In 1931, Louisville native Louis D. Brandeis was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States when a case known as New State Ice Co. v Liebmann appeared on the docket.

The case involved a commercial dispute. A company called New State Ice had a license to sell ice in the state of Oklahoma, and was happily cubing up a storm.

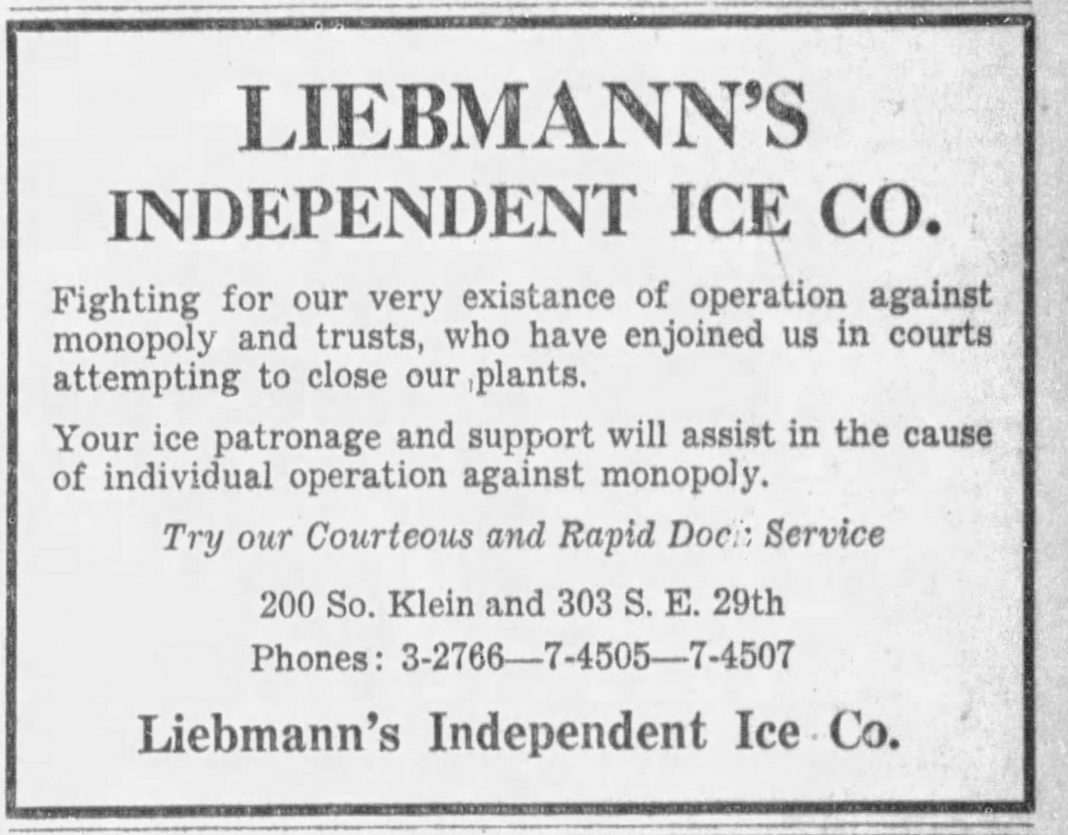

Then along cometh another iceman, a fellow named Paul Liebmann. The state declined to give him a license, but nevertheless he opened a new, modern, state-of-the-art ice plant in Oklahoma City.

And then he opened a second one.

By 1931 Liebmann’s plants were producing 160 tons of ice a day.

Remember, we’re talking Oklahoma in the 1930s. These were Dust Bowl times, and ice was the iPhone of the era. In Oklahoma, ice was an essential commodity and state law regulated its manufacture and required anybody who wanted to get into the business to prove that there was demand for an increased supply of ice.

New State’s license gave them a pretty strong hold on the market, and they didn’t want to relinquish it. So they sued.

And they lost.

Liebmann won. And Liebmann, alas, died a year later at the age of 47.

By all accounts, Louis Brandeis is one of the most influential lawyers and Justices in American legal history. (The University of Louisville Law School is named after him, and his remains and those of his wife Alice Goldmark Brandeis are buried under the Law School portico.)

The Court’s majority ruled that Oklahoma’s licensing requirement was an unconstitutional impediment to free enterprise and competition.

But Brandeis disagreed with the majority and wrote a dissent. The thing about Brandeis is that even when he was on the losing side his opinions were elegant and thoughtful. In this case, he wrote in defense of Oklahoma’s power to regulate commerce because he deemed it an essential feature of American-style Federalism.

Here’s what Brandeis wrote: “It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.”

This “laboratory” metaphor has never seemed more potent and applicable.

Apart from the microscope, the most iconic symbol of the modern laboratory has to be the Petri dish. It was invented by in the 1870s by a German bacteriologist named Julius Richard Petri.

The Petri dish is used for culturing microorganisms, and it’s hard to imagine modern science without it. You may remember that Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin – the antibiotic that changed world history – when a bit of mold contaminated a Petri dish of bacteria and killed the stuff Fleming was studying.

What’s happening now is that the various states, and nations, and businesses have become Petri dishes in a global social, medical, and economic experiment to determine how best to address the Covid-19 epidemic.

It’s a risky experiment, but lots of people are eager to take part. Other are very eager to mitigate their risk factors.

There are lots of ways to mitigate risk. For an individual, the best strategies are clear: social distancing, wearing a mask, washing your hands, etc.

Some businesses – including restaurants – are mitigating the risks to their staff members and customers by rigorously following the above protocols in preparing food and restricting service to delivery, pick-up, and curbside.

Other businesses are looking to the government for help in mitigating their risk. At the Federal level, Kentucky Senator Mitch McConnell is planning legislation to protect businesses from lawsuits if workers or customers assert that unsafe practices caused them to become infected. So there is certainly safety in that, at least for the businesses.

You can pick your side in this dispute.

But here’s the thing about Petri dishes: the microorganisms in the experiments don’t have a choice.

We do.

As a customer, staff member, or business owner, you have a choice.

—

Marty Rosen, Food & Dining Magazine’s Editor-in-Chief, has been covering food, dining, performing arts, and culture in Louisville for a quarter-century, and has been a contributor to F&D since the first issue. Marty served as dining critic for LEO Weekly (2003—2006) and The Courier-Journal (2006-2014). In addition, he has written for Louisville Magazine, the Kentucky Department of Tourism, The Voice-Tribune, and other publications.