In 1749 the pseudonymous French cookbook author known as Menon published a work called La Science Du Maître D’Hôtel Cuisinier (roughly, The Skills of the Steward Chef). In it, Menon documents a form of culinary art that dates back to at least the Renaiassance: the use of elaborate table centerpieces to teach a moral message.

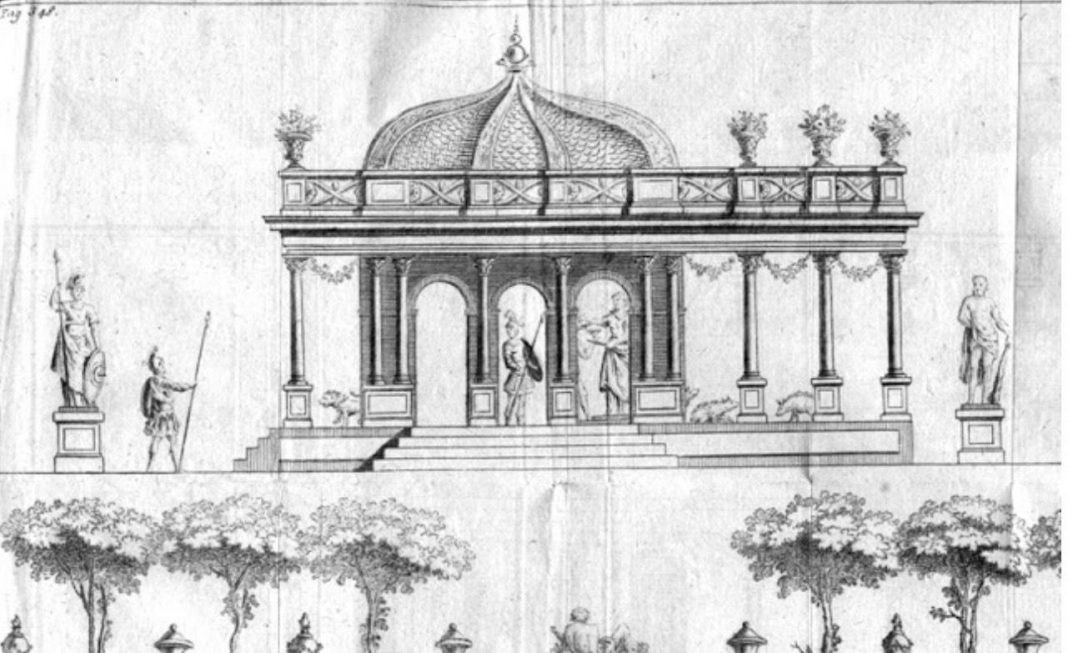

In this case, Menon’s subject is the mythical sorceress Circe, and the episode in the Odyssey where she captures Odysseus and magically transforms his crew members into swine. The elaborate sculpture – made of sugar – is intended as a cautionary tale about greed, which is just the sort of ironic device a privileged diner might have relished during the decades before Marie Antoinette suggested cake as a dietary replacement for bread.

Food and foodways have always been about more than nutrition. From the beginning of recorded history and literature, it’s been clear that food has defined notions of personal and national virtue or vice. It has always defined power and status by the way calories are apportioned across a population. And foodways have always been a marker of social class and rank. In the early days, using a fork instead of your fingers was a marker of civilization. In our time, one’s status as a “foodie” (a loathsome word if ever there was one) has long correlated with one’s life-list of dishes and cuisines. And for many of us, there is a notion that character is defined by one’s commitment to farm-to-table cuisine; one’s choice of a plant-based or omnivorous diets; and even one’s knowledge of and choices of beverage.

One of the profound consequences of the coronavirus lockdowns has been the disruption of that part of the social order. After all, assuming that you are not one of the economically vulnerable people for whom food security has become a life-threatening crisis (and though those people may not be visible on social media, their numbers are legion), conspicuous consumption isn’t quite the same when you’re eating carry-out or delivery food.

It’s easy to mock those culinary social markers. And there is no question that they are trivial compared to addressing the inequitable distribution of calories across the population.

But it seems to me that in a civil society, those social markers are also vitally important. Coming together to dine is one of the foundations of a civilized society. All of human society begins with the simplest act of hospitality: sharing food with one another.

Over the last quarter century, Americans experienced arguably the most radical change in food and dining in the history of the nation – and perhaps since 1500, when voyages of exploration started redistributing vegetables, fruits, and grains – potatoes, tomatoes, and coffee, for instance – across vast oceans to new continents.

We are already seeing hostile divisions in the social fabric as some of us go mask-free into crowded bars, and mock the stay-at-homes, while others of us stay at home and gasp at photos and videos of feckless behavior.

It’s early days, of course. But it is inevitable that what we are experiencing now will have an enduring effect not only the economics of the food business, but on the ways we experience food. Some of that is inevitably happening now, as home cooking explodes.

But it has always been the case that creative chefs have responded to changes in the world around them with new approaches to cookery and presentation. Right now, most of their efforts have been focused on the urgent need to figure out safe preparation, packaging, and delivery techniques. But as diners return to the dining rooms, I can’t help wondering what “masked” cuisine will look like.

—

Marty Rosen, Food & Dining Magazine’s Editor-in-Chief, has been covering food, dining, performing arts, and culture in Louisville for a quarter-century, and has been a contributor to F&D since the first issue. Marty served as dining critic for LEO Weekly (2003—2006) and The Courier-Journal (2006-2014). In addition, he has written for Louisville Magazine, the Kentucky Department of Tourism, The Voice-Tribune, and other publications.