July 16, 17 and 18 are holy days in the pantheon of my beer travels, for it was during those three otherwise nondescript summer days in 1987 that four good friends, all hailing from Hoosierland, came together in Munich for a small sample of the prevailing Bavarian beer bacchanalia. Joining me were Bob, Barrie and my cousin Don.

On the surface, making plans to meet friends in Munich isn’t an uncommon occurrence. But to this very day, it remains remarkable to me that we coordinated our arrivals so efficiently. Given the circumstances of the era, as well as our relative inexperience traveling (except for Don, who was a seasoned pro), the manner by which our scheme came to fruition still elicits a smile.

Knowing we all would be roaming Europe during the summer of 1987, detailed trip planning began over the Christmas holidays in 1986. Barrie and I knew we’d be concluding a stay in Prague following our two-week tour of the Soviet Union and Poland. Our route to Munich was by rail from the East Bloc, which sounded a tad ominous.

Bob, who was on his first trip to the continent, was coming from far-off Spain and Don, if memory serves, from Italy. As was his habit, Don had booked a single room at a favorite local haunt, while the rest of us made advance reservations together in a triple occupancy room at a hotel somewhat near the Munich Hauptbahnhof (main train station).

We each knew when to arrive in Munich, as well as where we’d be staying, and yet in those far-off and seemingly primitive times, lacking e-mail and mobile phones (what it took just to place an international phone call from a communist country merits a column all to itself), and with each member of the quartet having been on the road for quite some time prior to the projected Munich gathering, a considerable element of uncertainty was palpable.

In essence, given our dissolute proclivities, could we remain sufficiently sober, avoid unexpected transportation delays, be where we were supposed to be, and show up on time?

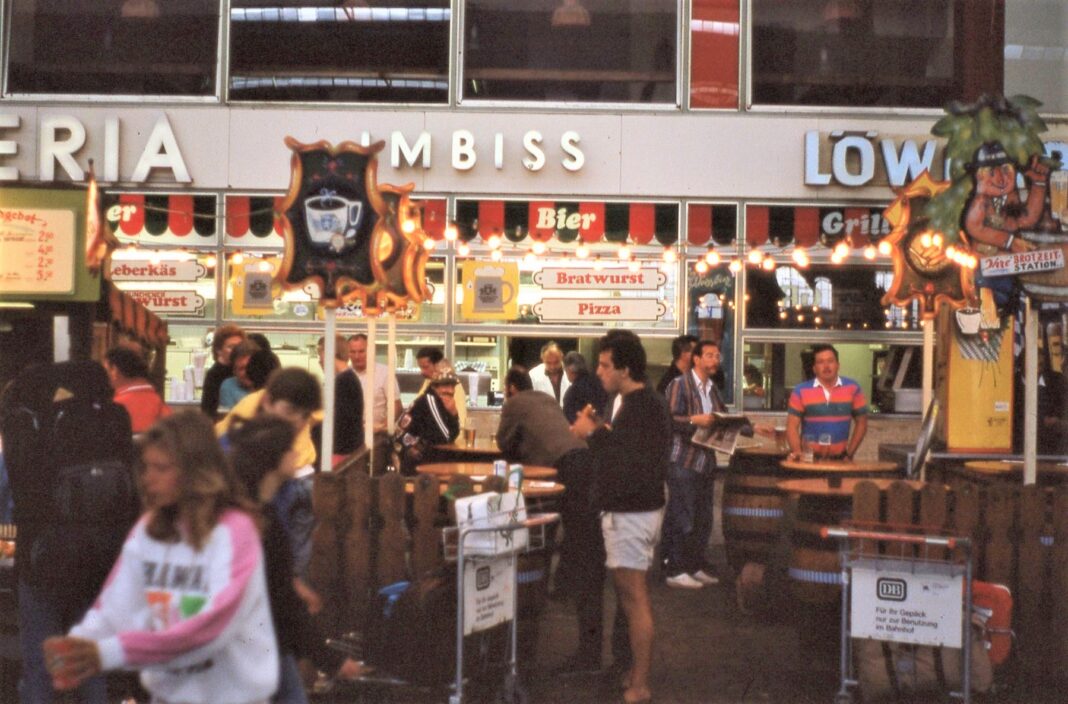

Happily, we could. The rendezvous went off without a hitch. Barrie and I arrived at the Hauptbahnhof from Prague and found Don idling with beer in hand at the fabled Gleis 16 Imbiss, and after a leisurely round, we walked a few blocks and there was Bob, waiting at the hotel.

Happily, we could. The rendezvous went off without a hitch. Barrie and I arrived at the Hauptbahnhof from Prague and found Don idling with beer in hand at the fabled Gleis 16 Imbiss, and after a leisurely round, we walked a few blocks and there was Bob, waiting at the hotel.

This famous Imbiss (snack counter) at the foot of Gleis (track) was a classic venue at the Hauptbahnhof. It wasn’t in the travel guidebooks, and has long since been supplanted by remodeling, modernization and gentrification (with more on the way). Gleis 16 Imbiss wasn’t all that much even in its heyday, but during the 1980s this simple, functional train station concession stand was a genuine Munich destination for discerning budget travelers the world over.

There were two long windows with outside counter space, plentiful tile and stainless steel, utilitarian beer taps, kitchen equipment for preparing basic nibbles, and several customarily greasy, though by necessity diligent, employees in white shirts, sometimes augmented with blue smocks.

Arranged in front of the Imbiss were a handful of regular standing-room-only cocktail tables, and also some that resembled smaller, elongated versions of the wooden telephone wire spools that used to litter backyards in the Georgetown of my youth.

Standing at these tables by morning, evening and night were locals, tourists, commuters, vagrants and assorted hangers-on, the majority of them savoring the Imbiss’s only true specialties: Cool Hacker-Pschorr golden lager and a portion of Leberkäse, a high-quality form of all-meat quasi-bologna made from corned beef, pork and bacon, cut from a warm deli-sized square loaf, the weighed, priced, and served with a crusty roll and plenty of mustard.

The Imbiss at Gleis 16 never disappointed, representing old-fashioned egalitarian functionality for the city’s everyday transit users, as well as short-term visitors like us, for whom it was a fine and refreshing perch to observe life’s rich pageant.

The Imbiss at Gleis 16 never disappointed, representing old-fashioned egalitarian functionality for the city’s everyday transit users, as well as short-term visitors like us, for whom it was a fine and refreshing perch to observe life’s rich pageant.

In retrospect, it can be surmised that the Cold War helped preserve older ways in Central Europe. When it ended, and the planetary internet revolution arrived, change came quickly.

Nowadays, larger urban train stations in Europe have been rebranded upscale in the fashion of airports. Like so many aspects of “older” Europe, I’m just happy to have experienced tastes of the way things were, like at Gleis 16.

—

Our stories about Munich in 1987 have been suitably embellished over the decades, and yet there remains a core of truthfulness to the anecdotes.

There was my brief episode of disgruntlement at having to leave a beer hall at an hour I considered to be far too early, and a stern worker’s gentle suggestion to take the argument elsewhere.

There was Don’s “Bavarian Exit,” shortly to be recounted.

There were liter steins of beer, various and sundry sausages, Deutschmarks and Pfennigs, aspects of unfathomable etiquette that became second nature before the last glass was poured, and a constant flow of conversation, information and education.

Admittedly, had I known then what I know now, we’d have avoided Munich entirely and gone instead to Bamberg, but given our remedial state of beer knowledge, it is likely that the choice of Munich was all for the best. We might not have fully grasped Rauchbier and Kellerbier.

German beer traditions can be pleasing so long as it is remembered that much of what Americans know about Germany actually pertains to Bavaria, and much of what they know about Bavaria actually applies to Munich alone.

For example, “beer halls” in the sense of the Hofbräuhaus generally do not exist in matching scale outside the city of Munich. Fortunately for us, in 1987 a beer hall even larger than the Hofbräuhaus was our home away from home for three glorious evenings. It was called Mathäser Bierstadt (“beer city”), and was tied to Löwenbräu.

The Mathäser was cavernous, filled with nooks, cellar, byways, gardens, banquet rooms and snugs, and it was decidedly grittier than the Hofbräuhaus – perhaps less attractive for well-heeled tourists, but comfortably down-home, with an earthier composition of native German barfly that we absolutely adored.

At its post-WWII peak, there were 5,335 seats at the Mathäser. Is it possible to be a dive bar with room enough for 5,335 drinkers?

The Mathäser as we experienced it in 1987 was built in 1892 on the site of a previous beer hall and brewery. Löwenbräu bought the premises in 1907, and the brewery was closed in 2015. Amid chaos at the conclusion of World War I, the short-lived Munich Soviet Republic actually was headquartered at the Mathäser, confirming the usefulness of the city’s larger beer halls as event venues.

Wikipedia’s summary is impeccably understated: “After the revolution was crushed, the Mathäser returned to its original function as a beer pub.”

Our Munich nights in 1987 were absorbed with wide eyes and a sense of wonderment. For a beer- and history-loving Hoosier just shy of his 27th birthday, roaming Europe for the second time, Munich was the epitome for me. It was a far better grade of Disneyland with ubiquitous mugs of foamy lager and all the sausages, sauerkraut and potatoes one cared (or could afford) to eat.

And the Mathäser Bierstadt was tops. It felt like the 1950s, or so I imagined. Unfortunately, the Mathäser perished in 1996. A few years later the site was transformed into an ultra-modern cinema and entertainment complex. I walked past it in 2004 and bowed in reverence for what used to be. The last time I was there during its actual existence was in 1995, and even then the beer hall seemed rather exhausted, its arteries hardened, even if we did our level best to enliven the proceedings.

Dubbed American movies probably are showing now, and outside the cinema, you’ll see imported Miller and Corona throughout the city. The Oktoberfest lagers become ever lighter, and beer tastes colder on each trip. There’s a Hofbräuhaus franchise in Newport, Kentucky, and more than 20 others throughout the world.

The memories are fond, indeed, and now increasingly balanced by melancholy.

—

As Friday evening’s session at the Mathäser Bierstadt neared its conclusion, Don rose, tottering and grinning. He disappeared. Later he insisted that his parting had been effusive and memorable, a valedictory oration of Shakespearean vintage, and surely among the most eloquent ever uttered in such an honorable establishment.

I’m here to tell you that he never said a single word.

I’m here to tell you that he never said a single word.

Our colleague might have been going to the WC, but soon enough we assumed Don simply had returned to his lodging (which in fact he had), and so we ordered a final round of tasty liter-sized Löwenbräu lagers just ahead of last call.

By this time, the resident oom-pah band had completed its 13th and final rendering of “Waltzing Matilda” for the sodden Aussies in the corner, and the massive nightly clean-up was beginning.

By this time, the resident oom-pah band had completed its 13th and final rendering of “Waltzing Matilda” for the sodden Aussies in the corner, and the massive nightly clean-up was beginning.

I was next in line to (verbally) capitulate and crawl back to the room, leaving Barrie and Bob to have one last beer at one of Munich’s many bars, which stayed open late — or early, depending on one’s perspective.

Exactly what happened next remains foggy, but still is the stuff of legend. Barrie was uncommonly thirsty, and though outweighed, Bob kept pace. One beer turned into several, and a single establishment became two, perhaps even three.

At some point there was arm-wrestling, feats of strength, wagers and a drunken local fireman dubbed The Munich Stud. Seemingly all that was missing was a Weisses Schloss (White Castle) for sustenance as the morning newspaper was being delivered.

At some point there was arm-wrestling, feats of strength, wagers and a drunken local fireman dubbed The Munich Stud. Seemingly all that was missing was a Weisses Schloss (White Castle) for sustenance as the morning newspaper was being delivered.

All in all, I was very happy to have slept through the endurance contest.

A projected Saturday field trip on Saturday to the town of Dachau and its sobering concentration camp was cancelled. The group finally reconvened later in the day, making a brief appearance at the Hofbräuhaus before realizing that we’d left our hearts at the Mathäser, returning there for more groaning platters of rouladen, Spätzle and dumplings, though somewhat less copious portions of Löwenbräu.

Barrie, Bob and I said our goodbyes to Don on Saturday night upon exiting the Mathäser well before last call. He departed Munich on Sunday morning to resume his habitual European travels, leaving the three of us to begin the next phase, with a train to Maintz and a Rhine River boat ride.

Next week: We’re not the only ones to remember the Mathäser Bierstadt with fondness.

Roger Baylor is an educator, entrepreneur and innovator with 40 years of hands-on experience and expertise as a beer seller, restaurateur and commentator. As the co-founder of New Albany’s Sportstime Pizza/Rich O’s Public House (which later became New Albanian Brewing Company) in the 1990s and early 2000s, Baylor played a seminal role in Louisville’s craft beer renaissance. Currently he is the beer director at Pints&union in New Albany and Common Haus Hall in Jeffersonville. Baylor’s “Hip Hops” columns on beer-related subjects have been a fixture in F&D since 2005, and he was named the magazine’s digital editor in 2019.

Roger Baylor is an educator, entrepreneur and innovator with 40 years of hands-on experience and expertise as a beer seller, restaurateur and commentator. As the co-founder of New Albany’s Sportstime Pizza/Rich O’s Public House (which later became New Albanian Brewing Company) in the 1990s and early 2000s, Baylor played a seminal role in Louisville’s craft beer renaissance. Currently he is the beer director at Pints&union in New Albany and Common Haus Hall in Jeffersonville. Baylor’s “Hip Hops” columns on beer-related subjects have been a fixture in F&D since 2005, and he was named the magazine’s digital editor in 2019.