“When one thirsts for a glass of wine or a pint of beer, the brain gradually registers the order as a half-heard whisper. The volume is slowly turned up, creating a gentle, purring, reverberation throughout the nervous system. It seems a pleasurable massage at first, then becoming tenacious. You are in the hands of a higher authority that brooks no argument. It is desire, and the streetcar cannot leave its lines. Your destination is a rendezvous with a drink.”

— Michael Jackson, circa 2006

Last week: “Hip Hops: When Michael “Beer Hunter” Jackson came to Louisville in 1994 (part one).”

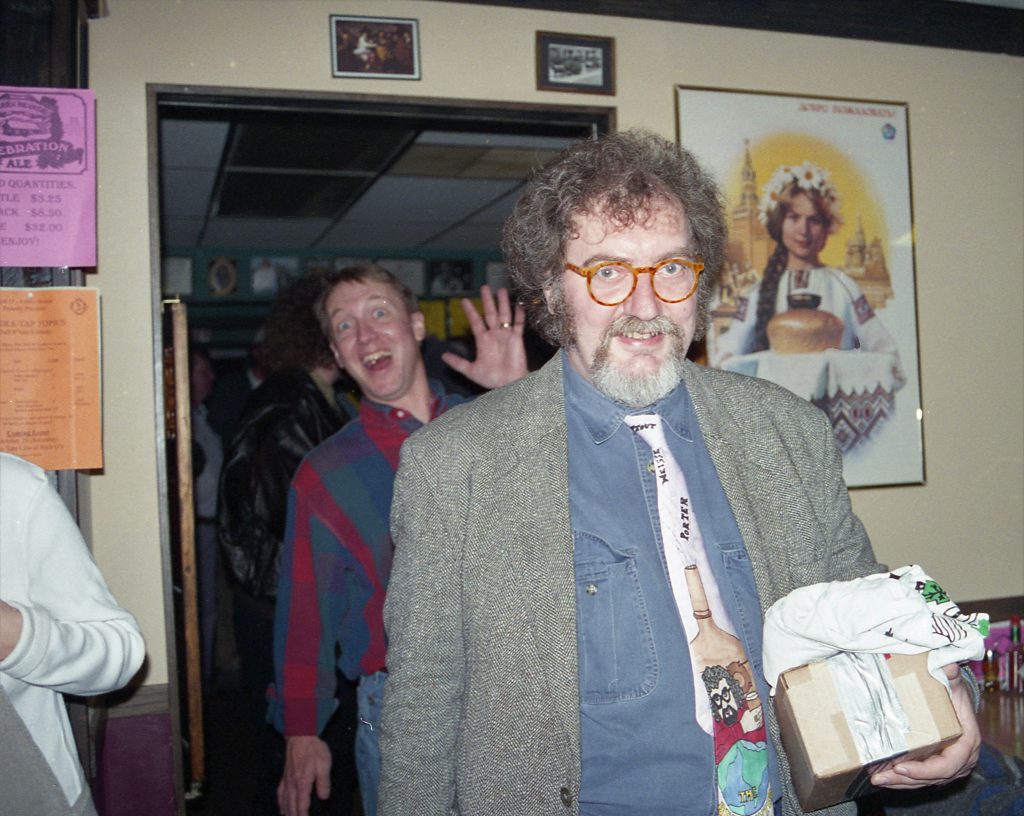

Pioneering British beer writer Michael “Beer Hunter” Jackson (1942-2007) spent a busy day in Louisville on November 19, 1994. Jackson was conducting a research tour of American microbrewing for a book he never published, although his findings later appeared as part of other writing projects.

No matter.

Jackson’s stops at Bluegrass Brewing Company, the Silo Microbrewery and Rich O’s Public House might seem like small beer 27 years later, but for those who were on the ground pushing local envelopes on behalf of better beer, Jackson’s stopover in Louisville was a taste of hoppy vindication.

In all honesty, in 1994 it was pastry stout in the sky to imagine there’d ever be 30 operational breweries in the metropolitan area, as exist today. However, we were sure there was room for more than two, and Jackson’s decision to include Louisville on his itinerary seemed like a harbinger of great things to come – and they have.

It cannot be overstated that better beer was a challenge to find hereabouts in 1994. If a bar anywhere in a 25-mile radius of Louisville tapped a keg of Pete’s Wicked Ale, it was big news, although by the time area beer enthusiasts found out, the keg likely would have been sent back to the wholesaler because it was a mistaken delivery. I mean, who’d want to drink a nasty dark beer like that?

In our contemporary era of vastly expanded choice, beers far better than Pete’s are available on draft at barber shops, nail salons and the tax preparer’s office. It’s only a matter of time until oil change joints and funeral homes jump on the bandwagon.

If you’d have informed me 27 years ago that one day there’d be six breweries in New Albany alone, I’d have judged you crazier than people thought I was, given my certainty as early as the 1980s that New Albanians would drink Märzen, India Pale Ale and beers soured on purpose.

Except enough of the townies drank them that we were able to pay the bills and have a little bit of spare change left over for a down payment on the bar tab. Drinking the profits never felt so good.

For the three co-owners of the embryonic Rich O’s Public House, later to become the New Albanian Brewing Company, the obvious highlight of Jackson’s late autumn day in Louisville came when he walked through the doors of our establishment, drank an Imperial pint of Sierra Nevada Porter, and seemed to enjoy himself amid an adoring public.

Upon his departure from the Public House ninety minutes later, Jackson issued a wry observation, one that inspired me to further efforts, and continues to prompt a big smile to this very day.

“I’ve been to many pubs in America, and I’ve never seen one quite like this.”

As he spoke these words, Jackson was looking at one particularly eccentric corner of our barroom, an area completed just a few months before his arrival. His body language would have passed into history without further comment if not for a serendipitous reunion six years later.

—

“Beer-drinking in the Soviet Union still has its folksy moments. Two Englishmen reported to the British beer-buffs’ newspaper What’s Brewing that they found a ‘well-hopped strong bitter ale, dispensed by water pump from wooden barrels’ at a café on the military road connecting Ordzhonikidze with Tbilisi.”

— from Jackson’s The New Word Guide to Beer (1977)

In 2000 I joined my friend Joey Burns in Denver for the Great American Beer Festival under the benevolent auspices of LEO Weekly, for whom I’d be writing an account of the yearly gathering.

We made it inside the huge downtown convention center for one of the afternoon sessions, with a few beer samples already under our belts. Eventually we found ourselves somewhere up on the mezzanine. I spotted beer writer Stan Hieronymus and leaned on a vacant table as we chatted.

Suddenly Stan asked me if I had brought a book to be signed.

With my face registering abject cluelessness, he motioned behind me – and there was Michael Jackson, settling in for another afternoon of beer talk and his then-current Great Beer Book.

Completely by accident, I’d managed to be at the head of a gradually lengthening line, and without a book to be autographed. It never occurred to me to simply buy a book. However, I had a GABF program tucked under one arm, and duly proffered it to Jackson as I reintroduced myself to Jackson and asked if he remembered the Public House.

He smiled in affirmation, adding that the monthly FOSSILS homebrewing club newsletters sent to him in London since his Public House visit were entertaining.

“You’re quite the polemicist,” said Jackson, pushing back the program as I blushed.

“Have I told you why your Red Room made such an impression on me?”

Then it came back to me. Jackson’s gaze back in 1994 had been fixed on the Red Room. Now it made sense.

The Red Room was, and remains, a small seating area by the bar in the Public House carved out of the drywall and drop ceiling, with one wall painted red and a massive three-part Soviet-era poster of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin on the wall, subsequently augmented with other examples of “red” paraphernalia.*

“No,” I replied. “What about the Red Room?”

Jackson put down his pen and began telling the story.

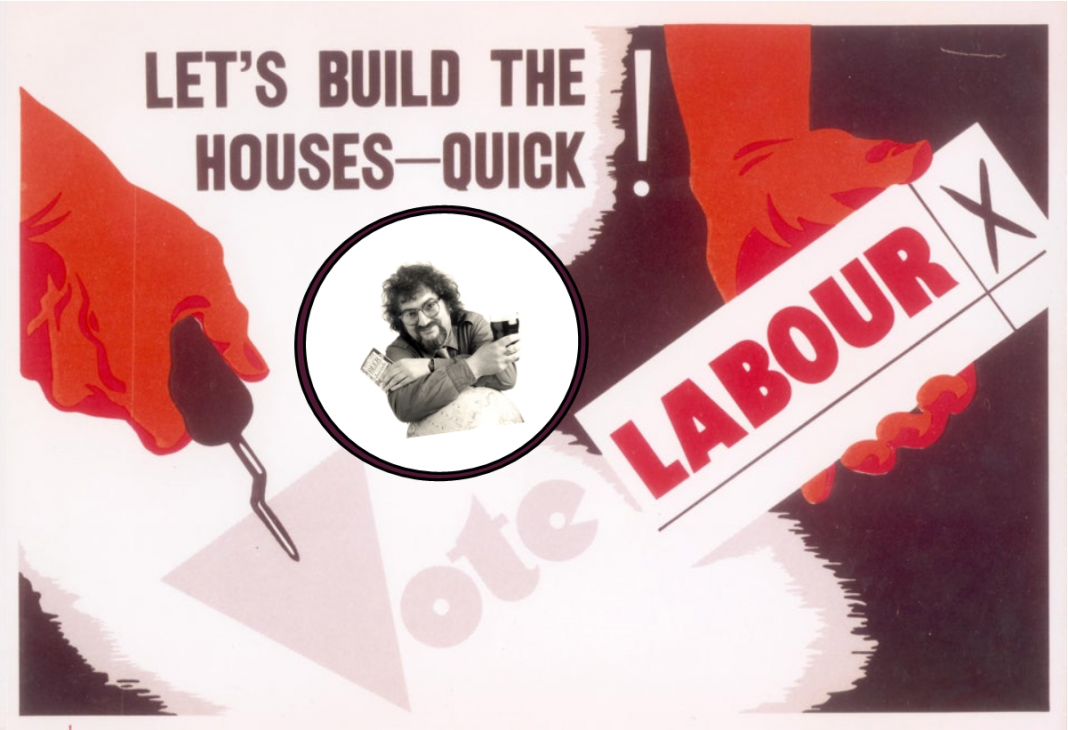

It began in 1945 with his earliest childhood memory at the age of three: The post-war British election campaign was underway. It ended with Labour’s sweeping victory, toppling Prime Minister Winston Churchill, for whom winning a war wasn’t enough to keep his job.

Jackson’s father, whom he described as the left-leaning family’s main political agitator, was at work, and so it was his mother – normally apolitical – who took young Michael to a rally for their Yorkshire constituency’s Labour candidate, an erstwhile journalist who was an unapologetic Socialist.

Jackson said he never forgot the rally’s uniformly red buntings and campaign banners. The candidate handily won the seat and began a long and distinguished career in Parliament, so long in fact that after the adult Jackson graduated from university in the mid-1960’s and began his own journalistic career, the same politician still held the seat he’d won in 1945.

Jackson was assigned to interview the aging politician, and learned the Member of Parliament had lived in America prior to the second war, where he had worked for…

“The leftist Louisville newspaper,” Jackson said to me. “What is the name of your leftist Louisville newspaper?”

By now I was becoming uncomfortably cognizant of a lengthening horde queued behind me, wondering who the hell I was to hold up their festivities.

Which newspaper in (dead, not red) Louisville would fit Jackson’s description of “leftist”?

He tried his best to jog my memory. “The newspaper’s owners were wealthy liberals,” he said, “and they sold the paper to a huge media company.”

Finally I blurted out: “The Binghams? The Courier-Journal?” Jackson came up out of his chair.

“Yes! The Courier-Journal, the Binghams – that’s it!”

The MP – the man whose campaign rally had been burned into Jackson’s earliest memory by virtue of the color red – had worked for the Louisville Courier-Journal and had spoken of the connection when interviewed by Jackson those many years before, thus providing the cognitive impetus for Jackson’s reaction to the Red Room in 1994.

Not even one person waiting behind me cheered when I collected my autographed program and made for the stairs. I was left in a daze to ponder the amazing confluence of a red-colored room, geography, politics, journalism, history and beer, with all these dots connected for my sole benefit by the world’s greatest beer writer.

There’d be a final opportunity to renew my acquaintance with Michael Jackson, in Indianapolis circa 2002, and he seemed to be doing fine during his appearance. Unfortunately, in December of 2006 Jackson revealed his long-term struggle with Parkinson’s Disease, which had been diagnosed a decade earlier. Sadly, the Beer Hunter died at 65 less than a year later, after suffering a heart attack.

At some point after Jackson was gone, it belatedly occurred to me that having neglected to record the MP’s name, it had been lost to my memory. The Internet intervened, and for the record, he was Sir Joseph Percival William (J.P.W.) Mallalieu (1908 – 1980), known as “Curly” Mallalieu, profiled here, here and here.

The Courier-Journal isn’t mentioned specifically in any of these sources, but Sir Mallalieu’s tenure at the Lexington Leader is cited, with an addendum that he worked at other newspapers in the Kentucky region for a period during the 1930s. That’s proof enough for me.

This coda from Jackson’s reminds us of what, in the end, really matters about beer.

“To clink glasses of a freshly made, seasonal beer, preferably in a pub or garden, with friends and perhaps new acquaintances, is a ritual that makes every participant feel good. We may not rationalize this at the time, but it gives us a sense of place in our common community and our time in the tides of life on earth. This is a way to value beer and treat it with respect.”

—

* As of October 2021, five years after my departure from NABC, the Red Room remains intact, albeit in altered form.

(Photo credits: For photos of Jackson’s Public House, the author’s collection.)