“The secret of a happy life is to know when to stop—and then go that bit further.”

—Inspector Morse, classic British television police crime solver

The very least I could do during two weeks spent in England’s lovely West Country was to ingest my gout medicine each and every morning without fail—preferably washed down with a pint of cask-conditioned Bitter from one of those pubs nearby, already dispensing it, but in a pinch, grudgingly conceding the utility of mere tap water.

Yes, I know: Fish do IT in THAT.

The solution? Eat more fish, especially with chips.

Somewhere a health fanatic reads and brays with dismay, but have no fear. It’s only despairing, defeatist clatter of the sort Winston Churchill wouldn’t have countenanced, even after his morning bottle of champagne, and these naysayers are inaudible to me, fully muffled by the cacophonous sizzle of a traditional English breakfast frying atop the stove, even that waxy tomato from Tesco’s, because it is destined for maximum exposure to hot oil just like all the rest.

Somewhere a health fanatic reads and brays with dismay, but have no fear. It’s only despairing, defeatist clatter of the sort Winston Churchill wouldn’t have countenanced, even after his morning bottle of champagne, and these naysayers are inaudible to me, fully muffled by the cacophonous sizzle of a traditional English breakfast frying atop the stove, even that waxy tomato from Tesco’s, because it is destined for maximum exposure to hot oil just like all the rest.

Queue the Elgar, and consider this partial list of foodstuffs joyfully consumed during my holiday, including both local “English” fare and widely available culinary options borrowed from elsewhere.

Anchovies fillets (fresh)

Bacon

Baked beans

Bangers and mash

Black pudding (i.e., blood sausage)

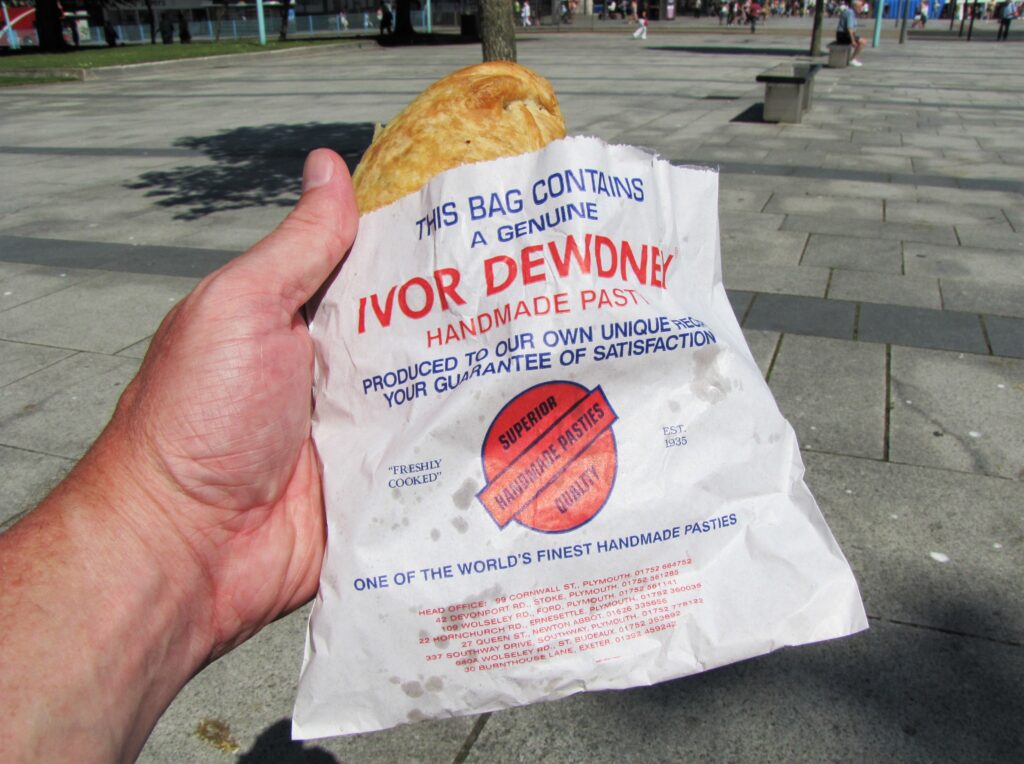

Cornish pasties

Crab sandwiches

Egg rolls

Falafel

Fish pie (not Stargazy pie, alas)

Gajrati (regional vegetarian Indian)

Haddock and chips

Pie, mash, eel and liquor (the latter is gravy)

Pizza (loaded)

Smoked salmon

Spanish tapas

Steak & kidney pie

Thai red curry

Yorkshire pudding

Alas, I digress.

It generally is my custom to entertain and inform in purely fermentable measures of prose, and yet on this English holiday in July, 2013, I found it quite unthinkable to separate the culinary from the ale-mentary.

Overall, ways of the new were not my objective, and I did not search for top chefs flashing their own branded aprons and sauces. Rather, my task was to focus on the glories of the much maligned traditional English table, and to accompany them with the native genius for classic ale-making.

Mission accomplished.

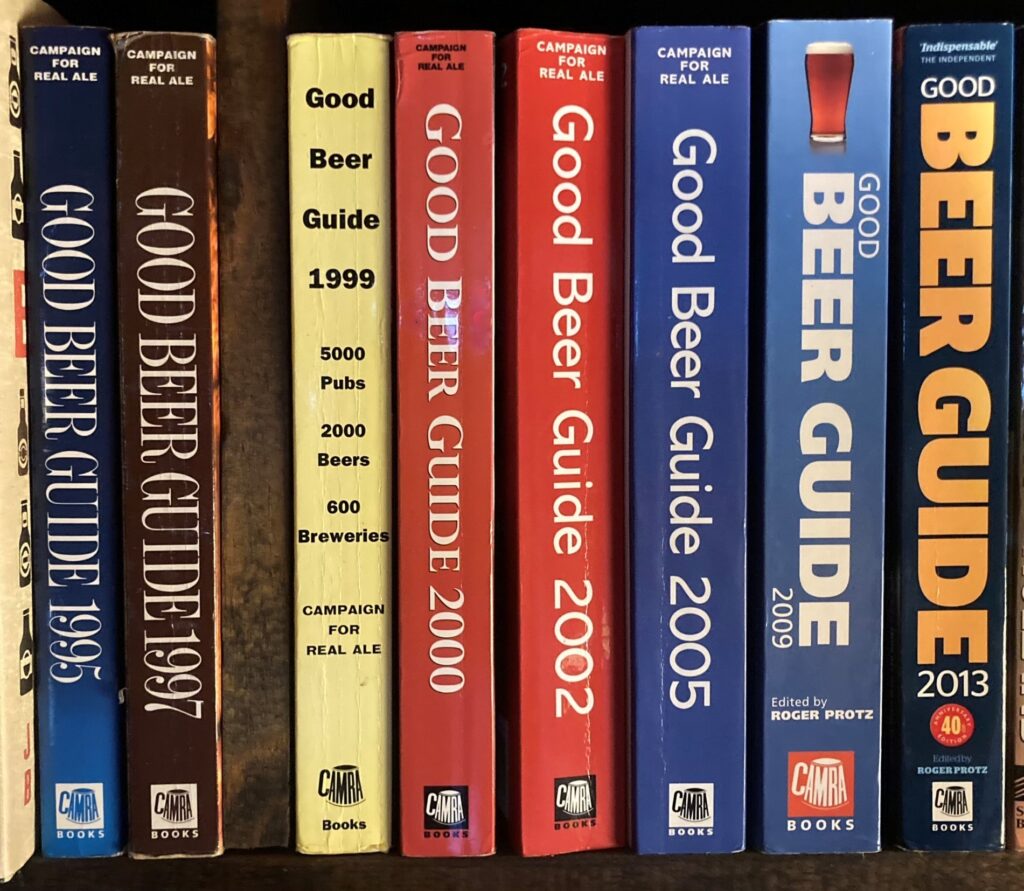

First, let’s review the liquidity to be found in a reference volume.

Just after purchasing plane tickets, and before any other arrangements had been made, I purchased the essential book for ale hunting in the United Kingdom: “Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) Good Beer Guide,” edited by Roger Protz, and fully revised for publication each year (and yes, there now is an app).

CAMRA is the beer world’s oldest and most doggedly pervasive consumer protection society, founded in 1973 for the express purposes of espousing and protecting cask-conditioned “real” ale from the intrusions of modern times. What exactly is cask-conditioned “real” ale? CAMRA explains:

Real ale is a natural product brewed using traditional ingredients and left to mature in the cask (container) from which it is served in the pub through a process called secondary fermentation. It is this process which makes real ale unique amongst beers and develops the wonderful tastes and aromas which processed beers can never provide.

Just know that traditional cask-conditioned ale is a living entity. It is pre-industrial, “slow” beer at its finest, predating every advance in ease of packaging, and preceding all processing shortcuts undertaken for the sake of modernity.

Consequently, as a product requiring training, thought and effort to maintain and dispense properly, real ale and the pub where it is consumed are inextricably linked. In America, the “coldest beer in town” meekly signposts a mere triumph of refrigeration. In England, the best pint of real ale within walking distance of a bus stop is stirring testament to the publican’s commitment to craft.

That’s why CAMRA’S beer guide is vital. The organization’s local chapter members serve as diligent boots on the ground, studiously analyzing ales and pubs on a daily basis. Their intelligence gathering is the heart of the book, making it the top source of information for the visitor who cares less about his bed and breakfast than finding pints of fresh ale.

Which pubs are tops at tending their firkins? What do they usually pour? Do they serve snacks or meals? Are they hosts for discourse in their community? The book provides these answers, and many more.

My first visit to Devon and Cornwall was in 2009, and four years later, there were many changes in the pub scene. Owing to regulatory, political and societal factors too numerous to recount, pubs in the UK are diminishing in number, and that’s a bad sign. At the same time, there are more breweries now at work than at any point in a half-century.

Dozens of newcomers are brewing classic ale styles—Mild, Bitter, IPA, Stout and Porter—alongside newer variations, and they’re supplying local pubs. There may be fewer venues, but the range of choice probably is greater. Session strengths (below 4.5% abv) remain the norm, and while I might drop names (St. Austell, Skinner’s, Summerskill and Bridgetown), it wouldn’t matter, because none of the beers brewed by these excellent breweries are available anywhere close to Louisville.

This is as it should be. They await your arrival, over there.

On a sunny Sunday in July, my wife’s cousin drove us from the city of Plymouth to the Dartmoor National Park. There, surrounded by rolling, sparse uplands and freely roaming sheep, we dined at a venerable establishment called the Dartmoor Inn in Merrivale. I enjoyed roast beef with gravy, cabbage, vegetables and Yorkshire pudding. Two pints of well-tuned local Jail Ale from the Dartmoor Brewery in nearby Princetown completed this time-honored Sunday Roast.

Frankly, I gloried in the ambience: Dark walls, wooden beams, a low-hanging ceiling and a fireplace, with humps, stoops and irregular measurements, and overall, minimal space for a heavyweight like me to navigate. The roasted meal was deliciously overcooked, and the ale’s ideally balanced malt and hops kept my palate sharp amid the meat and butter. It was the embodiment of a lifetime’s fascination with BBC News, “The Last of the Summer Wine” and maritime gin rations.

But what of the calories and cholesterol?

Whenever healthful thoughts began encroaching, I merely reached for another custard tart, found the closest CAMRA-listed pub, and waited for the feeling to pass.

Brew, Britannia.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 41 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 41 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.