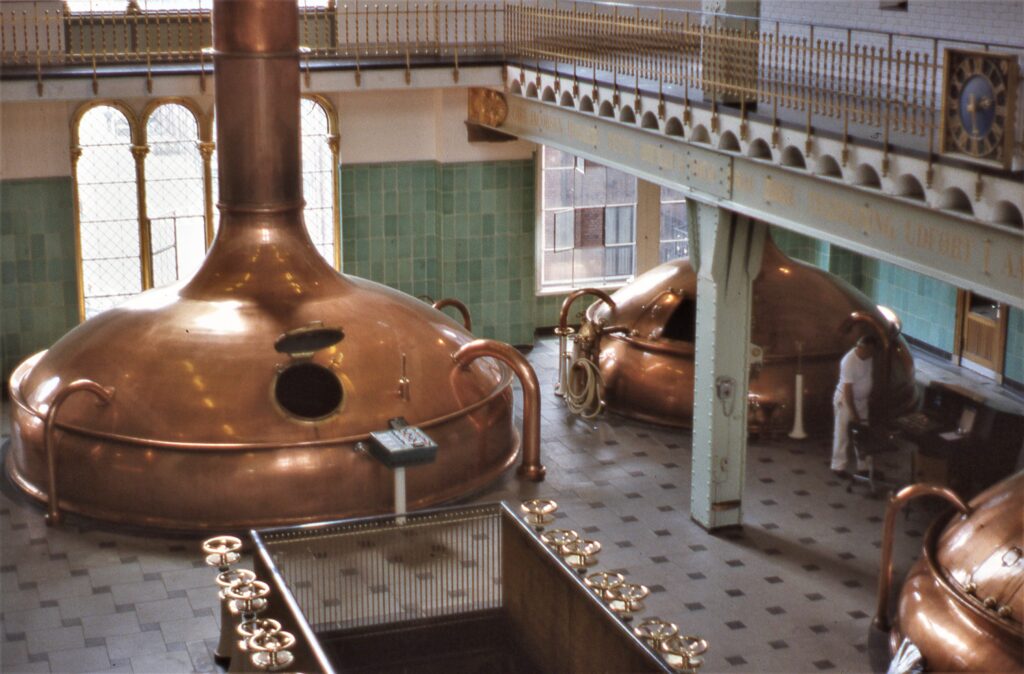

Point taken, and yet returning to that day in 1985, those unfortunate swastikas were dwarfed by the artistry of the stone pachyderms, then hushed, cathedral-like echoes amid magisterial coppers.

The guide spoke about barley malted and mashed, sugar water created, hops added during the boil, and yeast merrily eating sugar to create alcohol and carbonation. The conclusion came via a mezzanine view of Carlsberg’s throbbing, cacophonous bottling line.

It stands to reason that a brewery like Carlsberg cunningly placed these tours in a compelling architectural and historic context. If 19th-century industrial buildings like these did not continue to fascinate modern man, we wouldn’t rush to convert them into condos, and if advertising graphics from olden times ever cease to encourage feelings of loyalty and cultural identification, we’ll have no breweriana collectors.

Unfortunately, the litigiousness of our modern world has gone far toward spoiling the ultimate objective of brewery tours, because who would endure the beer factory stroll without a prospect of tasting the bounty?

Because: I heard and later repeated the brewery tour gospel hundreds of times, and the process nearly always made me thirsty.

Ready for a closing nip, visitors? Well, come right this way.

At the end of my first Carlsberg tour, the participants were seated at tables in a room festooned with brewery agitprop. Sample beers in lightly chilled bottles already were lined up and ready on each table, with a few salty snacks and gratis souvenirs—stickers and decals, maybe some paper labels. There was joy and delight all around.

It seemed odd to me at the time that families with young children would be taking the Carlsberg tour, but upon reflection it made sense. This was free-wheeling Europe, not puritanical America. There were soft drinks for the kids, and only later did I do the requisite math and realize that the solo traveler’s best strategy at such times was to stick close to the families, be smilingly gracious, and when invited to occupy the single spare seat at a table set for six, join them.

Only the adults were drinking the beer, and obviously, this meant more for me.

Skål!

* NOTE: About the Carlsberg Foundation

The Carlsberg Foundation was established in 1876 to support science.

In 1882, J.C. Jacobsen bequeathed all of his property, including his brewery, to the Carlsberg Foundation. Following the Brewer’s death in 1887, the foundation took over the brewery on October 1, 1888. Since then, the Carlsberg Foundation has overseen the Carlsberg Group, ensuring that the brewery is run with the focus on innovation and high-quality products. In accordance with the Brewer’s wishes and vision the Carlsberg Foundation gives back the dividends from the shares in Carlsberg A/S to society by supporting excellent basic research within the fields of natural science, social science, and the humanities.

The Foundation’s further obligations include supporting the research at Carlsberg Laboratory, maintaining and developing the Museum of National History at Frederiksborg Castle and granting funds for socially beneficial purposes through the Tuborg Foundation, especially in support of youth communities.

The Carlsberg Group is currently the only global brewery owned by an enterprise foundation.

For further reading:

40 Years in Beer, Part Fifteen: A clash of titans (with Elephant Beer) in Copenhagen, 1987

40 Years in Beer, Part Twenty-Two: A placid traditional Danish lunch in Copenhagen, 1989

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 41 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 41 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.