Greeting from Minneapolis, where we’re spending my birthday week. The Beer Hall at Surly Brewing is a ten minute walk from our Airbnb. There’ll be a couple of Twins games, Hmong cuisine and the Minneapolis Institute of Art. As for this week’s beer column, it is inspired by a question I’ve received several times since the launch of Common Haus earlier this year. As always, thanks for reading.

I remember the day, many years ago, when my German friend drew a line in the sand.

We were debating the merits of a blueberry chocolate stout, long before such hybridized stylistic creations became the daily norm in craft beer.

“It just isn’t right,” he said.

“According to the Reinheitsgebot, you must use only grain, hops and water to make beer—not berries, chocolate, pumpkins, chili peppers, or coffee!”

My German friend was correct, insofar as he understood the present day applicability of the Reinheitsgebot, or Bavarian Beer Purity Law of 1516.

However, he also was mistaken, for at least two good reasons.

For starters, cultural relativism in beer has existed since the beverage’s ancient beginnings. The planet’s brewers have always experimented with a multitude of fermentable materials, additives and flavoring agents, based on their specific locale and available raw materials. Barley and hops might be the best choices, but they’re not the only ones.

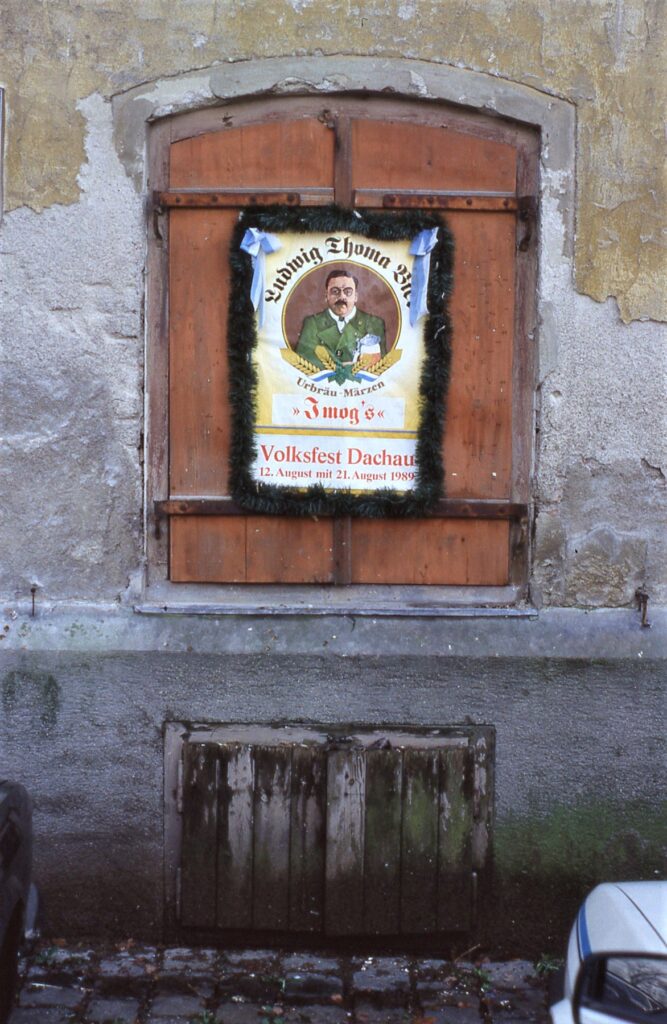

Perhaps more surprisingly, the Reinheitsgebot itself seldom measures up to close scrutiny in exactly the way its adherents claim. As an example, the Bavarian Beer Purity Law of 1516 wasn’t widely known by the name “Reinheitsgebot” in non-Bavarian regions of Germany until the time of the post-WWI Weimar Republic (1919-1933).

Long before, at its inception 500 years prior to the Weimar period, the beer purity law was a pre-industrial omnibus regulatory document. It addressed the beer market in broad terms by the prevailing standards of the day, defining competitive terms, fixing prices, and establishing taxation rates.

During a historical era when one’s “daily bread” often meant “daily minimum for survival”, the Reinheitsgebot delineated grains suitable for brewing (barley) and those better reserved for baking (wheat and rye), the intent being to keep these grains in their respective spheres of preparation, and to ensure the Bavarian royal subjects were both fed and watered.

But today we know the Reinheitsgebot only for the small section specifying the permissible brewing ingredients of barley malt, hops and water (modified subsequently to include a handful of exceptions, including the use of wheat and rye, perhaps just so long as there was plenty set aside to bake bread).

Significantly, beer’s absolutely indispensable ingredient of yeast wasn’t mentioned in the Reinheitsgebot, as fermentation was only superficially understood (if at all) until the advent of the microscope.

Specific malting and brewing processes also elude the Reinheitsgebot, like purposeful souring (Berliner Weisse), or ways of malting, as with Rauchbier’s smokiness deriving from wet barley being dried over a fire.

Moreover, history almost always proves to be messier than we’d like, and resistant to over-simplification.

Only after the creation in the 1870s of the new Prussian-dominated nation subsequently known to us as Germany did the Reinheitsgebot possess any meaning for brewers outside the newly absorbed former Bavarian kingdom.

The purity law eventually was adopted for use in the whole of unified Germany, but it wasn’t implemented or recognized to any great degree nationwide until the early years of the 20th century, when the German brewing community began to see the benefit of using the Reinheitsgebot to market their beers against foreign competition, and if this wasn’t enough, to block imports outright.

Decades later, in 1984, the European Court scotched this protectionist aspect, ruling that Germany couldn’t deploy the Reinheitsgebot’s prohibition against the use of corn and rice as a means of excluding foreign beers like Corona and Budweiser.

It’s another question entirely as to why any self-respecting German would drink either of them, then or now; however, as a fascinating aside, and contrary to conventional wisdom, some researchers believe that German brewers arriving in America in the 1800s came already equipped with the know-how to use adjuncts like corn and rice because they’d been using them in Germany (although presumably not in Bavaria).

If this assertion is accurate, a great many blithe assumptions are in need of re-examination, including some of my own.

So, having all too happily deconstructed the Reinheitsgebot all the way down to the studs, and sold off the copper pipes for scrap, is there anything left of value to build back? Does the Reinheitsgebot still matter?

I think so, although to a certain extent pro-purity law arguments are circular. For at least a century, maybe longer, Bavarian brewing (and later beer making in all of Germany) evolved in conjunction with technological innovation to create styles of beers specifically suited to the Reinheitsgebot’s stipulations.

Consequently (and unsurprisingly) these styles benefit from adhering to the beer purity template. In essence, their defining characteristics incorporate adherence to the Reinheitsgebot.

As an example, consider the traditional springtime style known as Helles Bock (or Maibock), a strong, pale lager ideal for springtime. An all-barley-malt Maibock at around 6.5% – 7.2% abv is both joyfully complex and perilously quaffable.

But cut a few corners, use inexpensive adjuncts like sugar (prohibited by the Reinheitsgebot), reduce the lagering time and spend more on marketing, and you’re left with something like malt liquor, which is ubiquitous in Europe nowadays, usually identified as “strong lager,” and often blamed as fuel for sporting event hooliganism.

One is elegantly constructed, the other purely functional. There is room in the stylistic panoply for both, but it’s hard for me to imagine an all-barley “malt liquor” (negating rapid high octane swallowing) or an adjunct-choked Maibock (muting the contemplative qualities that enable its nobility).

Overall, the Reinheitsgebot is instructive. It provides illumination about Germany’s work habits, local beer markets, consumer preferences, and why all-malt pilsners differ markedly from corn- and rice-augmented versions.

But in the final analysis, just because one geographical region possesses such a law, it should neither be taken to imply that such rules matter elsewhere, nor taken to preclude the use of other fermentables, spices, flora and even the occasional bi-valve as part of the brewer’s arsenal of tricks.

Wait: bi-valve?

Yes, it’s true; in English brewing history, certain stouts not only have accompanied oysters, but contained them – and at least one, from Bushy’s on the Isle of Man, still does.

As for that blueberry chocolate stout, my German friend’s denunciations on grounds of Reinheitsgebot abuse were duly noted, although surprisingly, he didn’t refuse the sample I offered.

I could have sworn I saw the shadow of a smile cross his face, although it might have been a trick of the light.

Roger Baylor is an educator, entrepreneur and innovator with 40 years of hands-on experience and expertise as a beer seller, restaurateur and commentator. As the co-founder of New Albany’s Sportstime Pizza/Rich O’s Public House (which later became New Albanian Brewing Company) in the 1990s and early 2000s, Baylor played a seminal role in Louisville’s craft beer renaissance. Currently he is the beer director at Pints&union in New Albany and Common Haus Hall in Jeffersonville. Baylor’s “Hip Hops” columns on beer-related subjects have been a fixture in F&D since 2005, and he was named the magazine’s digital editor in 2019.

Roger Baylor is an educator, entrepreneur and innovator with 40 years of hands-on experience and expertise as a beer seller, restaurateur and commentator. As the co-founder of New Albany’s Sportstime Pizza/Rich O’s Public House (which later became New Albanian Brewing Company) in the 1990s and early 2000s, Baylor played a seminal role in Louisville’s craft beer renaissance. Currently he is the beer director at Pints&union in New Albany and Common Haus Hall in Jeffersonville. Baylor’s “Hip Hops” columns on beer-related subjects have been a fixture in F&D since 2005, and he was named the magazine’s digital editor in 2019.