Last week’s journey through time to the 1850s left me somewhat antebellum-lagged, and so this week a recuperative rerun seems merited.

—

Why Saison Dupont remains the Belgian-style country ale yardstick

My grandparents inhabited farmhouses, primarily because they owned farms and lived right where they worked. There is no evidence to indicate any of them homebrewed or drank beer in appreciable quantity, although a few bottles of bourbon, kept stashed strictly for “medicinal” purposes, is a virtual certainty.

Lately “farmhouse” has come into fashion as a beer style descriptor, and fevered scrutiny has greeted this usage, to the degree that many beer aficionados spend less time drinking “farmhouse” brews than arguing about terminology and posting brewfies to Instagram.

Some enthusiasts believe farmhouse brewing can occur only when organic retro-engineered barley, hand-harvested hops and wild yeasts are deployed for a brew day in an actual house on a real farm, although in a pinch, the barn also might do. (Mercifully, the outhouse has yet to be mentioned as an attribute of authenticity.)

(Originally published in the Winter 2019 issue of Food & Dining)

Defining stylistic terms is difficult under these circumstances. Should farmhouse ales be dry, malty, sour, bitter, rustic, refined, seasonable or strong? In fact, all of these characteristics can apply depending on a brewer’s whim.

While there seems to be general agreement that Belgium is the heartland of farmhouse ales, even this assertion isn’t clear, given that Swedes, Finns and Estonians have their own distinct indigenous narratives. What’s more, our Euro-bias is obvious; what about sorghum beers from Africa and corn-based chicha in South America?

Must farmhouse beers be warm-fermented ale at all, seeing as there are traditions of cool-fermented farmhouse lager brewing in Bavaria and Northern France?

The current ruckus over “farmhouse” is a topic of sufficient intensity that a lapsed brewery owner like me is better to focus on a narrower bit of the kaleidoscope: saison, which has survived modernity and remains an exemplar of traditional European countryside taste in ale.

The story begins with geography. Saison is the French word for season, brewed by farmers in Wallonia, the French-speaking southern half of Belgium bordering on France, Luxembourg and Germany. Flanders is the country’s northern half, where the language is Flemish, a Dutch dialect.

The mysterious forested hills and ridges known as the Ardennes are situated in southeastern Wallonia, an enduringly scenic and sparsely populated area that was the setting for the Battle of the Bulge in World War II. As one travels west and north, the hills become gentler. The Meuse and Sambre River valleys link Liege, Namur, Charleroi and Mons, cities once renowned as industrial centers of coal, steel, glass and cement production. By the 1960s, many of the factories were obsolete, and a “rust belt” formed.

Mons, a battleground in World War I, is the capital of Hainaut province, the westernmost in Wallonia. Beginning in Mons, and continuing westward to Tournai, the terrain begins to flatten into the Flanders plain stretching to the Atlantic.

Crops in Hainaut include wheat, oats, sugar beets, chicory – and barley. A simple bike ride through the countryside yields abundant olfactory evidence of hogs and cattle. It’s common even today to see four-sided brick farmsteads, with the house and outbuildings arranged around a central courtyard.

For hundreds of years, Wallonian farmers situated their rudimentary kettles and fermenters near deeply dug wells, golden fields of barley and trellises heavy with hops. They brewed only during the cool months, bottled and cellared their output, because in the time before refrigeration it was too warm to make beer in summer.

The milder versions of these ales were intended as refreshment during the working day, with the stronger ones (higher in alcohol, more residual sugar and calories) reserved for sustenance later in the evening. There were as many different variants as farmhouse breweries, although similarities in ingredients probably yielded an approximate regional template.

The industrial revolution came full-throttle to Wallonia in the 19th century, and ripple effects were pervasive. Mechanized agriculture required fewer workers, who migrated to urban areas. Modern breweries sprang up to serve them, and many emulated German lager brewing, the great trend of the 19th century.

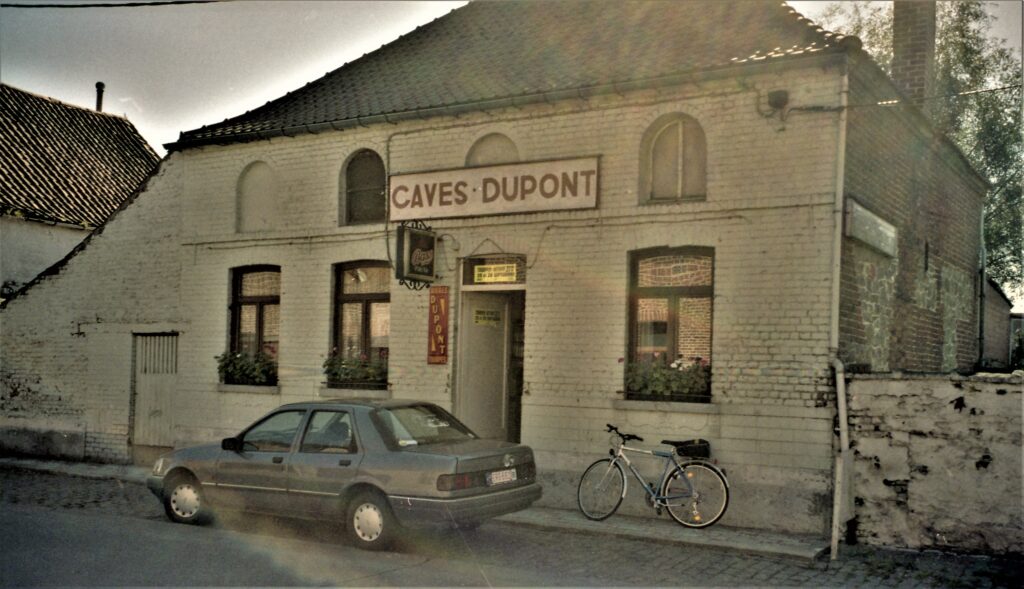

Time passed, tastes changed, and in Hainaut province, where hundreds of breweries once flourished, only a handful eventually survived to serve small local markets. One of them was Brasserie Dupont, then as now one component of a family-owned farm.

In the early 1980s, Don Feinberg and Wendy Littlefield founded Vanberg & DeWulf, a specialty beer importer. They contacted Brasserie Dupont as a possible supplier, and the brewery couldn’t imagine why; really, rustic ale in America?

Eventually Dupont agreed to export its Vieille Provision (today’s Saison Dupont) to America, explaining why one particular saison of many, as interpreted by a rural brewery in the fields near Tourpes, became the saison yardstick for generations of craft brewers. So it remains, at least in my personal estimation. Rick Stidham, owner and brewer at Louisville’s Akasha Brewing Company, agrees.

“Saison Dupont is the classic example of the style,” Stidham told me by email. “It’s kind of a beacon for dead-center that any brewer would do well to keep sight of while developing a new saison, although for me exploring some distance from dead-center is almost always more fun than trying to hit it.”

Consequently, if the center of the target is Saison Dupont’s recipe, then it’s a disarmingly simple one: 100% pilsner malt, two hop additions, local hard water and the secret weapon, a proprietary yeast strain that produces a fruity, peppery spiciness and a lean, attenuated body. More than one brewer has referred to this yeast as Dupont’s secret weapon.

Golden-colored, dry and peppery with a trademark rocky head of foam, Dupont emphatically agrees with grilled meats, funky cheeses and seafood. Other commercially brewed saisons worth sampling are Fantome (Belgium); Boulevard Tank 7 and North Coast Le Merle (American craft beers); and Monnik Beer Company’s local Eagle Skull.

Meanwhile breweries like Akasha are expanding style parameters, giving new meaning to saisons and farmhouse ales alike. I asked Stidham for an example.

“At Akasha, we haven’t used Saison Dupont as a template so much as an inspiration. Our recent Brettanomyces saison, Alto, has a similar dryness and shares other less-well-definable characteristics, but obviously it’s not at all the same beer and wasn’t intended to be.”

Nor should it. In our current cornucopia of beer choice, tradition and innovation are by no means mutually exclusive, and the search for your perfect beer can last a lifetime. F&D

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 41 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.

Roger Baylor is an entrepreneur, educator, and innovator with 41 years of beer business experience in metropolitan Louisville as a bartender, package store clerk, brewery owner, restaurateur, writer, traveler, polemicist, homebrewing club founder, tour operator and all-purpose contrarian.