When I was a boy, and my mother wasn’t looking, my father would give me sips of his favorite beer, which was a Hazy IPA brewed with experimental hops from New Zealand.

It was okay, but I liked it better when his buddies came over to shoot the breeze. Everyone brought a different brew, and this is how, by the age of 12, I could tell a rustic Belgian-style farmhouse Saison ale crafted in Italy from a barrel-aged Imperial Stout originating in a brewery occupying the footprint of an abandoned Soviet toothbrush factory in Romania.

And speaking of teeth, I’m lying right through mine.

It’s not inconceivable that a thirty-year old today, in 2021, could be truthful if spinning the preceding yearn, but your humble correspondent is too old to get away with it, having embarked upon his seventh decade.

But those wee training-wheel nips during the late 1960s were very real. It’s just that they did not include ales, much less “craft” beers or imports.

All those far-off samples were lagers from Falls City, Falstaff, Wiedemann or Sterling, regional remnants of then-besieged American traditions in beer, which since the mid-1800s had been adaptive exemplars of a Central European way of thinking, brewing and drinking.

We’ve long since chosen to refer to these collectively as “German” ways, and while not entirely accurate, it’s close enough for krausening. Let’s pause for background.

Taxonomy is the classification of something, and in the case of beer, it’s basically a three-way division: lagers, ales and wild fermentation.

The differences have nothing to do with color or alcoholic strength, but with yeast and the method of fermentation. Lagers have cooler fermentation temperatures and a period of cold aging; ales result from warmer fermentation temperatures and customarily can be consumed more quickly; and “wild” means a beer is fermented as a whole or in part with the assistance of yeast, bacteria or microflora apart from traditional brewer’s yeast.

Characteristic flavors and aromas derive from these techniques, but let’s not dive down that particular rabbit hole just yet.

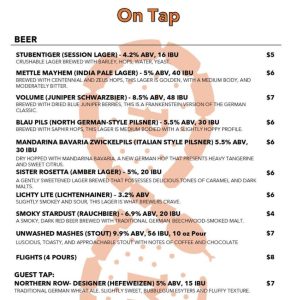

Recently I stopped by Dragon King Daughter’s location in New Albany and saw an entirely unfamiliar beer and brewery on the menu: Rebel Mettle’s Stubentiger, clocking in at a poundable 4.2% abv, and described appropriately as a “session lager.” It struck me as a mild variant of Helles, which in the German dialect of beer-speak is the word for pale and golden.

In fact this year-old Cincinnati brewery actually specializes in lagers, as opposed to Belgian ales or terroir-generated tastes of the wild. A quick glance at Rebel Mettle’s taproom beer list has me both salivating and considering a road trip up I-71 to the Queen City.

In fact this year-old Cincinnati brewery actually specializes in lagers, as opposed to Belgian ales or terroir-generated tastes of the wild. A quick glance at Rebel Mettle’s taproom beer list has me both salivating and considering a road trip up I-71 to the Queen City.

To be sure, new-generation American breweries elsewhere in our region, like Urban Chestnut in St. Louis and Chicago’s Metropolitan, have been going deep into the lager-derived style inventory for a while, and Louisville’s branch of Gordon Biersch began as a lager house of sorts, although brewhouse autonomy has broadened the palette in recent years.

Many, maybe even most, local breweries brew a lager beer or three, and some of them are quite good at it, but none have chosen to make lagers their broad specialty. It might be noted that German ales matter, too: Kölsch, Altbier, Hefeweizen, Berliner Weisse and Gose, the latter pair especially prone to reinterpretation by American brewers.

However, for now I’m keeping to the cool fermentation side of the ledger. Early this year, Beverage “Follow the Money” Dynamics made this observation in its annual “trends to watch” column (bold font is mine).

While German lagers or Belgian tripels may never rule the category, the quality of European-style beers made in America has never been higher. And more consumers have caught on. Partly this is newer craft drinkers progressing from approachable hazies to other beers. Then there’s the old-school crowd that never stopped loving lagers and European recipes. While this trend will unlikely blow up in 2021, it should remain a relevant (and profitable) niche.

Today’s ruminations are not intended to embrace a detailed examination of lager in the context of American non-mass-market brewing, although there are simple explanations for why it has taken three decades or more to circle back to a place that was the starting line for so many of us.

Most obviously, the planetary ale lexicon was woefully under-represented in the dawning age of American micro-craft brewing. The German heritage in American brewing had been corrupted, and the playing field cleared for the beer equivalent of Bunny Bread. Ale was the best radical corrective to the Empire of Wet Air, and so we began with a a panoply powered by warm fermentation.

Ale can be conceived, brewed and served in a far shorter period of time than lager, and this has always been a prime consideration of brewhouse economics.

Mash tuns, brew kettles and fermenters are machines in a factory, whether great or small, and typically they are financed to work at maximum capacity. Lagering time is an investment in itself. If not factored into the business plan, lagers can be a challenge to work flow, dollars and sense; not only that, but they demand a level of skill to be rendered properly.

For me, as one presently employed in reselling better beer and not creating it from scratch, lager styles are the newfangled wave of old-school ways, and to be numbered among the fundamental things that continue to apply, even as time goes by.

Lagers reconnect me to days of youth, but also to contemporary ideals of quality, because let’s face it: my father’s Wiedemann was a dog incapable of hunting apart from ingesting beverage alcohol at a low price point.

Do you have a favorite lager brewed by our metro Louisville brewers? If so, let me know.

Wikipedia explains today’s cover illustration. Schweik is seated to the right, and he’s enjoying a dark lager (maybe from Prague’s U Fleků brewpub) with his comrade.

The Good Soldier Švejk (Schweik) is an unfinished satirical dark comedy novel by Czech writer Jaroslav Hašek, published in 1921–1923, about a good-humored, simple-minded, middle-aged man who pretends to be enthusiastic to serve Austria-Hungary in World War I.