Arthur Frommer died last week at the grand old age of 95. We never met, not even once, but it remains my fervent conviction — absent hyperbole or exaggeration — that Frommer changed my life.

(True, the beer writer Michael Jackson also altered the course of my existence, but I was fortunate to have a few actual conversations, and beers, with him.)

Jackson’s book The World Guide to Beer kickstarted my interest in beer and brewing. Frommer’s Europe on $25 a Day sent me to the places where beer remained at its best during the formative period of my twenties, when American beer was struggling to recover from decades of abuse.

To me both these books are sacred texts.

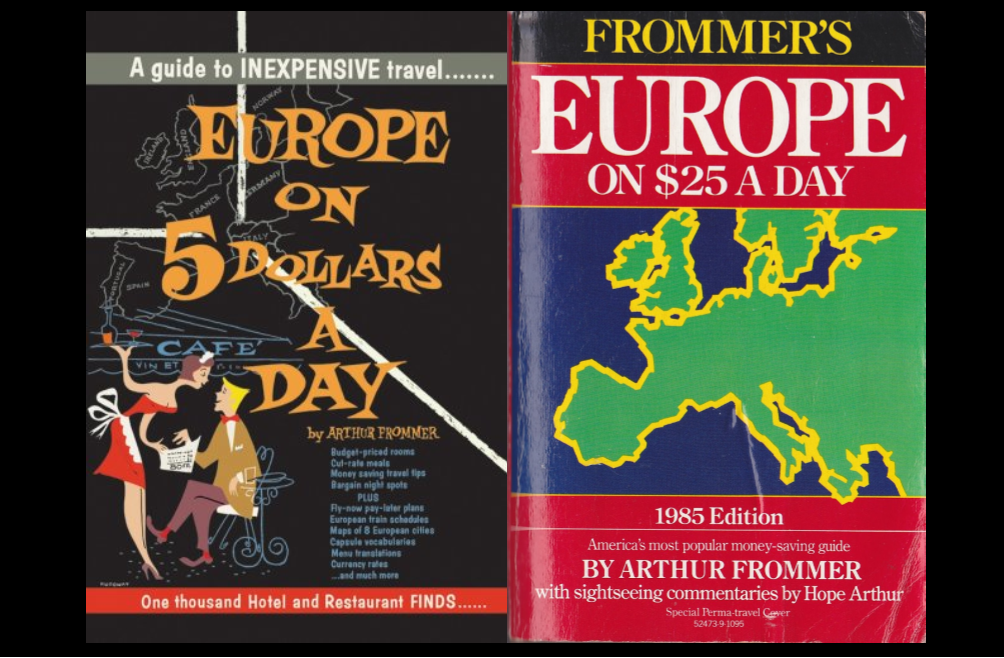

Pauline Frommer reported her father’s passing at their website (cover photo credit). He conceived the notion of counseling travelers while stationed in Europe during the late 1950s, and continued working well into his 90s, such that for the longest time I was able to raise a toast to Frommer’s health upon returning to Europe.

Henceforth, each time back I’ll drink to his memory. I cannot thank him enough.

It is with deep sadness that I announce my father, Arthur Frommer, founder of the Frommer’s guidebooks and Frommers.com, passed away today at the age of 95, at home and surrounded by loved ones.

Throughout his remarkable life, Arthur Frommer democratized travel, showing average Americans how anyone can afford to travel widely and better understand the world. He published the revolutionary Europe on 5 Dollars a Day, the first in the Frommer’s guidebook series that continues publication today; he was a prolific writer, TV and radio host, and speaker; and in 1997, he was the founding editor of Frommers.com, one of the world’s first digital travel information sites.

I am honored to carry on his work of sharing the world with you, which I proudly do with his team of extraordinary and dedicated travel journalists around the world. We will all miss him greatly.

Frommer’s pivotal insight was that European travel needn’t break the bank, and what’s more, eschewing the financial burdens of the “Grand Tour” ensured a better overall experience. So it proved to be. Where would I be had sheer serendipity not brought me to Frommer just when I needed his budget travel advice the most?

—

In 1983, I was asked by the late Bob Youngblood, a former high school English teacher, to accompany him as a second chaperone on a student trip to Europe the following year. The price seemed reasonable at $1,600 for nine days, with airfare, hotels, bus and most meals included. I responded affirmatively.

A few months later, I was strolling past the travel section in the library when a title caught my eye: Europe on $25 a Day, by Arthur Frommer.

As ever mathematically challenged, I shook my head with disbelief. Was it a misprint? Could it really be true? Skeptical, I checked out the book, took it home, poured a beer, and started reading it cover to cover. Eventually a pocket calculator was produced.

The earth fairly shook. With clear and reasonable tips, I was taught how to do Europe the right way, and for a far longer duration than nine days.

Frommer became my hero. He insisted that travel could be educational, offer rare glimpses into different worlds. His advice on the nuts and bolts of budget travel technique was relentlessly informative, effortlessly evocative and consistently pragmatic.

- Always think like a European traveler, not an American, and like a local resident, not a visitor.

- Don’t expect things in a foreign country to be the same as home, and expect to pay more when they are.

- Think, plan, and accept the available bargains when they arise.

- Don’t eat every meal in a restaurant. Check out a market, pack a salami, buy a loaf of cheap crusty bread, and have a picnic.

- Walk, ride the bus, rent a bike.

My brain was hard-wired for the humanities and history, and yet the comparative sums quickly became persuasive. At $25 per day, my $1,600 nest egg properly budgeted the Frommer way came out to 36 days, not nine. If I were to postpone the epic jaunt for a while, leaving even more time to save money, the trip might last three months, not nine days.

For the next year and a half, my European travel obsession escalated, fed by a steady diet of travel books, magazine articles and PBS documentaries. Thomas Cook rail schedules were studied, and European history (already my favorite) devoured with renewed zeal.

Plans were jotted, expanded, revised, discarded, and brought back from the waste paper basket. I acquired a Pentax K-1000 camera boasting nary an automatic feature and learned to use it, just barely.

By the spring of 1985, with departure nearing, the rough outline of a three-month journey had settled into place. Then it all happened. The trip wasn’t perfect, and as much as Frommer did to show his readers the ropes, genuine learning occurs only after failures on the ground; if you haven’t failed, you haven’t tried — and this was exactly the lesson I needed to learn.

At times, clichés are all we really have, so I can attest that returning in August of 1985, passing through customs in Chicago, I was transformed and definitely knew things weren’t going to be the same for me ever again. Once would not be enough. There’d have be another expedition, and so how could I arrange my life during what might be a two-year wait, until my funds were sufficiently healthy to enable the next escape?

I didn’t know the details, only the imperative, and it has remained part of my life ever since. Upon arrival in Split, Croatia in early November this year, I established a daily needs perimeter, grabbing my vial of Woolite and proceeding to the bathroom sink to wash my t-shirt, underwear and socks, then drip-dry them in the shower stall before hanging them in the armoire to air-dry and be worn again the following day if necessary.

Every bit of this routine was taught to me by Arthur Frommer.

Far more than high school and college graduation dates, the year 1985 marked the first great dividing line in my life. There is what came before the European journey, and what happened after it.

I bet Frommer heard variations of this refrain hundreds of times, and I trust he was proud to have been an enabler of this magnitude. He was a teacher, and teachers want to know that their students learned something and are passing it along. It’s the whole point, isn’t it?

Later I’d experience numerous other narrative junctures involving the usual suspects like thru-ways, dead ends, lovers, careers, wins and losses; all the things that go to make up a life. There have been 45 more trips to Europe since 1985, with another coming in February 2025 to North Macedonia and Albania, eloquently bearing out the extent of the obsession that blossomed with Frommer’s benevolent assistance.

—

What did it all mean? It’s question I’m still trying to properly assess, and in many ways the available answers are a tad embarrassing.

Allow me to explain.

At age 64, I can see far more clearly. In spite of the many qualifications and evasions available to me, the mere fact that I took a trip to Europe in 1985 speaks to a level of privilege, not privation. It testifies to how lazy and formless I’d been up to that point.

In 1942, my 17-year-old father literally ran away from home to fight in a world war, and I was spared this tough choice. He and I didn’t always agree, but my parents worked hard and sent me to university — for what became a philosophy degree, qualifying me to tend bar and read a lot. I didn’t go to work in a sweat shop at age 12 or endure domestic violence, and few hard decisions were mine to make.

In short, I was incredibly fortunate.

It was easy muddling through my youth, and I had ample time to wait until my early twenties to decide at long last to get my act together, hence the Euro quest, purely an elective course, as designed to “find” myself. Most humans on the planet don’t have such a luxury, and yet this life is the only one I’ve ever had; all I can do is live it to the best of my ability and try to be useful along the way.

Europe in 1985 is where and when I grew up, insofar as I’ve ever grown up, which is a highly debatable proposition.

Europe was the exact opposite of my party-hardy undergraduate experience, and far more of an advanced educational seminar than a non-stop bacchanal.

Europe is where things began making sense to me, and honestly, I was as surprised as anyone by the lightbulb’s illumination. Somewhere inside me actually reposed the slumbering genes I needed to plan ahead, work hard, save money, and challenge myself.

This is the ultimate point, because at first, I got it completely backward. I kept thinking that a tenure in Europe was required to gain the experience necessary for growth and self-knowledge, and of course being there proved to be very significant, except that what affected me the most, more so than three months riding trains, was the two-year period preceding the trip.

Yes, Frommer changed my life because discovering Europe changed my life. What I didn’t notice at the time was my life changing in order to get to Europe. Finally, I cared about something, and finally, out of nowhere, emerged a work ethic.

Who’d have guessed it? Here are three personal legacies of Euro ’85.

Food, cooking … and beer.

Moussaka, clam sauce, blood sausage, Wiener schnitzel, herring and beef tartare are just a few of the culinary high points of Euro ’85. I’d never encountered foods like these, and the fact that even a tourist on a tight budget might still be able to order them was impressive.

Coming from a background of largely flavorless meat and potatoes, this exposure was revelatory, but since few of these meals were readily available back home, it was time to take cooking seriously. The only way I’d be able to have the dishes I wanted was to cook them myself, and while much has changed since then, cooking remains a rewarding pursuit.

Meanwhile, beer as a career wasn’t yet apparent to me, and my first European trip wasn’t about compiling or rating brands and styles. My beer understanding remained decidedly imperfect afterward. However, experiencing first-hand the prevailing beer culture in places like Germany, Austria and Ireland was absolutely invaluable, and it obviously informed the progress of the impending Rich O’s/NABC Public House.

Language.

In 1985, I’d been exposed to almost as many languages as countries, but the problem with constant movement was a reduced opportunity to make sense of them in any detail. Upon return, I vowed to learn a European language, and began stockpiling books, instructional cassettes and videos.

Alas, it came to very little in the end, and I still lack proficiency in a second language. However, I know a few words in two dozen languages, and prior to my second journey in 1987, managed to teach myself the Cyrillic alphabet, which made Moscow’s subways navigable.

Urbanism’s lure.

I grew up in the Southern Indiana countryside, then went to Europe for the first time and spent nearly all of the trip exploring cities. I’ll grant that it took a while for these urban lessons to be absorbed, but the conversion was genuine and has proven lifelong.

These days, it seems to me that I inhabit a neighborhood (New Albany) of a larger city (Louisville), albeit it without all of the amenities in infrastructure that made European city life what it was, and remains.

Shouldn’t I be able to board a bus, switch to the subway, and be in downtown Louisville in minutes without once considering the use of my car? Why our endless sprawl? Can’t we fill in those tragic empty spaces where the downtown buildings used to be? Mowing the lawn only wastes time better spent planning the next trip.

Thanks again, Arthur Frommer. You helped make me what I am today, for better or worse. The older I get, the more normal my Frommer-led European interlude in 1985 appears.

It’s the long trip since that has been so damned strange.

—

Previously at “Hip Hops”:

Hip Hops: A consideration of beer in Croatia, as opposed to Yugoslavia

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with