[Originally published in the F&D Fall 2015 issue]

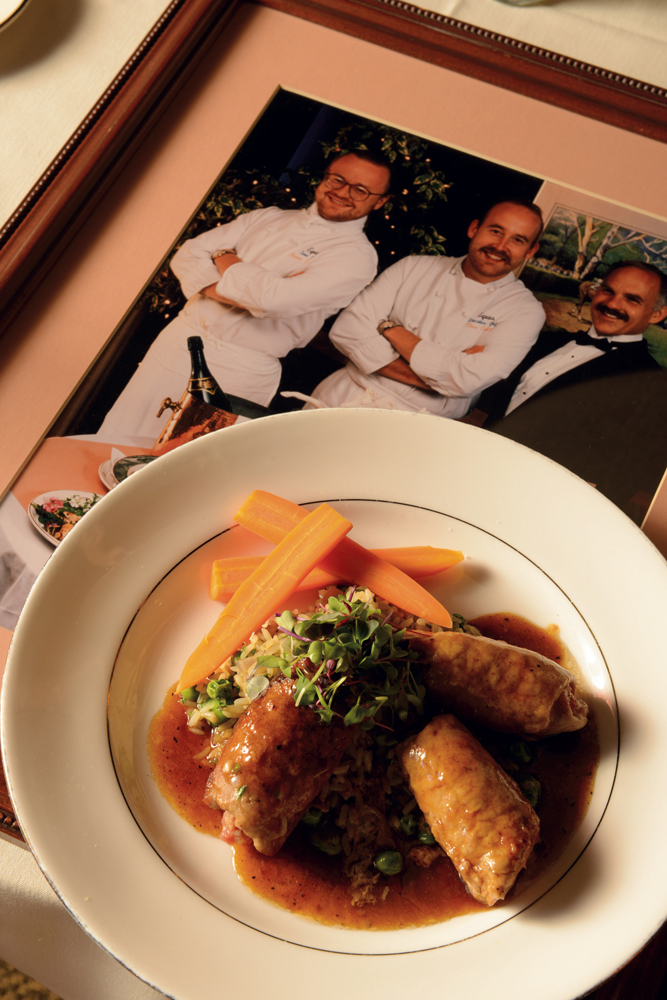

After 30 years, Equus and its owner-chef Dean Corbett are still cooking for fans in St. Matthews

In August, Equus reached a milestone few restaurants in Louisville’s history have achieved: 30 years in operation.

Chef-owner Dean Corbett ruminated on the thought for a moment before mumbling almost wearily, “Hard to believe.” Then he shook his head, paused and let a satisfied grin spread over his face. “It really is hard to believe.”

Three decades is a remarkable achievement in any industry, much less in the restaurant business, where establishments open and close so quickly their lifespans should be calculated in dog years. Such math would make Equus a veritable Methuselah among its fine-dining peers, only a few of which can compare. (Jack Fry’s and Vincenzo’s are 29, and Lilly’s is 28.)

Some days Corbett admits to feeling like Methuselah. His back and feet ache constantly despite major surgery to repair both. If his body had an odometer, his Kelly Blue Book value would be junk.

“But the back surgery made me almost an inch taller,“ he said when we visited two years ago after the surgery. “I was that stooped over!“

And yet his 53-year-old engine rarely idles. He’s always thinking about the next tweak to his businesses, which also include Jack’s Lounge and Corbett’s: An American Place. He can’t walk through his dining room without being greeted by a longtime customer.

“Those people, customers who’ve been with us since we started, they’re why we’re here,” Corbett said. “They’ve supported us through thick and thin. Many are quite old and can’t come as often, but now their grandchildren are coming here.”

Corbett was just 23 when his father, Jack Corbett, invested $25,000 to buy a share of Equus from owner Rodulfo Pantoja in 1985. Pantoja and his family were successful real estate developers, but they struggled as restaurateurs, and their horse-themed eatery was an odds-on favorite to scratch if it didn’t source experienced guidance quickly. After a few months in business, they approached Corbett about becoming its chef, but in that first meeting, he demurred and pointed to his lack of management experience.

“I’d just been made sous chef at Sixth Avenue, so I just didn’t think I was ready,” Corbett recalled. “But a few months later, things got worse at Equus. They really needed help, and so they came back to me.”

Eager for the challenge, Jack Corbett convinced his son to take ownership together.

“We definitely took this on with fear and trembling; neither of us were all that confident,” Corbett said. “I took on all the cooking duties and hiring people, and my dad took care of

paying all the bills and management and marketing — things I had no clue how to do.”

No small wager on Equus

Equus was in debt and losing money, leaving the Corbetts to cut its unprofitable lunch service and refine its dinner menu. Dean implemented policies and procedures learned during his two years working at Sixth Avenue and its sister restaurant, the venerable Casa Grisanti. Dominic Serratore, then Casa’s executive chef and Corbett’s boss, said his young charge was an exceptionally quick learner who was good in the clutch.

“He also had energy on his side, and he was very ambitious,” said Serratore, now chef and co-owner of Ditto’s Grill. “I was like most everyone, thinking, ‘He’s a little young, but it’s a great opportunity.’ And he showed he could handle it by applying everything he’d learned in our operations.”

Within two years, Equus’s sales had doubled and expenses were down by 50 percent.

“But we were still only breaking even!” Corbett said. “It was a big hole to dig out of.”

The Corbetts then bought a majority share in the business and made more changes.

“That move gave us more of a voice in the decision-making,” he said. “And the restaurant just continued to get better.”

“I just couldn’t believe it, and I have to admit that I cried,” Corbett said. “It was the proudest moment of my life to that point.”

Lounge of Luxury

For months afterward, business at the 60-seat restaurant quadrupled, leaving the men no choice but to execute the first of what would become several expansions of the dining room and kitchen. The largest came in 2000, when Corbett opened Jack’s Lounge, named in honor of his father, who died in 1999.

“We’d always wanted a bar, but a classy one, a true martini bar, where people could lounge, smoke and just relax,” Corbett said. “It was tremendously popular from the start.”

Even despite its opening night struggles.

“We opened the doors to a place with no freakin’ furniture – I’m serious!“ he said. “But people wanted to come in, so we let them in.”

When the furniture truck arrived, Corbett recruited partygoers to bring it in.

“I gave everyone who was sober — and there weren’t many — a pair of scissors or a knife and said, ‘Let‘s go get the furniture and move it in here,’” he said.

Originally, customers entered Equus from the building’s left side and Jack’s through its center. But after a decade of explaining to frustrated patrons that the next-door businesses weren’t connected by a doorway, Corbett hired a firm to make the facilities one by cutting a hole through the 18-inch-thick firewall.

“It took 27 hours to do that,” he said. “Rodulfo had built us a hell of a building.”

For almost a quarter century, Equus had been a white tablecloth restaurant, but connecting it to the more casual Jack’s Lounge helped Corbett see it was time to soften the formal edges of the old standard.

“That and the recession, which cut spending on fine dining,” he said. “People really started spending less in that stretch.”

Kathy Cary, chef and owner of Lilly’s Bistro, made similar changes to her restaurant in 2002. Looking back, she said she regrets waiting so long.

“Making our place relaxed was one of the smartest things I’ve ever done, and I know it worked for Dean, too,” she said. “Our customers loved the change … and it’s gone a long way to drawing in younger crowds.”

Not everyone accepted the more casual Equus, Corbett said, but “at least by then we had opened Corbett’s, so they could get their fine-dining experience there. Overall, it was a great change I probably should have made earlier.”

Longtime Equus fan Thomas Clay said he’s seen Equus adjust multiple times to new trends, and on each occasion, those transitions were seamless. The Louisville attorney said Corbett was wise to merely tinker over time with Equus without overhauling its personality.

“(Dean) has maintained some signature dishes which he created during the Equus run — Shrimp Jenkins and the mushroom fumé, to mention only two — (but) he’s not constrained by the past,” said Clay. “He’s also totally hands on when it comes to his enterprises … a people person who inspires great loyalty from his staff members.”

Jim Cover, Equus’ maître d’ for 27 years, agreed, calling Corbett “one of the best people in the world to work for, someone who actually cares about his staff. If they have problems, he’ll personally go out of his way to assist them.”

Cover said Equus’ success was born of Dean’s and Jack’s desire to please customers, and that sentiment was shared by their staff.

“Equus has always had a team that wanted to make customers happy,” said Cover, who is now retired. “That’s what it’s had going for it: People who are willing to adapt to customers’ needs.”

Despite leading Equus for 30 years, Corbett admits that running even a busy, profitable business is harder than ever. Restaurant margins have shrunk drastically since 1985 as food and labor costs have soared.

“I’m making far less money now, yet we’re generating much more in sales,” he said. For example, Equus’ legendary Shrimp Jenkins cost $7.50 in 1985; it now costs $24. “Food costs are just out of control these days, and customers don’t always understand why prices have to go up.”

Customer desires also are more fluid than ever, he added, saying younger diners want smaller portions and more menu variety. Plus they expect high standards at the bar.

“They want lots of good bourbon, and it better be at least a 2-ounce pour,” Corbett said. Under the guidance of veteran bartender Joy Perrine, an employee for 29 years, Jack’s cocktail program expanded dramatically. “That’s especially happened because of the younger crowd that’s looking for great drinks.”

Serratore applauds his former charge’s ability to adapt to changing trends, saying inflexibility to customers’ changing desires kills restaurants one quarter Equus’ age.

“Dean has developed his own style, and as things have changed, he’s grown tremendously as a result,” said Serratore, whose own restaurant turned 25 this year. Equus and Jack’s Lounge “have the right amount of sophistication, and that implies to customers that they’ll be taken care of. It hits a certain chord that applies to a niche demographic that supports the business to no end.”

Indeed it does. Every Monday through Saturday, cars begin filling the lot at 4 p.m., when Jack’s opens. If patrons can’t get a cushy lounge seat at Jack’s, they’ll either stand or slide back to Equus‘ bar when it opens at 5. The drinks are just as good there, and the setting is quieter.

“And you can get the whole menu no matter which place you’re in,” Corbett said, adding that it wasn’t always that way. “I figured, why not? They’re here, the food’s back there, so let ‘em have what they want.”

That’s a mandate heard constantly by a slew of talented chefs who matriculated at Equus before moving on to other restaurants. Just a sampling of its culinary alumni still cooking in Louisville include Dallas McGarity (Marketplace Restaurant at Theater Square), Tavis Rockwell (LouVino), Nick Sullivan (610 Magnolia) and Finbar Kinsella (Lilly’s Bistro and later, St. Joseph’s Orphanage).

Cary said Corbett’s passion for cooking attracts talented chefs whom he inspires to grow and move elsewhere, just as he did. She said he’s also a de facto leader among the city’s independent restaurant chefs.

“He’s the connector among us, kind of the glue that holds us chefs together – the old ones especially,” Cary said.

Corbett said he owes aspiring chefs the same mentorship he received from Serratore and many others. That means he’s constantly teaching newcomers at Equus.

“Maybe the hardest part of the job is the most important, and that’s to go back and train these guys to do the basics right, the dishes that our longtime customers love the most,” Corbett said, adding that classics like his crab cakes require constant retraining. “When you have customers joking that the mushroom fumé has healing powers, you know it’s got to be right. Our customers have been coming here a long time, and you can’t fool them.” F&D