Master distillers’ decades-long experience lays foundation for Bourbon industry’s future.

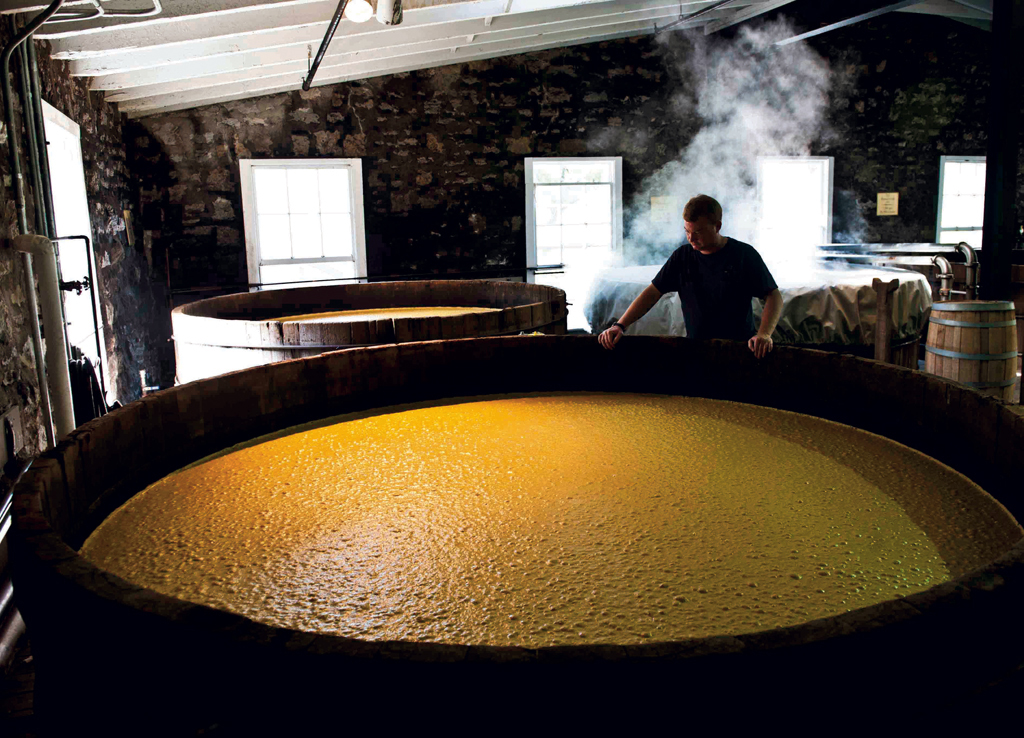

Making good Bourbon takes a long time. So does making a master distiller. These artisans of alcohol must learn every aspect of the Bourbon business, and once they rise to the top, they tend to stay there — often for decades.

In recent years, however, some new names have joined venerable veterans in the lineup, and others will soon follow. For one of Kentucky’s signature industries, this is a rare time of transition.

When Four Roses Master Distiller Jim Rutledge decided last year that he would retire after nearly 50 years in the business, Brent Elliott, operations manager at the Lawrenceburg distillery, was as surprised as anyone. But if Elliott thought the retirement announcement was a bombshell, he was dumbstruck by what his bosses at Four Roses said next: “And you will be the next master distiller.”

Although Elliott had worked at Four Roses since 2005, he had no immediate designs on the top job, he said. “I never let myself consider it. I never thought Jim would retire! I didn’t allow myself that kind of thinking.”

One could be forgiven for thinking that master distillers in general never retire; they just “mature.” Those at Kentucky’s large distilleries mark their tenure not only in years, but in decades. Wild Turkey’s Jimmy Russell celebrated six decades in the Bourbon business in 2014, for example. Chris Morris has worked at Brown-Forman for four decades; Fred Noe has been with Jim Beam for three decades and change.

Inevitably, however, the Bourbon baton is being passed to the next generation. In addition to Elliott’s promotion at Four Roses, the past five or so years have seen transitions at Heaven Hill, Wild Turkey and Maker’s Mark, and future master distillers are being identified and groomed across the industry—not to mention the new crop of distillers that has sprung up with the craft distillery movement.

“Obviously, everything moves forward and changes,” Elliott said. “But it’s still a bit strange to think of the Bourbon landscape in 10, 15 years without your Jim Rutledges, your Jimmy Russells—they’re such the cornerstone and identity of the industry and of Bourbon. But it’s exciting, too. It’s meeting new people and seeing what other new distillers have to offer. I think what is important is that the legacy and the tradition and the pride of product are carried on. And whether it’s someone in the company, or from outside, I think that is probably the criteria for someone to be handed the torch.”

Becoming “part of the story”

Of course, the Bourbon business in Kentucky has seen plenty of personnel changes in its 200-year history. But until relatively recently, consumers were focused solely on the liquid in the bottle, not on the person (or people) who had put it there.

“When I started at Brown-Forman 40 years ago, Bourbon wasn’t cool,” said Chris Morris, master distiller for the company’s Bourbon brands, including Woodford Reserve, and chairman of the board of the Kentucky Distillers’ Association, a trade group. “There was no activity in terms of excitement, no new brands… So if the industry was boring, and the brands were boring, who cared who made it?”

The recent Bourbon boom, which has increased customer interest along with the number of distilleries and brands, has changed that.

“We have gone the way of the great winemakers,” Morris said. “Who made that wine, what is their house style and their individual influence—those are the kinds of things consumers now want to know about their whiskey as well. The master distiller has become part of the story.”

But what is a master distiller? The title, which has been in use for only about 20 years, was created by marketers—“head distiller” or just “distiller” once served the purpose—and as yet carries no uniform definition or official requirements.

“When the subject of master distillers came up with new craft members [of the KDA], we [Brown-Forman] led the discussion that who and what a master distiller is should be an individual company decision, because each of the heritage members [large distilleries] have their own standards,” Morris said. “No one should have the rules dictated to them.”

The path to master distiller at Brown-Forman is quite regimented, with required training, education, longevity and seniority all taken into account, Morris said. Unlike some Kentucky distilleries, where the job has passed from father to son, “Brown-Forman has never had a history of hereditary transition in that position,” he said. “It’s been based on a meritocracy, but a lot of that merit comes from being in that position and learning.”

Morris, for example, started his career with Brown-Forman as an intern during high school and worked his way up, spending time at the company’s Jack Daniels distillery in Tennessee and in its tequila distilleries in Mexico along the way. He learned the art of Bourbon from longtime Master Distiller Lincoln Henderson, who created Woodford Reserve, and succeeded him when Henderson retired from Brown-Forman in 2004. (Henderson then collaborated with his son, Wes Henderson, to create Angel’s Envy, for which Wes’ son, Kyle, now serves as production manager. Lincoln Henderson passed away in 2013.)

Brown-Forman conducts annual succession planning and talent reviews, assessing how the company can best bring along promising master distiller candidates, Morris said. He couldn’t divulge any names, and he doesn’t plan to go anywhere anytime soon, so it may be a while—perhaps a long while—before we hear about them.

Four Roses

Brent Elliott considers himself very fortunate. He worked at Four Roses for only 11 years before being named master distiller. “Some people wait 20, 30, 40 years,” he said. In fact, until the early 2000s, he had never even imagined a job in distilling. After growing up in Kentucky and graduating from UK with a degree in chemistry, he was working as an analytical chemist in Tennessee.

“I’ve always had a respect and appreciation for Bourbon, but also sort of a sense of wonderment,” he said. “It seemed like kind of a magical industry that I never really imagined people got hired into. Either you were in it, or you weren’t.”

Then one weekend in 2005, he and his wife toured Woodford Reserve for fun. “I thought, ‘You know, they probably employ chemists,’ and something clicked.” The next day, he checked online and found a job posting for an assistant manager of quality control at Four Roses. “I had the perfect skill set—the exact experience to set up an analytical lab.”

Initially, he spent about 75 percent of his time in the lab. Within a year, as the company added people, that dropped to 25 percent, with the remainder split between general quality control and sensory evaluation of the liquid—mingling, blending and the like. Eventually, Elliott became deeply involved in the quality of everything from the incoming grains to the outgoing finished product. The first Four Roses product with his name on it—Elliott’s Select Limited Edition Single Barrel—was released in June. “I’d never really thought that I could mix chemistry with something I am passionate about,” he said. “This has been the perfect scenario.” (Jim Rutledge’s retirement didn’t last long, incidentally; he and business partners are currently raising funds for the J.W. Rutledge Distillery, which they plan to build in Louisville.)

Heaven Hill

You might imagine that at the distilleries that do have a “hereditary transition,” as Morris calls it, the path to the top is easier. You would be wrong. Before assuming the title of master distiller from his father, a son must prove himself in every aspect of the process, starting from the bottom.

At Heaven Hill, for instance, one of Craig Beam’s first tasks was cleaning up years’ worth of pigeon droppings in one of the company’s warehouses in Deatsville, Kentucky. Craig learned the trade from his father, Parker Beam, who had worked alongside his father, Earl Beam, before inheriting the title of master distiller in 1975.

Eventually, Parker and Craig Beam became co-master distillers of Heaven Hill, which has another family connection: Run by the Shapira family since the 1930s, it is the largest family owned and operated distilled spirits company in the country. After Parker stepped down in 2014 following a diagnosis of ALS, Heaven Hill promoted Denny Potter, manager of its Bernheim Distillery in Shively, to be co-master distiller with Craig.

In downtown Louisville, meanwhile, Heaven Hill operates a micro-distillery that produces one barrel per day in its Evan Williams Bourbon Experience, which opened in 2013 along Whiskey Row on Main Street. The master distiller at this tourism destination, Charlie Downs, isn’t part of the family, but he might as well be: He has worked for Heaven Hill for 39 years.

“I am one of the few people in our company that has worked with all three generations of our master distillers, and also all three generations of our owners,” Downs said. “Earl Beam, Parker, then Craig; and then in the Shapira family, Mr. Ed, then Max and then Max’s kids.

“I tell people that I guess they felt sorry for me,” he said with a wink. “They took me under their wing and said, ‘We’ll actually teach him the trade without him knowing it.’”

Wild Turkey

Jimmy Russell tells a similar story about his start at Wild Turkey in 1954. In his first years, as he worked under Bill Hughes, the distillery’s second master distiller, and Ernest W. Ripy Jr., the great-nephew of distillery founder James Ripy and Wild Turkey’s third master distiller, he was moved from one part of the Bourbon-making process to the next. “I thought they was trying to get rid of me,” he jokes, “but they was teaching me the whole thing.”

He, in turn, taught the whole thing to his son, Eddie Russell, who has been working at Wild Turkey for “only” 35 years and began with exciting jobs like mowing grass. If anything, Jimmy says, he worked Eddie harder than anyone else so that he couldn’t be accused of favoritism. The two have been co-master distillers since early 2015. While Eddie says that he thought his name was “No” for years because that was the response he always got from Jimmy when he suggested something new, he has now released three limited-edition Bourbons, most recently Wild Turkey “Master’s Keep.” Keeping the Bourbon line flowing, Eddie’s oldest son, Bruce, is now a brand ambassador for Wild Turkey’s Russell’s Reserve. Eddie created Russell’s Reserve in 1998 to mark Jimmy’s 45th year in the business, and his then-anticipated retirement. As if.

Maker’s Mark

In 2010, Rob Samuels became the eighth generation to lead another storied Bourbon family: Maker’s Mark. The Samuels family has been in the whiskey business since 1840. Rob’s grandparents, Bill and Margie Samuels, developed Maker’s Mark, a smoother, sweeter Bourbon, in the 1950s. Through inspired marketing efforts, Rob’s father, Bill Samuels Jr., elevated Maker’s Mark from a regional brand to a worldwide one. As the new chief operating officer and general manager of the Maker’s Mark Distillery in tiny Loretto, Ky., Rob Samuels will build on that reputation and on the tremendous popularity of the idyllic, Victorian-inspired distillery as a tourist destination.

Overseeing production is Master Distiller Greg Davis, who has been with Maker’s Mark for six years. Although he’s been in the industry for 26 years, and a master distiller for 16 of those, the nickname that another industry veteran playfully gave him tells you all you need to know about longevity in the Bourbon business: “The Baby.”

Jim Beam

Frederick Booker “Fred” Noe III, current master distiller at Jim Beam, grew up with Eddie Russell in the Bourbon business. His father, the late Booker Noe, was a contemporary and close friend of Jimmy Russell. The two older men were so alike, Fred Noe says, that “if you had put both of them in a bag and pulled one out, you wouldn’t know which one you had ahold of.”

Booker and Fred Noe represent the sixth and seventh generations, respectively, of a Bourbon dynasty that stretches back to Jacob Beam, who sold his first barrel in 1795. Booker Noe, who worked at the Jim Beam distilleries in Boston and Clermont for nearly 50 years, revitalized the Bourbon industry in 1988 when he released Booker’s, a barrel-strength Bourbon that helped to create the “premium” category. Booker Noe passed away in 2004, and Fred Noe succeeded him. In his time as master distiller, Fred has introduced his own innovations, such as the Jim Beam Signature Craft Series.

On May 2, 2016, he and his son, Freddie Noe IV, the eighth generation of this Bourbon-making family, filled the 14 millionth barrel of Jim Beam. Freddie, who has worked in various areas at Beam for four years, is most intrigued by distilling, Fred Noe told Bloomberg Businessweek. No surprises there.

Buffalo Trace/Barton 1792

Another Kentucky distillery is in the midst of transition with the retirement in May of Ken Pierce, master distiller at Barton 1792 Distillery in Bardstown, which, like Buffalo Trace Distillery in Frankfort, is owned by Sazerac Brands.

Pierce, who had spent more than 30 years in the industry, oversaw production of brands such as Very Old Barton and was instrumental in developing the recent 1792 Small Batch line of Bourbon. He also served as an adviser on industrywide projects, such as the George Washington Distillery project, in which historically accurate equipment was used to distill rye whiskey at Mount Vernon in Virginia, much as the first president would have done.

As of press time, a successor had not been named. “We do take succession planning very seriously at both Buffalo Trace and Barton 1792 Distilleries, especially given the importance of the role of the master distiller,” spokeswoman Amy Preske said. “At both distilleries, we have been strengthening the breadth and depth of talent that we have on the team.”

Buffalo Trace Master Distiller Harlen Wheatley, who has worked at the Frankfort distillery for more than 20 years, has no plans to go anywhere. In fact, he already knows which products the distillery will be making through the year 2039. Now, that’s some long-term planning.

Castle & Key

One up-and-coming distiller who has garnered quite a bit of media attention is Marianne Barnes, Kentucky’s first female master distiller since Prohibition. After graduating from the University of Louisville with a degree in chemical engineering, she was hired by Brown-Forman, where she studied under Chris Morris.

But in 2015, she was lured away to help build a new distillery—now called Castle & Key—on the grounds of the historic Old Taylor Distillery just outside of Frankfort. The distillery was built in 1887 by Col. E.H. Taylor to resemble a castle, with grand buildings and public spaces, but has been vacant since 1972. While major restoration continues, Barnes is working on a gin using botanicals from a garden planted by noted landscape architect Jon Carloftis of Lexington.

For Barnes, leaving the venerable Brown-Forman wasn’t something she had planned. But in an industry where master distillers often work into their 70s and 80s, the chance was too good to pass up for someone in her 20s. “This was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” F&D