“Because when I read, I don’t really read; I pop a beautiful sentence into my mouth and suck it like a fruit drop, or I sip it like a liqueur until the thought dissolves in me like alcohol, infusing brain and heart and coursing on through the veins to the root of each blood vessel.”

― Bohumil Hrabal

For Christmas this year I bought myself an informative work of non-fiction: Communist Czechoslovakia 1945-1989: A Political and Social History, by Kevin McDermott. It’s an academically-oriented overview, and it wouldn’t surprise me if beer isn’t mentioned at all, although brewing remained a major social and economic component of Czechoslovak life behind the Iron Curtain. It has been estimated that by the late 1980s, Pilsner Urquell alone accounted for 10% of the country’s hard currency exports.

For me, the consumption of Pilsner Urquell produces predictable responses. First there’ll be a slide show in my head, featuring images from the times I’ve visited the Czech and Slovak lands. Then there’ll be an urge to listen to “Má vlast” (My Fatherland), the tone poems by Czech composer Bedřich Smetana. Finally, and decisively, a need to read overtakes me.

During the 1980s, Milan Kundera arguably was communist-era Czechoslovakia’s best known author in the West, primarily because he fled his home country and began writing from Paris, often in French. Kundera’s most famous novel was The Unbeerable Erring of Lite-ness, or maybe it was The Unbearable Lightness of Being. I like the first title better, but the second identifies the 1988 cinematic adaptation of Kundera’s book, starring Daniel Day-Lewis.

Recently I pulled a volume from my shelf in the study as a Czech cultural refresher: Mr. Kafka and Other Tales from the Time of the Cult*, a collection of short stories by Bohumil Hrabal (1914-1997), who is unknown in America but surely merits a place in the upper echelon of 20th-century Czech writers. The stories were originally written during the years immediately following WWII, when a Stalinist variation of Communism was being grafted onto postwar Czechoslovakia.

Recently I pulled a volume from my shelf in the study as a Czech cultural refresher: Mr. Kafka and Other Tales from the Time of the Cult*, a collection of short stories by Bohumil Hrabal (1914-1997), who is unknown in America but surely merits a place in the upper echelon of 20th-century Czech writers. The stories were originally written during the years immediately following WWII, when a Stalinist variation of Communism was being grafted onto postwar Czechoslovakia.

Hrabal was a fascinating character, born in Brno to an unwed mother as a citizen of the Austro-Hungarian empire, raised in the interwar period during the free Czechoslovak Republic, then surviving successive, repressive Nazi and Communist eras to die in the reconstituted modern Czech Republic, albeit minus Slovakia. The writer outlasted them all, and followed his own muse to the very end.

Even more so than fellow writer (and playwright, as well as eventual politician) Václav Havel, who briefly worked in a brewery as “punishment” for dissident activities, Hrabal’s whole life seemed to embrace beer. His mother and stepfather met in the Polná brewery (Pivovar Polná), and in honor of this occurrence, the writer is buried in an oak coffin bearing the same brewery’s inscription.

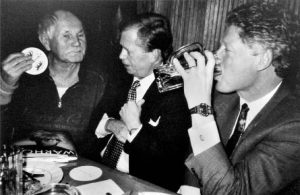

As an artist and raconteur, Hrabal is synonymous with the proud traditions of Czech pub life. The photo shows Hrabal, Havel and Bill Clinton at Prague’s U Zlatého tygra (“At the Golden Tiger”) tavern, Hrabal’s favorite Old Town pub in Prague. Such was the writer’s loyalty to this establishment that to this very day, it devotes a section of its web site to him.

As an artist and raconteur, Hrabal is synonymous with the proud traditions of Czech pub life. The photo shows Hrabal, Havel and Bill Clinton at Prague’s U Zlatého tygra (“At the Golden Tiger”) tavern, Hrabal’s favorite Old Town pub in Prague. Such was the writer’s loyalty to this establishment that to this very day, it devotes a section of its web site to him.

Hrabal, who was a firework of ideas and witty solutions, and who lived the glory and downfall of the cultural boom of the sixties, was surrounded by the best representatives of the intellectual and art world. This place was the intersection of the visits and visitors from all the Word. Everyone wanted to speak to Hrabal and look into the places where the plots of his novels are set.

From Hrabal’s time to the present day, the only beer U Zlatého tygra has served is draft Pilsner Urquell. One time in 1995, seven of us stopped at the perpetually packed tavern, despairing of our chances of finding a place to sit as a group. We spotted one man holding down a table, and I tried to ask him in gibberish Czech whether the seats were taken. He interrupted in perfect English and invited us to sit.

No, it was not Hrabal. Damn the bad luck. Rather, our new friend was a native of Prague and a maker of documentary films, who had fled Czechoslovakia many years before but returned after the fall of communism. The filmmaker began explaining the history of U Zlatého tygra, eventually asking the man behind the counter if he could take us into the basement.

Off we went, threading down two flights of stairs to the cellar, where several dozen kegs of Urquell were stacked around an air conditioner of sorts, which brought the temperature down a few degrees from the subterranean norm. Back at street level in the cozy interior, we proceeded to drain round after round of delicious Urquell as I daydreamed about Hrabal or Havel popping in for a quick one.

Returning briefly to Havel, his two-person play Audience is wonderful. In it an artistic, city-dwelling enemy of the totalitarian state, who has been sent to the hinterlands by the regime as punishment to serve a term as manual laborer in a brewery, is called for a meeting with the boss. He must endure the chief’s ramblings of his boss, which become increasingly incoherent as he quaffs the brewery’s wares, hilariously sinking into inebriation while haplessly pretending to interrogate the urban exile.

The cover photo is of our gang at U Zlatého tygra in 1995. I have no idea what happened to the filmmaker. Pilsner Urquell is still distinctive and reliable, and I never hesitate before exploring the rabbit holes it sends me down.

—

* It must be noted that Hrabal’s usage of “cult” is not to be confused with American worshippers of Goose Island Bourbon County Stout.